Dear Reader,

History reveals itself everywhere: it’s as old as the world, with an immeasurable future to come. Over time we find that even everyday things have earned the right to a closer look.

My recent visit to a fourteenth-century castle has had me wondering whether instances of vandalism might represent our social history of the future.

Let’s talk about graffiti (or, in the singular, graffito).

Graffito

(ɡrəˈfiːtəʊ)

Singular noun

DEFINITION: See graffiti

Thanks, Collins English Dictionary. 🙄

More helpfully:

Graffiti, in British English

(ɡræˈfiːtiː)

Plural noun

Word forms: singular -to (-təʊ)

1. (sometimes with singular verb)

Drawings, messages, etc, often obscene, scribbled on the walls of public lavatories, advertising posters, etc2. archaeology

Inscriptions or drawings scratched or carved onto a surface, esp rock or pottery

People have been literally making their mark on structures in their environment for millennia. Where in the distant past rocks and cave walls were the canvas, as our surroundings developed to become more diverse, so too did the graffitists’ substrate, with bricks, stone pillars, subway trains and motorway bridges all taking their turn as subjects for their attention.

I’m not talking about art here – those spraypainted spaces of self-expression that are ubiquitous in our towns and cities – but about what we as children used to call the ‘I woz ‘eres’.

Adding words to the landscape – setting ourselves in stone to leave proof of life for posterity – is not something I choose to do for myself, no. But I nevertheless take pleasure in seeing these dubious gifts from those who have gone before – if only to take the opportunity to engage with their world.

Scouting around the walls inside the castle I found examples of the following:

Declarations of love

Self-expression in different languages and scripts

Names and dates

Graffiti made in memoriam

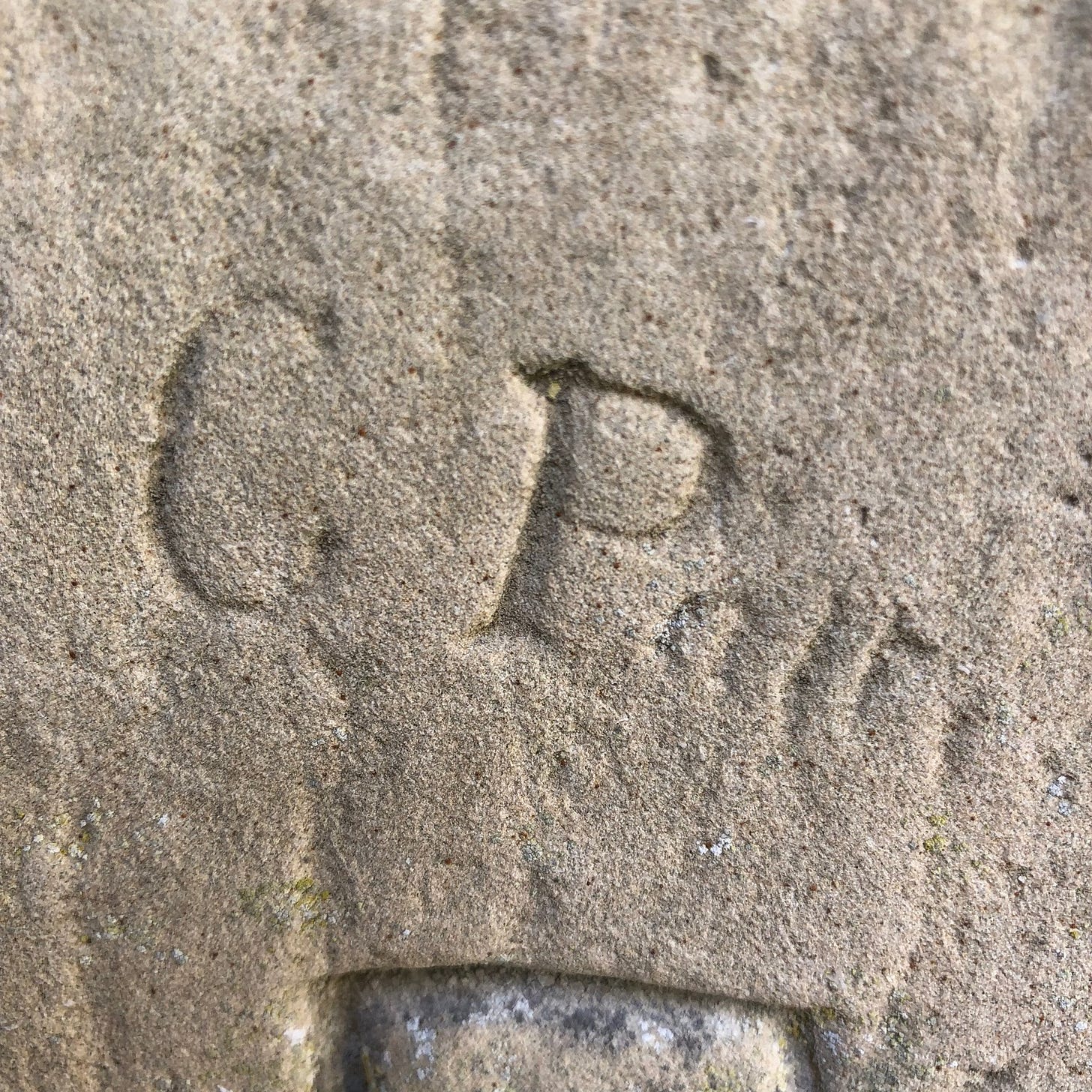

A declaration of love

AF and HM are together in the same heart. I’d love to think that these two are still happy together.

Hang on, though…

AF’s been BUSY! AF is now sharing rock space – and a heart – with KP, and is even keeping some options open beneath that inscription, scratching AF once more and leaving a blank space to, what, fill in later?

AF, you should be ashamed of yourself.

Self-expression in different languages and scripts

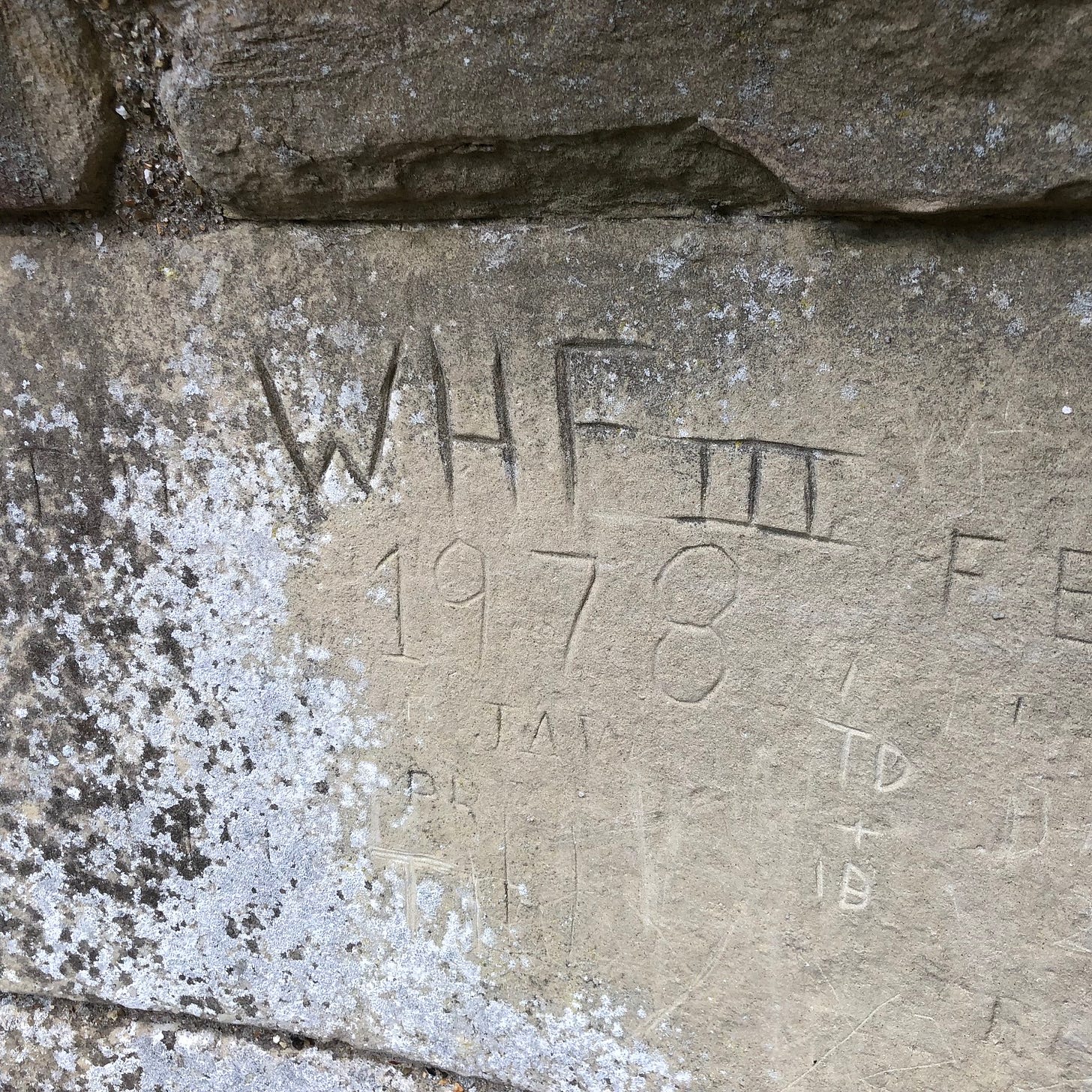

I loved this use of Roman numerals. Hello, 1979!

I wondered whether these might be symbols from the runic alphabet?

And these characters are beautiful:

Names and dates

I found examples of these – the ‘I woz ‘eres’ – everywhere I turned.

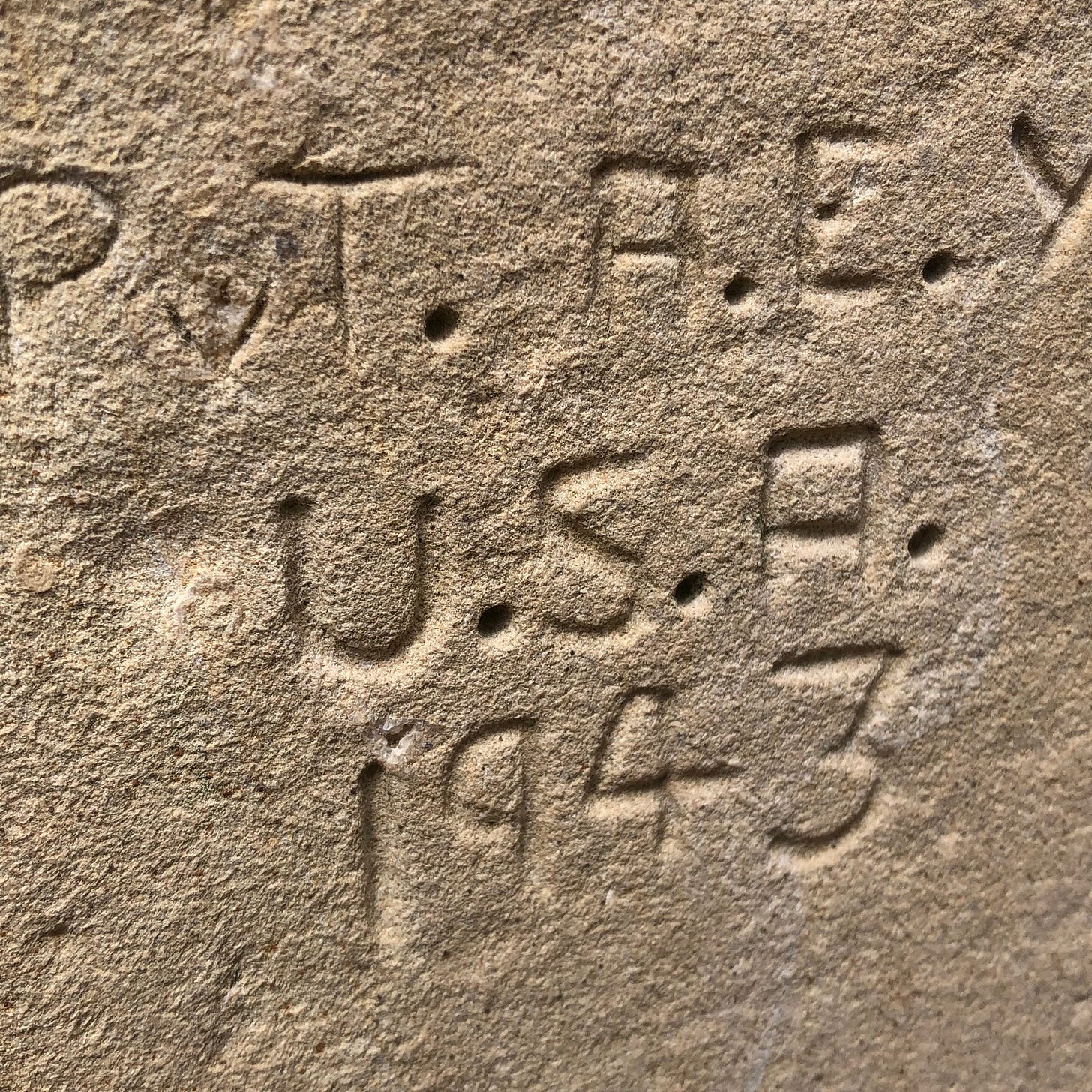

E. Burgess had made his or her mark on this impressive arch well over a hundred years ago, and – landing himself firmly in the category ‘I woz ‘ere’ in war year 1943 – so had PvT A.E.Y. from the USA. He – and I’m assuming this soldier had been a he – took trouble to add the dots between his initials. I wondered whether he’d used an awl, a screw, or even a drill. Whatever the tool, he scores points for consistency in both size and depth.

Graffiti made in memoriam

We are used to seeing names and dates inscribed on gravestones to memorialise those who have been lost. But this place – not a cemetery, but an ancient castle open to the public – had perhaps been special to Nicola, or those friends and family who had carved her name into this column to mark her passing eleven years ago:

Early in my visit I had heard a distant voice coming from the top of a spiral staircase high above me. ‘R J Buckland obviously ran out of time!’ was immediately followed by laughter. I’d looked up to see a man leaning over a steel barrier. ‘Look!’ he was telling his companions.

A little later, just after passing Nicola’s memorial column, I found myself where the chap had been leaning over the barrier. I think he’d been right. The second half of the name ‘Buckland’ had become so progressively shallow that the D was almost illegible – so perhaps Buckland had been tired.

What was more interesting to me, though, was that the name had later been bisected by the safety barrier which was clearly very much younger than the graffito.

I had no idea where R J Buckland was now, but I could sense his indignation. The presence of the name he’d left for us to discover had not swayed the installation of modern infrastructure; in fact, all over the castle, additions in the name of health and safety could be seen bisecting even decades-old specimens of graffiti.

And in other places, too, repairs to the castle’s ancient stonework had split, concealed or even removed parts of some marks that had been left for posterity.

Even more obvious repairs had been made to the castle over the years, with some stonework even plastered and painted.

On this patch here are these signatures in pencil:

S. Mitchell, Durham, 1950

HW to J, Aug 25, 1871. Or is it 1891? (Congratulations, you two, on your marriage!)

And a more modern scrawl: AK team 2014

In direct contrast to the inconsistent texture of the stone, this rendered surface was smooth. No wonder it had appealed to people to write on.

Yet on the stonework itself, the vast majority of graffiti had been incised, not drawn; even on this extraordinarily-textured chunk of rock: the victim, I think, of prolonged water erosion:

There was huge diversity of depth in the examples of graffiti I looked at – physical depth, I mean, not necessarily the profundity of their subject matter.

Some were remarkably deep, but some just mere scratches, where whatever tool that had been used had only just engaged with the stone surface.

In contrast, others were painstakingly complex, with curved letters wonderfully rounded, serifs1 as beautifully finished as Times New Roman’s.

I found an example of graffiti that was out of my reach. The castle had plenty of steps – I’d soon lost count of those spirals – but this example nowhere near a staircase must surely have been carved by someone standing on something:

Back downstairs, two RWs in the same area made me wonder whether they had been carved by the same individual perhaps years apart; as a child (lower left), then as an adult (upper right).

I wondered about RW. You see, until I married, I had always been RW.

And as RW I had been immortalised on a wall, in fact on an annual basis. Every summer, Grandpa would stand us against the painted render of his garage wall and carefully mark our heights with a pencil. On our visit the following year we’d be measured again, and by then those pencil marks of the preceding summer would have been painted to give them permanence, with the date alongside.

My brother and I had loved to compare our marks from one year to the next, impressing each other and ourselves by how much we had grown. Reader, I like to think that that record of our heights over so many years is still on the wall of that garage.

Across the board within the castle walls I found that the deeper, more complex examples of graffiti were located in the more out-of-the-way places. Of course, graffitists are less likely to be disturbed in hidden corners. 👀

And why might they not want to be disturbed? Well, leaving graffiti is a crime.

Graffiti is an offence of criminal damage and can be reported to your local police force. If prosecuted, the offender could face a fine or even imprisonment.

If you know someone who is causing graffiti call Crimestoppers on 0800 555 111

UK readers might be familiar with the term ‘ASBO’, or ‘Antisocial Behaviour Order’, and graffiti makes it onto the surprisingly limited list of what gov.uk considers to be ‘antisocial behaviour’.

Antisocial behaviour2 includes:

· drunken or threatening behaviour

· vandalism and graffiti

· playing loud music at night

Notwithstanding the law, for some there will always be the compulsion to make their mark on ancient stones. Never mind what we think about graffiti, there are always going to be people with a predisposition to inscribe their name on something for posterity.

Later, walking around the castle exterior, I found more graffiti in this north-facing alcove:

What a difference environmental conditions had made to the appearance of these words against their background. In this cool corner away from the sun, damp had prevailed, and the resulting black algae had emphasised the incised markings. The actions of nature and time had rendered their standard type bold.

Just as cobwebs and dust can veil an old artwork, we might find the effects of time and erosion – and yes, the weather unlocking the door for algae to get in – lessening the impact of a new graffito. Yet time can add to it a new significance; coming across historic examples of graffiti affords us fascinating insight into social history.

In Chapter VI of my favourite book, ‘Three Men in a Boat’ by Jerome K. Jerome, narrator J introduces ‘Musings on antiquity’.

Why, all our art treasures of to-day are only the dug-up commonplaces of three or four hundred years ago. I wonder if there is real intrinsic beauty in the old soup-plates, beer-mugs, and candle-snuffers that we prize so now, or if it is only the halo of age glowing around them that gives them their charms in our eyes. The “old blue” that we hang about our walls as ornaments were the common every-day household utensils of a few centuries ago; and the pink shepherds and the yellow shepherdesses that we hand round now for all our friends to gush over, and pretend they understand, were the unvalued mantel-ornaments that the mother of the eighteenth century would have given the baby to suck when he cried.

Will it be the same in the future? Will the prized treasures of to-day always be the cheap trifles of the day before? Will rows of our willow-pattern dinner-plates be ranged above the chimneypieces of the great in the years 2000 and odd? Will the white cups with the gold rim and the beautiful gold flower inside (species unknown), that our Sarah Janes now break in sheer light-heartedness of spirit, be carefully mended, and stood upon a bracket, and dusted only by the lady of the house?

Taken from ‘Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog)’ by Jerome K. Jerome, 1889

To use Jerome’s term, today’s commonplaces – the cheap trifles – of twenty-first century graffiti scratched into the stone walls of an important historical site might just yet become tomorrow’s prized treasures of social history.

I don’t see the predisposition for people to make their mark ever waning: it seems that the need to scrawl ‘I woz ‘ere’ or its equivalents on an ancient monument still overwhelms some members of our society.

Although I am not condoning the act of making graffiti I nevertheless feel it earns its keep in its role illustrating social history. How things are viewed over time is subject to change, and perhaps the words that are scratched into walls today will themselves fascinate those who follow tomorrow.

Love,

Rebecca

If you’ve enjoyed this post, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

If you’ve been following my correspondence with my fellow Substacker Terry Freedman you’ll know that it’s my turn to reply to him on Wednesday! You can find his latest letter to me here, and links to our entire canon of letters here. Do have a read of our light-hearted exchanges about British life over our shoulders!

If you’ve been following the brief daily posts in my Jog log 🏃🏻 you’ll know that my slow-and-steady training for the local pub-to-pub 5k race in a few weeks is well and truly underway. You’ll find the Jog log 🏃🏻 in the navigation bar on the web version of my Substack homepage, or, if you’re on the app, click on post 86. Jog log 🏃🏻 to find links to all the entries. I’m really enjoying my journey back to fitness, and you’re very welcome to join me (or cheer me on!). 😊

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

The message you were asking about is in an ancient Mayan script and translates as "Beware of pickpockets"

This is fabulous Rebecca. I’m a sucker for detritus, of all kinds. It strikes me that graffiti is kind of like marginalia... but for buildings instead of manuscripts. Really enjoyed this ❤️