Dear Reader,

When I was little, shopping for wellington boots would always happen at Culverwells, the outdoor goods merchant in the nearest town. We’d go there pretty often for such things as compost, pea sticks, grass seed, lawnmower parts and hand tools, and my brother and I became firm friends with Mr Turner, the sales assistant in his brown utility jacket. On every visit he’d reach into a sack of bone-shaped dog biscuits and hand us one, which we’d guard carefully until we next saw Jessie, the Old English sheepdog belonging to our neighbours.

I forget which of us was responsible for one day telling him that we didn’t actually have a dog, but I certainly remember that our supply of free dog biscuits ended unexpectedly suddenly. 🤔

Twice a year or so, as our childfeet grew, we would head to Culverwells to replace our wellies.

Or, at least, one pair of wellies. As the smaller of my parents’ children, I qualified for second-hand ones. The boots with my name on would be the ones which no longer fit my brother’s feet. His new boots were from the display of green Dunlops on the racks at the shop.

It didn’t occur to me to mind – and why would it? As my feet grew out of my wellies, there was a pair in waiting. I wasn’t the one who’d have to stomp up and down the aisles of Culverwells to try out my next pair: the decision about mine had been made.

Sorted.

One day I ended up with my own pair of brand-new wellies – and not the standard green Dunlops I’d always been used to. These were special – not only different to any I’d ever had before, but more importantly, different to everyone else’s in the family.

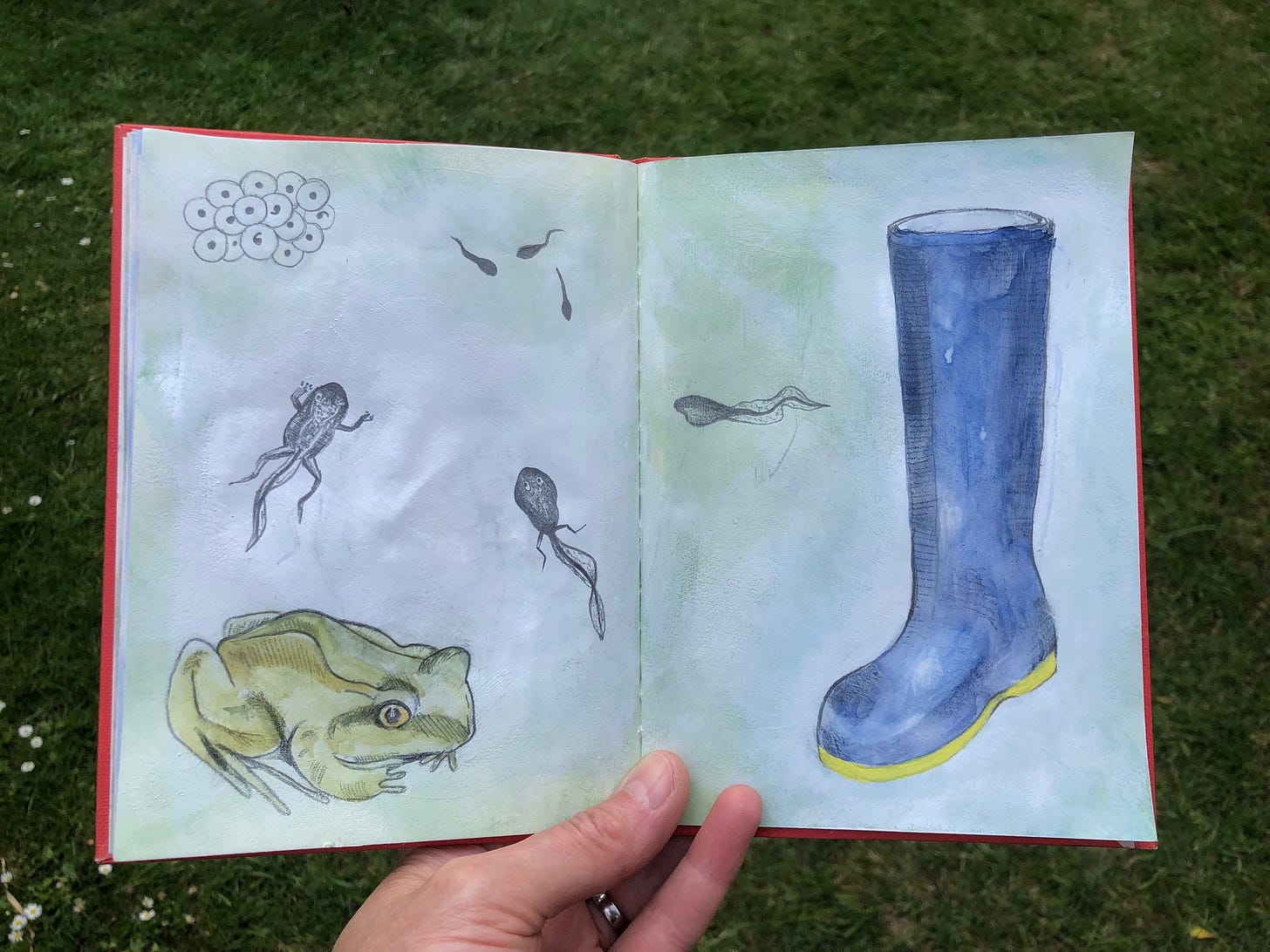

They were blue with bright yellow soles, and an area of ridge detail on their outside edge as a sort of ankle protector. Reader, I loved those wellies. They were so precious that for a while I would even walk around puddles rather than through them.

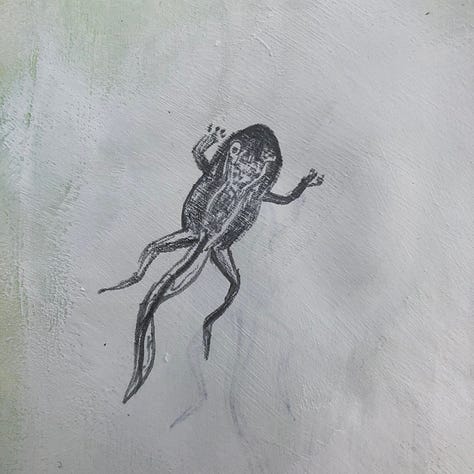

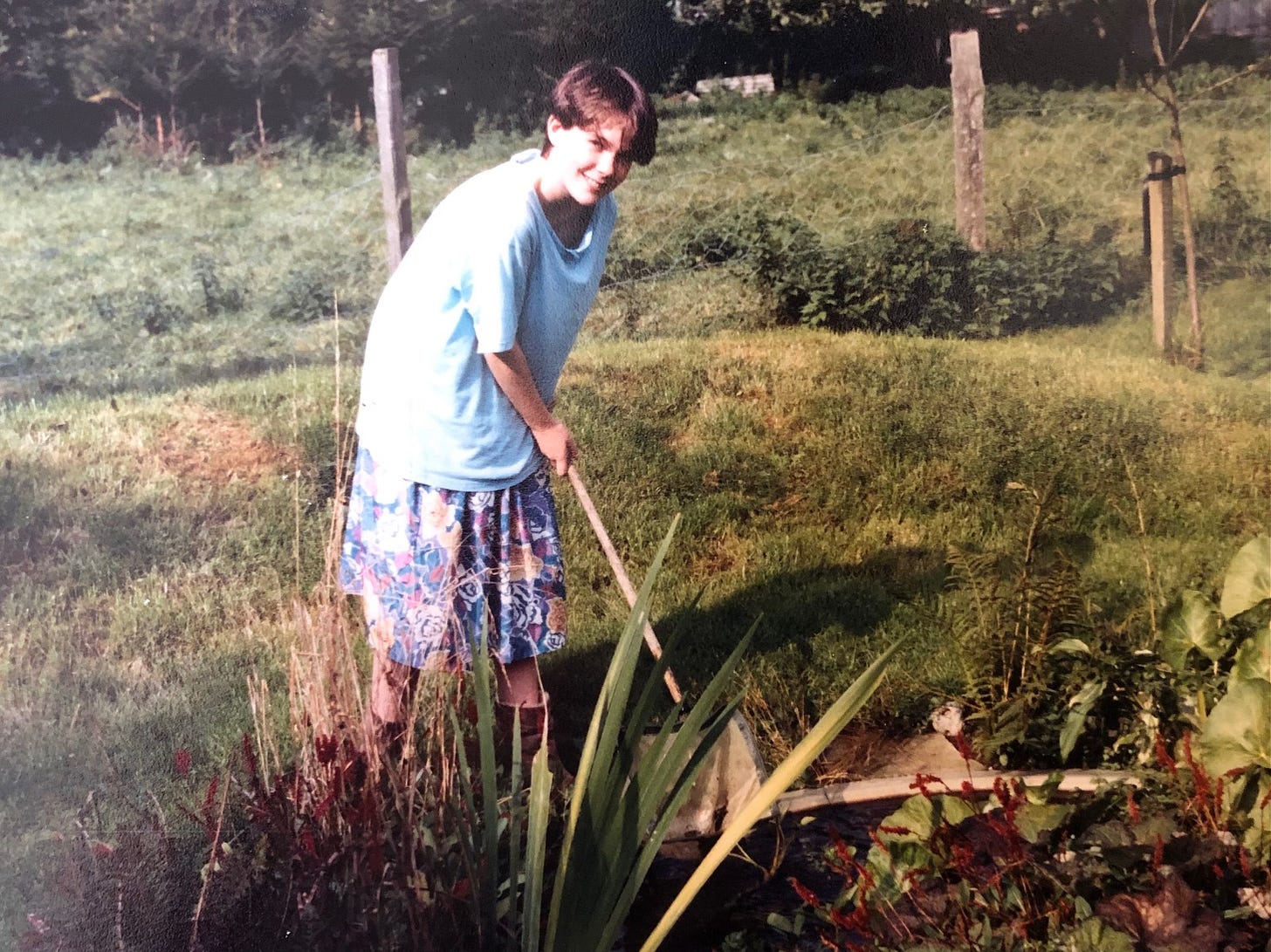

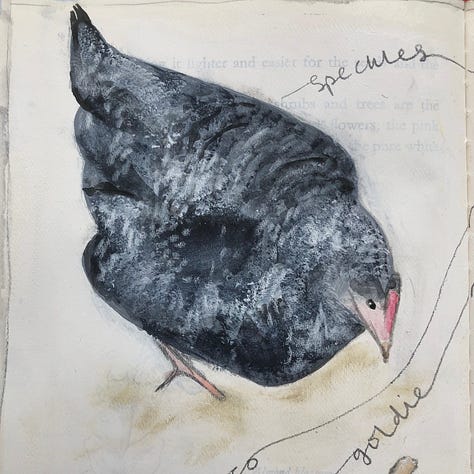

As a child I spent a great deal of time outside, not just helping – and playing – with my friends the sheep, the hens and the goats, but also enjoying getting to know the smaller creatures that frequented our garden. I had a particular fondness for frogs.

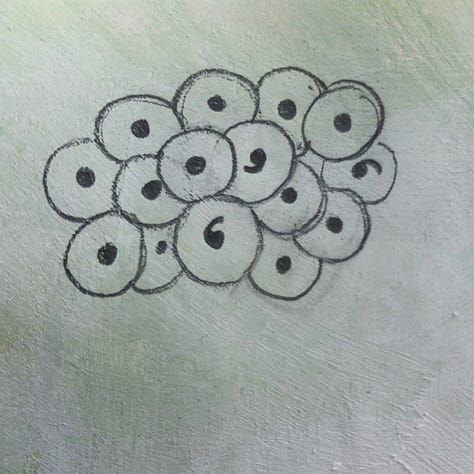

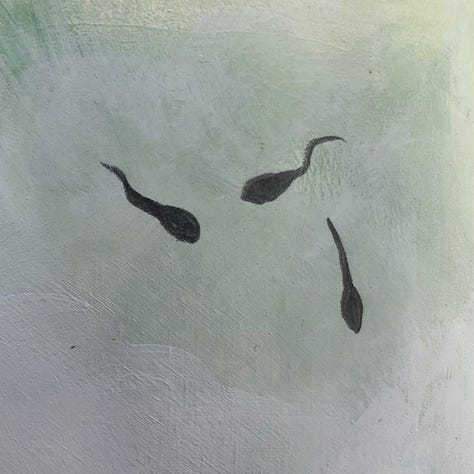

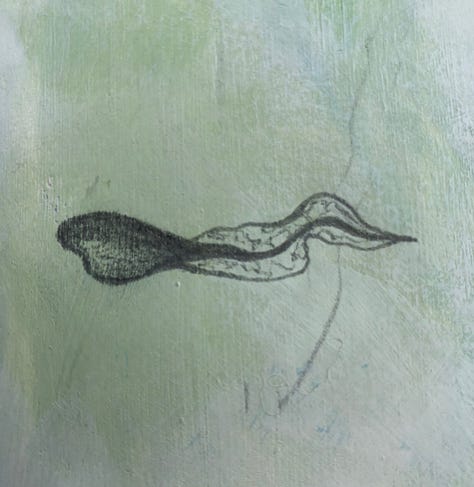

Before we had a garden pond, every spring we would collect – with permission – a small mass of frogspawn from someone who did have a pond to pop into a little aquarium in the kitchen. Brand-new frogspawn is extraordinarily dense and compact: the eggs are tiny. It is only when the spawn has spent some time in water that it hydrates, swells and grows into that familiar bulging mass, those little black dots so beautifully centred in their jelly globes. From that point on, we’d watch as the tiny full stops punctuating the spawn in our aquarium would elongate into little commas, and I’d be fascinated once the black lines of embryonic tadpoles would start to move, snapping themselves back and forth from what I imagined to be a central hinge as they limbered up for life in the water.

As the tiny tadpoles hatched they would stick together in a writhing black inky mass on top of the floating pile of disintegrating jelly.

We didn’t have a pond in the garden until I was eight or so, and the rule was that as soon as our kitchen tadpoles had begun to grow their tiny back legs they would be taken back to the pond the spawn had come from.

When my parents decided that we would dig a pond of our own, my brother and I literally dived in to help in the process, christening the newly-filled butyl-lined crater by jumping straight into it.

As the water got murkier and nature began to do her thing with this brand-new aquatic ecosystem, I became obsessed with the little creatures I would find wriggling and squiggling their way through the water. And every spring I’d keep a keen eye out for the appearance of frogspawn.

There hadn’t been very many frogs in the pond to start with, but that didn’t stop me looking.

In time, as the growing kingcups and bogbean softened the margins, the water lilies launched their amazing blooms like exotic lotus, and once I knew where to look for it, animal life in the pond became more obvious.

There was a little rock half-in, half-out of the water, and I would often find a big frog lurking between it and the edge of the pond. He didn’t seem to mind my disturbing him every day after school: after untangling his soft limbs from one another he would give a huge kick from his back legs to dive deep, deep, deep down to the bottom. Back he’d be in his favourite spot in time for the next day’s interruption to his afternoon snooze, regular as clockwork.

Our pond had a liner of heavy-duty, waterproof fabric that didn’t tear easily, but which might get a tear if something sharp were to meet it. It was for this reason that this little wannabe pond-dipper was not allowed to dip – well, not with a net, anyway.

But the liner held secrets that I could still access. With all the time I was spending beside the pond I had got to know its layout pretty well, and had noticed some deep, vertical folds within the arc of one of the curves outlining the pond. I could reach one of them with my right hand, dipping my arm elbow-deep into the water and feeling for where the fold began to rise from the base of the pond. If I was careful, I could very gently squeeze my hand into the narrow pocket of the liner and see what – or who – I could find.

My prize one day was a frog. Two. No, three! How many froggy friends might be squeezed into all of the pockets in the liner added together? Could be hundreds, I thought with excitement.

Looking back now at my pond exploits as a child, as I write this I am absolutely not surprised that for the first couple of years no frogs ever saw fit to reproduce there. If we wanted tadpoles, we would still have to import spawn from outside.

One summer, friends of our family had dug their own pond and were also seeking to stock it with the little creatures of which I was so fond.

‘Can we have some of your frogspawn?’ asked P on the phone the next spring.

We had to disappoint him. ‘Sorry, there isn’t any.’ After all, our own frogs were far too busy being stirred up by the likes of me after school on a daily basis to be able to concentrate on their seasonal priorities.

On a very puddly walk on Ashdown Forest with P and his wife J not long after his phone call, we came across a patch of water with an unexpected surprise: a clump of frogspawn. This wasn’t a pond, or even a slow-moving stream, but simply a soggier-than-usual area of wet heathland1.

‘Just what I’m after!’ called P in triumph.

He cast about for something to fish the frogspawn out of what was little more than a shallow puddle. But we were out on a walk – and there’s not much call for a bucket or a repurposed ice-cream tub on one of those just on the off-chance of needing to cart a handful of wet jelly home.

What followed was what I felt to be – both at the time and still now, forty years on – a very silly suggestion.

‘How about Rebecca’s welly?’

That’s right. One of my gorgeous blue wellies with yellow soles.

With no awareness of my consent having been granted for what was about to happen, I found myself suddenly a boot down, and to my horror it was being used to scoop up a jellied mass of quivering cargo. Despite being very fond of P, the hijacking of my welly was too much to bear, and – grumpy by small-child nature – I didn’t speak to him for the rest of the day.

Mum laughed like a drain last week when she and I were comparing recollections of this story.

‘How did I get back to the car park with just one boot on? Did you carry me? And who carried the welly?’

‘I didn’t carry either you or the welly. I expect Daddy gave you a piggyback, and of course P had to carry the welly. You know the rule: you want it, you carry it. Nothing to do with me!’

‘Good!’ I told Mum, with feeling. Because, Reader, this stuff matters.

‘You want it, you carry it’ was always the rule on family outings, and on that day I learned that it applied to adults equally, including P and his frogspawn.

P tipped the spoils of the welly trip into his pond, where the spawn eventually hatched into his first generation of tadpoles. I had my welly returned, clean and dry, and it was reunited with its dark blue, yellow-soled twin. My grumpiness was forgotten.

On my next birthday I was taken outside to unwrap my present.

‘Cor, it must be HUGE!’ I told my brother in excitement.

Dad opened the garage door to reveal the solid shape of something extraordinary hidden under several overlapping dust sheets.

I pulled off the sheets. It looked like a giant, kidney-shaped bathtub, with two shallow ends and a deeper bit in the middle.

‘What on earth is it?’ I asked, just as my brother handed me his present. It was a fishing net.

‘It’s a pond of your own!’ Dad asked. ‘It’s fibreglass, so you can fish around for your frogs in this one!’

‘Or even wade in it!’ said Mum. ‘Just remember to wear your wellies!’

Love,

Rebecca

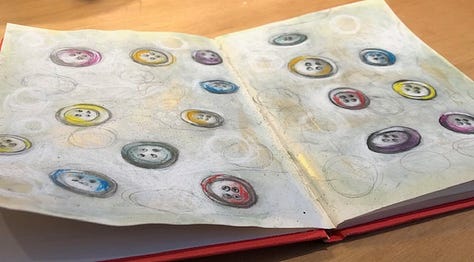

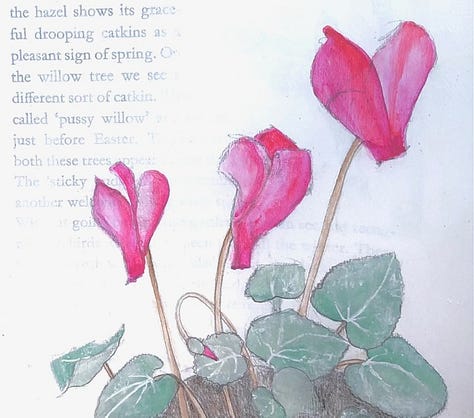

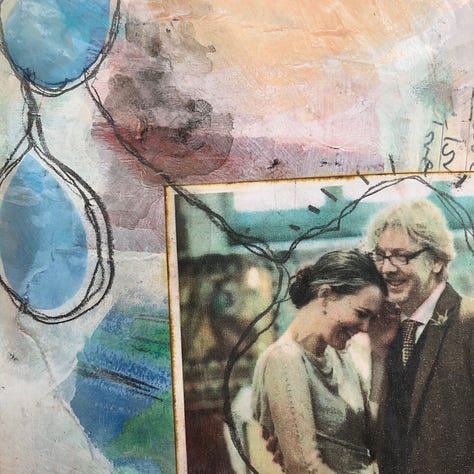

Here’s the story so far of my ‘altered book’ art journal featured in my monthly ‘Art & Treasures’ series of posts:

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, the sixth in a regular series exploring some of my memories in words and pictures, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you! You’ll find all the posts in this ‘Art & Treasures’ series here.

If you’ve been following my correspondence with my fellow Substacker Terry Freedman you’ll know that it’s my turn to reply to him on Wednesday! You can find his latest letter to me here, and links to our entire canon of letters here. Do have a read of our light-hearted exchanges about British life over our shoulders!

My next ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’ post will of course be published next Saturday.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

Heathlands are intrinsically dry landscapes, based on sandy and acid soils.

Because sand is so permeable, it also means that the small amount of wetland which does occur on heathlands, is rarer, and has proportionately even more value than it would have in an otherwise ‘wet’ landscape.

Much of our heathland has been placed under forestry management and has been grip drained, which means that we have lost important areas of wetted heath across Sussex.

Wet heaths are important habitats for a number of nationally and locally rare species.

Small areas of wet heath are known to occur in Sussex heathlands including… larger areas in Ashdown Forest.

Taken from the Sussex Wildlife Trust website.

After I finished reading this beaut I was searching for the “love” button. Wait, that sounds dirty. But you know what I mean. You’ve sent me hurtling back in time, and taught me a word (frogspawn) that eclipses the poor tools we were using to describe same, in southern Connecticut (frogs eggs--how pedestrian). (Not sure I prefer the German, actually, which--as usual--sounds like a curse.) But oh those childhood rambles, the mystery of a life outside, the dizzying life cycles, the dear parents who offer it up, saying “look how amazing all this is!” And “we’ll put the frogspawn in your welly!” A parent can’t do better for a child than that.

Love this post as it had me back in the land of childhood memories, too, of growing up with a giant maple tree woods with pond right behind my home, the very best place to explore. Your childhood sounds so lovely and idyllic. Where can I buy your book? "You want it, you carry it" is perfect: for the library, the grocery, the thrift store, walks! Read this one while drinking my morning coffee. Your art is beautiful.