67. When bluebells seemed like fairy gifts

A (quiet) fanfare for the silent eloquence of a springtime treasure.

The lines ‘When bluebells seemed like fairy gifts’ and ‘silent eloquence’ in the title of this post are taken from ‘The Bluebell’ by Anne Brontë.

Dear Reader,

Spring provides us with plenty of goodies to fuel the language of poetry. There is birdsong and sunshine, and the new season’s sights, sounds and scents abound: spring is a delight.

Early last month I spotted the first shy wood anemone on a woodland walk. I’m always keen to observe the annual variation in the fickle timetable of the flowering of anemones and bluebells: in the early warmth of last year’s spring they were out together in a burst of white and blue in one glorious eyeful, but this year, when spring has been taking its sweet time to get started, the anemones enjoyed an almost independent season. For a few weeks they had owned the woods and verges.

Wood anemones are unassuming flowers with – like me – a strict bedtime. They don’t open their petals until the light of day is enough to wake them, and as the evening light fades, so does their energy. At night they close their flowers: each multi-petalled bloom folding into a circle like the moon above them.

Bluebell foliage was already in evidence of sorts in February: the glossy fresh green spears pushing their way up through a rustling brown carpet of beech leaves, but I didn’t see my first bluebell in flower until mid-April. By then the anemones were already carpeting the woodland floor with their stars, the bluebells playing catch-up to their head start.

In my south-east corner of England, it is in April and May that we welcome a glorious showcase of British native bluebells, Hyacinthoides non-scripta. Blue is often considered to be a cold colour, but bluebells are a warm blue, almost violet, and the vast swathes of this beautiful flower carpeting forest floors at this time of year are absolutely breathtaking.

Our native bluebell, Hyacinthoides non-scripta, otherwise named common bluebells, English bluebells, British bluebells, wood bells, fairy flowers and wild hyacinth, is an early flowering plant that naturally occurs in the UK. It appears in ancient woodlands and along woodland edges in April and May. Millions of bulbs can exist in just one wood, giving rise to the violet-blue ‘carpets' that are such a springtime joy to walk through. This early flowering allows them to make the most of the sunlight that is still able to make it to the forest floor habitat, before the canopy becomes too thick. Native bluebells are protected in the UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981.

The scent of a bluebell is not unlike that of its close and larger relation, the hyacinth. Yet the all-consuming scent around me as I walk through a softly sunlit bluebell wood on a warm day is almost overwhelming: thousands of flowers share their scent with passers-by in a profusion of perfume.

Ah, that perfume: if only it could be gathered up and bottled. Well, London perfumier and Royal Warrant holder Penhaligon’s, established in 1870, has been making its fragrance ‘Bluebell’ since 1978. It describes the scent as: “A pure and unadulterated distillation of the scent of bluebell woods”, and tells prospective purchasers that “If you go down to the woods today... a fragrant carpet of bluebells awaits. Breathe deep. Citrus, hyacinth, clove. An eau de toilette reminiscent of childhood escapades in the fresh, dewy spring.”

For me there’s something rather more special – not to mention much less expensive – in seeking out the scent of real bluebells in season in April and May. Just like I don’t enjoy eating asparagus as much outside its season of St George’s Day to Midsummer’s Day, I’m not sure I need to drink in the scent of bluebells when the flowers themselves are not in evidence.

There’s another kid on the block of blue spring flowers at this time of year, though, and the Spanish bluebell, Hyacinthoides hispanica, is a pretty flower in its own right, with its unscented flowers arranged all around its erect stem.

Yet despite the springtime British splendour of a carpet of bluebells, the posture of a single native bluebell is lowly and unassuming. Its head is bowed, and the bells hang down from its arched stem.

This unexpectedly humble aspect of a bloom which in its Maytime multitude is easy to miss endears it to me as much as it did to writers of the past.

Anne Brontë included these words in her poem ‘The Bluebell’:

…

There is a silent eloquence

In every wild bluebell

That fills my softened heart with bliss

That words could never tell.

…

But when I looked upon the bank

My wandering glances fell

Upon a little trembling flower,

A single sweet bluebell.

…

O, that lone flower recalled to me

My happy childhood's hours

When bluebells seemed like fairy gifts

A prize among the flowers

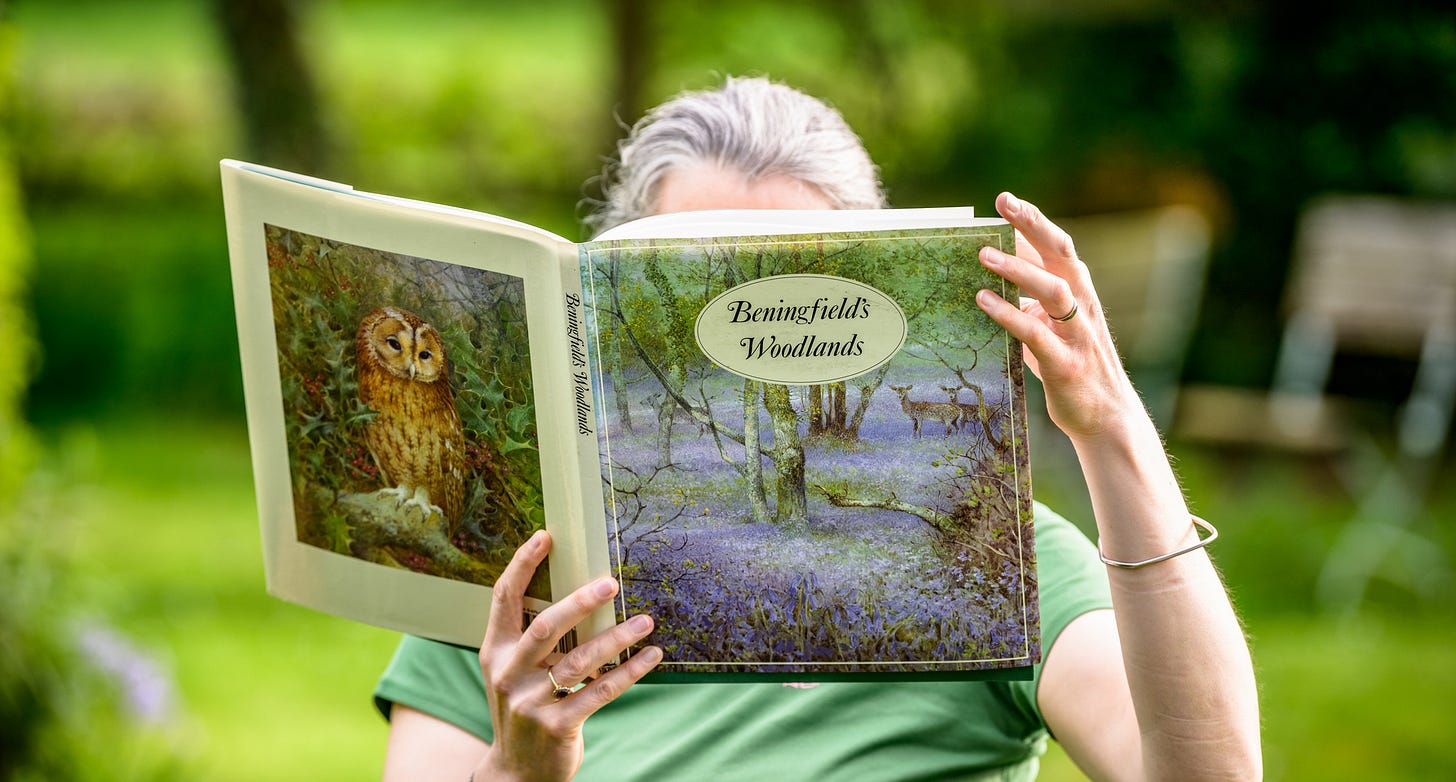

In his stunning book ‘Beningfield’s Woodlands’ nature artist and writer Gordon Beningfield explains why bluebells are so special:

Bluebell woods are one of the wonders of the world, and nowhere are they more spectacular than in Britain. The carpets of violet-blue flowers shimmering under the dappled spring sunlight in a hazel coppice of oak wood are an unforgettable sight.

The damp climate of Britain clearly suits bluebells… Over most of southern England, however, they seem to need the moist atmosphere of woodlands, though they will survive in hedges and under bracken where the trees that have sheltered them from time immemorial have been destroyed.

Bluebells spread very slowly – the heavy black seeds that drop out of their seedcases are unlikely to travel very far – and bluebell woods are mostly ancient in origin. This means that even if modern tree plantations were suitable for bluebells (which they are not), it would take a very long time – centuries perhaps – for new woodland to develop the swathes of flowers that are a springtime national treasure. Our ancient bluebell woods are irreplaceable, and, like woods in general, have fallen victim to the government-encouraged greed of farmer and foresters.

Taken from ‘Beningfield’s Woodlands’ by Gordon Beningfield, published by Viking, 1993

According to the Wildlife Trusts, the UK’s woodlands are home to almost half of the world’s population of Hyacinthoides non-scripta, but it seems that these bluebells – the ones which in their glorious violet-blue carpets bring such gorgeous delight to my walks at the moment – are under threat from their more robust and upright continental cousins.

In the case of Hyacinthoides hispanica – rather like the grey squirrels threatening our native species of reds: a topic that I enjoyed exploring in my post ‘Going nuts: a nature story’ – the Victorians seem to have a lot to answer for:

The Spanish bluebell was introduced into the UK by the Victorians as a garden plant, but escaped into the wild – it was first noted as growing ‘over the garden wall’ in 1909. It is likely that this escape occurred from both the carefree disposal of bulbs and pollination. Today, the Spanish bluebell can be found alongside our native bluebell in woodlands and along woodland edges, as well as on roadsides and in gardens.

This member of the bluebell family is not quite so blue: it is paler perhaps, with its violet tones not as saturated as those of its native cousin. Standing tall in spring flowerbeds and borders Spanish bluebells make a confident impression: their bell-shaped flowers opening wider than those of their native cousins, petals outstretched. In a woodland setting these blooms would be obvious strangers to their bowed-headed cousins which have naturalised in English woodlands over generations, but as flowers to enjoy in the garden they are beautiful, and I’m pleased to have them in my own back yard.

It’s not as simple as that, though. It seems that our native variety is under threat not only from the relative dominance of the more robust hispanica variety in competing for light, space and nutrients, but in the ability of the two forms to readily hybridise. The result is – yes – another beautiful flower, a further string to springtime’s bow; a new painting in the gallery of seasonal wonder, but this hybridisation – and subsequent colonisation by those hybrids – presents great risk to our native community of bluebells.

Reader, there is surely room for flowers in all their variations, and I love that the annual competition between the wood anenomes and bluebells to flower at the same time changes its favour almost every spring. Yet I am sad at the dominance of a bluebell variety so closely related to the one which has naturalised in British woodlands over generations putting at risk our opportunity to enjoy Beningfield’s and Brontë’s favourites in the years to come.

Love,

Rebecca

ADDENDUM

In her comment on this post, which I published on coronation day,

of was kind enough to let me know about this very fitting poem by Cicely Mary Barker, author of the 'Flower Fairies' books.Thank you, Julie: I can’t imagine a more perfect conclusion for this post on such a special day.

Here is the first verse of ‘The Bluebell Fairy’:

My hundred thousand bells of blue,

The splendour of the Spring,

They carpet all the woods anew

With royalty of sapphire hue;

The Primrose is the Queen, ’tis true.

But surely I am King!

Ah yes,

The peerless Woodland King!

If you’ve enjoyed this post, do please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

Thanks to Julie Hester letting me know about a very coronation day specific bluebell reference I have updated my post to include the first verse of 'The Bluebell Fairy' by Cicely Mary Barker. Thanks, Julie!

Gorgeous photos. I'm recalling my (American) daughter's early obsession with the Flower Fairies books, and just looked up the Bluebell Fairy. Here on coronation day it's perhaps appropriate:

My hundred thousand bells of blue,

The splendour of the Spring,

They carpet all the woods anew

With royalty of sapphire hue;

The Primrose is the Queen, ’tis true.

But surely I am King!

Ah yes,

The peerless Woodland King!