Dear Reader,

Where I live in south-east UK the only squirrels we see are grey. Our native species, the red squirrel, is limited to tiny populations in a very few tucked-away locations in the north of England, Scotland and a couple of small islands off the coast.

Like so many things with which we are now very familiar in contemporary life, grey squirrels first came our way from across the pond. Native to North America, they landed on British soil in the 1800s, and they were first recorded escaping from captivity and establishing a wild population in 18761.

Victorian Britons loved to travel and bring back souvenirs, and in the case of living flora (such as Japanese knotweed and Himalayan balsam) and fauna like the grey squirrel, these introductions have in some cases proved to be invasive.

I suppose we rub along okay with the grey squirrels in our garden, but they’re a cheeky and determined bunch, and it’s a pain trying to keep them off the bird feeders. One has recently discovered the storage bin in which we keep our bird seed, and I’m sure it’s plotting a break-in.

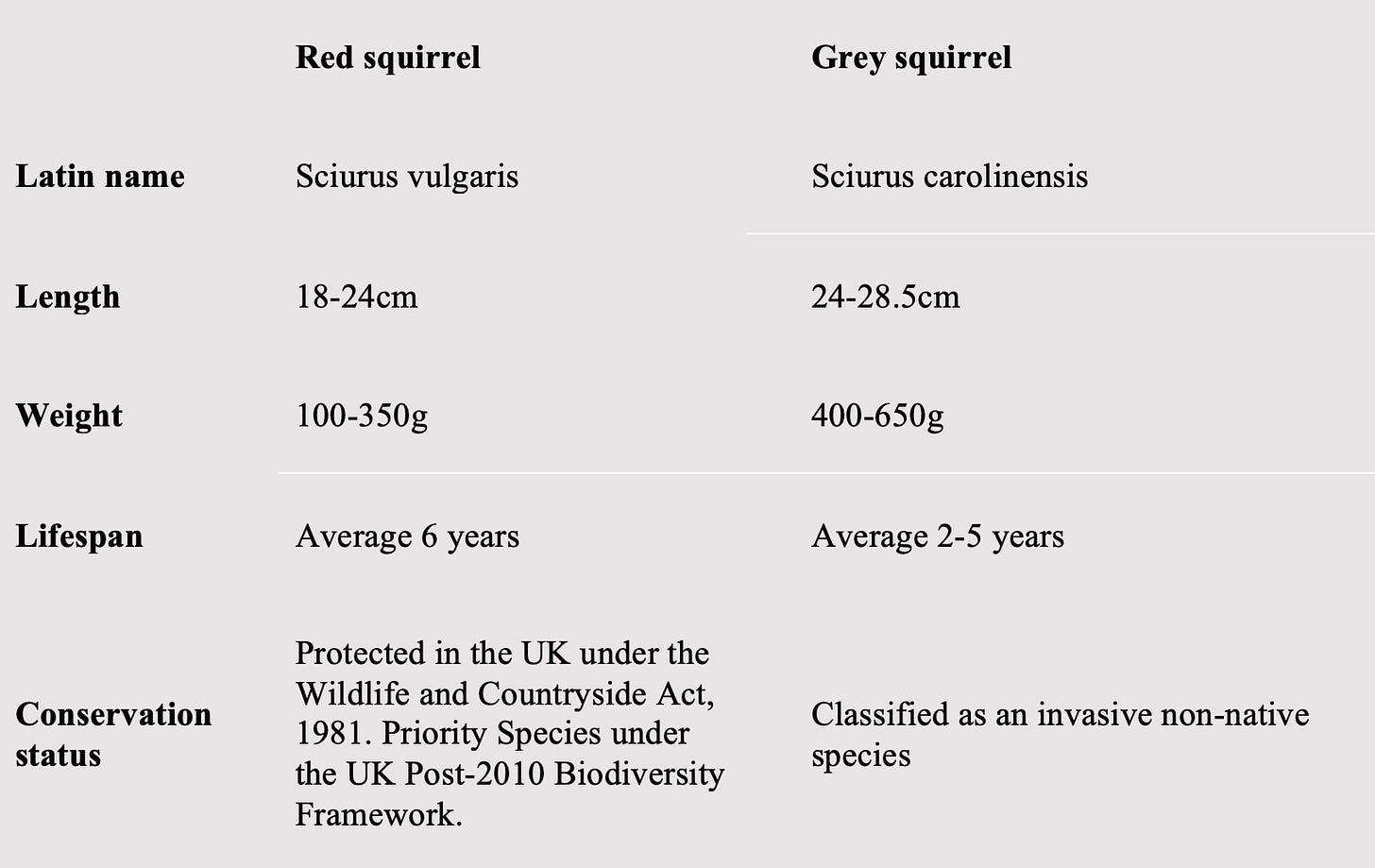

They’re both squirrels, but the two species are very different. The Wildlife Trusts2 website explains how:

Red squirrels are threatened, and according to The Wildlife Trusts, this is why:

Grey squirrels compete more successfully than red squirrels for food and habitat. They are larger and more robust, and can digest seeds with high tannin content, such as acorns, more efficiently. This forces red squirrels into other areas where they can find it more difficult to survive.

Grey squirrels also transmit a squirrelpox virus which can normally kill red squirrels. Once infected, red squirrels often die of starvation or dehydration.

The grey squirrel is the main reason for the decline of the red squirrel. Habitat loss has also contributed to the red squirrel’s decline. This occurs when areas of woodland are destroyed or become separated by development and changing land-use. This leads to isolated areas which cannot sustain viable populations of wildlife, including red squirrels in some places. Squirrelpox virus is fatal to red squirrels but is carried by grey squirrels without causing them any harm.

I’m often aware of grey squirrels on my walks: I see them either sitting on branches posing picturesquely, or bounding across my path and scooting up the nearest tree. The sound they make is like nothing else – a sort of textured, not-quite guttural chattering – and I swear they openly laugh at any dogs that might be in pursuit of them.

We were on the Isle of Wight – one of the very few enclaves for our native species – for work last weekend. There are no greys on the island, but I’d never yet spotted a red squirrel on our regular visits. On our way to the ferry port for our boat home, though, we decided to check out a nature reserve with an active population of these rare creatures.

This was an impromptu recce for Jim’s latest book project: the subject matter is woodlands, and a diverse range of trees, plants and forest fauna will be making an appearance.

But today, would the squirrels?

On what had been a disappointingly grey day so far, we arrived at the reserve in glorious sunshine.

‘Well, we’re never going to see one’, said Jim, ‘but keep your eyes peeled.’

Mere moments later I watched as a fine-featured gingery orange animal made its way down from an ivy-wrapped trunk and bounded towards the hide. Not having expected to see a squirrel at all, this member of what I had thought to be a shy, retiring species leapt onto the handrail of the walkway to the hide and careered along it until it almost collided with Jim’s camera lens.

‘WOW!’ he said. Then, to the squirrel: ‘Back off a bit, would you? I didn’t bring my macro!’

In the two hours we’d had to spare before needing to check in for our ferry crossing we watched four red squirrels: two bright orange ones – one with a parting of hair at the end of its tail – and two more which were a much darker reddish-brown.

Two were shy and careful, the others bold as brass.

We weren’t the only people around. This was Sunday lunchtime, after all, and in dry and unexpectedly sunny weather there were couples and families out and about.

Walking away from the hide and towards the centre of the reserve we came across two small children holding their hands high and out, palms horizontal, as great tits3 and robins took it in turns to help themselves to seeds from their open hands.

The seeds were for the birds, but the children’s mother was holding a handful of shiny hazelnuts. She told us where she’d been putting them down. ‘For the squirrels!’ she said. ‘Help yourself to some – you never know who’s around!’

I thanked her, and we each pocketed a couple.

Jim suddenly asked: ‘Shall I ring Wightlink? See if we can postpone our crossing to tomorrow?’ I wondered if he was teasing. Then: ‘There’s a campsite just at the bottom of the hill there – there’ll be a spot for us, I’m sure!’

‘Great idea!’

Ferry rebooked, and with the hazelnuts rattling in our pockets, we walked back to the van and headed for the campsite, where thanks to another quick phone call a pitch was being held for us.

By the time we’d nipped to the farm shop to stock up on evening provisions we hadn’t anticipated needing, it was already 3pm, and the sky had turned grey when we got back to the reserve.

‘Is this a mistake?’ Should we have quit while we were ahead?’ Jim was downhearted. At lunchtime we’d seen so many squirrels, and now there were none.

We laughed about the one that had tried to take on Jim’s camera earlier. ‘Yeah, where’s he now?’

While we lay in wait for whoever might come to snaffle the hazelnuts we’d put ready, I thought about the first red squirrel I’d ever seen: it had been helping itself from the hinge-lidded box on the side of Grandma and Grandpa’s window frame.

My grandparents’ bungalow had a glorious view over Lake Ullswater in the Lake District National Park in the north-west of England. Halfway up Knotts Fell and surrounded by trees, their garden was a natural playground for red squirrels.

Grandpa had made two wooden boxes with Perspex front panels, screwing one to each side of the recess of their large picture window overlooking the lake.

Long before ordering groceries online had become commonplace – in fact before the internet had even been invented – the ‘shop on wheels’ would drive up the fellside lane and throw open its doors to residents, one household at a time.

The business owner knew that a net bag of hazelnuts in their shells was an essential part of Grandma and Grandpa’s regular grocery shop, and those two boxes would be kept topped up with the tasty treats.

And the squirrels knew exactly where to go – they’d check out the first box, then scamper along the windowsill to the other. We’d spend hours watching them.

When Grandpa had gone the squirrels remained, until new neighbours moved in next door and almost immediately set about cutting down the big hedge between their plot and Grandma’s. Reader, that hedge had been the squirrels’ highway.

So, not long before Grandma left us, her squirrels left the garden. I like to think that they didn’t move too far, and that some of their progeny might still be around.

Now that it was so much cooler, we were the only people left in the reserve. There was still plenty of wingborne activity, though: lots of little birds were flitting between the trees, and a single female mallard flapped her feet on the path as three drakes chased her in springtime excitement. The fellers were wary of us and kept their distance, but Mrs Mallard was quite happy to walk beside us for a bit. The drakes eventually gave up and flew back down the slope towards the reedbeds. Fine by all three of us.

Mrs M went on her way, and we sat on a log to watch the smaller birds dipping in and out of the trees. The dunnocks were shy with us but flirty with each other, and the robins knew they were beautiful and were taking any opportunity they could to pose for Jim’s camera. The blue tits and great tits were on a neverending loop: the same few birds circling in just one orbit.

And there it was: one of the shyer, darker red squirrels we’d spotted earlier was busying itself with the dead leaves a little way down the slope. It didn’t get nearly as close to us as its brighter buddies had earlier in the day, but this was arguably more authentic wild squirrel behaviour. We were thrilled to watch it in action, but photo opportunities were limited now that it was nearly dark.

‘We should’ve got that ferry!’ Jim said, looping his camera strap back over his shoulder.

‘Well, we haven’t got to check in until ten tomorrow.’ I was trying to encourage him. ‘Early start?’

We set off on foot next morning at seven. Jim was weighed down with his cameras and lens pouches, and I was guarding four precious hazelnuts.

(Reader, they were important.)

The birdsong was magical – it was a bright morning with pale sunshine, and although it was cold the birds certainly didn’t seem to mind.

It wasn’t just the tiny birds we heard, though: ‘our’ mallards were around, and there were crows, jackdaws and jays making a racket. In the distance we even heard a woodpecker drumming.

We drank in the sounds for half an hour before the star of the show arrived. It was the smaller of the two bright orange squirrels we’d seen the day before, the one with the parted tail. And it had come to find us, not the other way round! It had made its way along the hedge and then settled down on top of it, bang opposite our seat on the fallen trunk.

‘See if it’s hungry!’ Jim hissed. ‘Get one of those nuts out!’

I stood up and moved slowly down the path. The squirrel didn’t bat an eyelid, but just watched me as I popped the shiny hazelnut down on a mossy log a little way along. Jim had identified it earlier as a decent spot for a snap.

In a gingery flash the squirrel was there.

Jim shot picture after picture, and pretty soon four nuts were down to just the one.

‘Go on!’

Crouching down, I positioned the last of the nuts. Jim was laughing. ‘What?’ I asked. ‘You’ve got your own squirrel!’ he told me.

It is perhaps due to the red squirrels’ frequent encounters with nature-lovers in this location that these creatures of rare status have become accustomed to people. We’d gone in search of them, but they had found us – that first red we’d encountered – remember, a wild animal – had run straight towards Jim’s lens without even a second thought.

We walked back to the van in silence for our drive to the ferry port. Surrounded by birdsong, our squirrel safari replaying in our heads, we hadn’t needed words.

On our arrival home I popped outside to top up our bird feeders. This ugly sight met my eyes:

Back inside, I complained to Jim. ‘It’s still at it!’

’Who? What?’

’The squirrel!’

The colonisation of the UK mainland by grey squirrels since the nineteenth century has been remarkable, and it’s nice to have a variety of animal visitors to the garden. But Reader, I’d love to see some more of the red ones.

Love,

Rebecca

If you’ve enjoyed this post, do please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

Dear Reader, do remember to check out Medha’s work! Here you go!

Oh gosh, have I got a treat for you?! 🥳

The fabulous Medha Murtagh of 'Great Things' - https://greatthings.substack.com - has sent me a cartoon of my squirrel encounter, which I've added to my post for you to enjoy.

Thank you, Medha - I'm beyond thrilled! ♥️⭐️🐿️⭐️♥️

yup, I’ll confess to a little gray squirrel watching myself ... and to trying to foil them from getting after the bird seed, the little bastards