Dear Reader,

My visitor experience at a museum is, to a certain degree, designed for me by its curators and collections managers, but I wonder if in simply following a specific path I am missing my opportunity for my own unique journey through the exhibits? I want to pick a selection from the buffet, not be served a plate from the pass.

Never mind the signs to guide me through an exhibition’s layout, the waymarking of the space or the feeling that I should consider every interpretation board to be required reading; for me the best kind of museum visit gives me the opportunity to find for myself those elements of its subject matter which relate directly to my interests.

At the Louvre on a school trip as a teenager I stopped in my tracks on my way to see the Mona Lisa in favour of examining for ages a painting of the Eiffel Tower instead: artwork I recognised as the exact image on the cover of my French textbook. I had nothing in common with da Vinci’s enigmatic Giaconda, but I could relate what I was seeing to the book I knew so well from my language classes. When asked later what my favourite exhibit at the world-famous gallery had been, ‘that textbook picture’ had been my answer.

And on the subject of textbooks, do I need to have done my homework before I visit a museum? In fact, are there advantages to my approaching one entirely tabula rasa1; without the risk of any prior knowledge influencing my experience of engaging with the material? Keeping an open mind will surely work in my favour. 🤔

As it happens I had known very little about Rev Gilbert White until my recent visit to his house at Selborne, Hampshire, now a museum showing the life and work of this eighteenth century naturalist and ecologist often referred to as ‘the David Attenborough of his day’.

White’s book The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne was published in 1789, four years before his death. Since that time it has never been out of print, and is reported to be one of the most published books in the English language.

Taken from the website of Gilbert White’s House.

With no – or at least very little – knowledge about White and his work I began to walk through the series of exhibition rooms with an entirely open mind, but soon found my own passions steering my route.

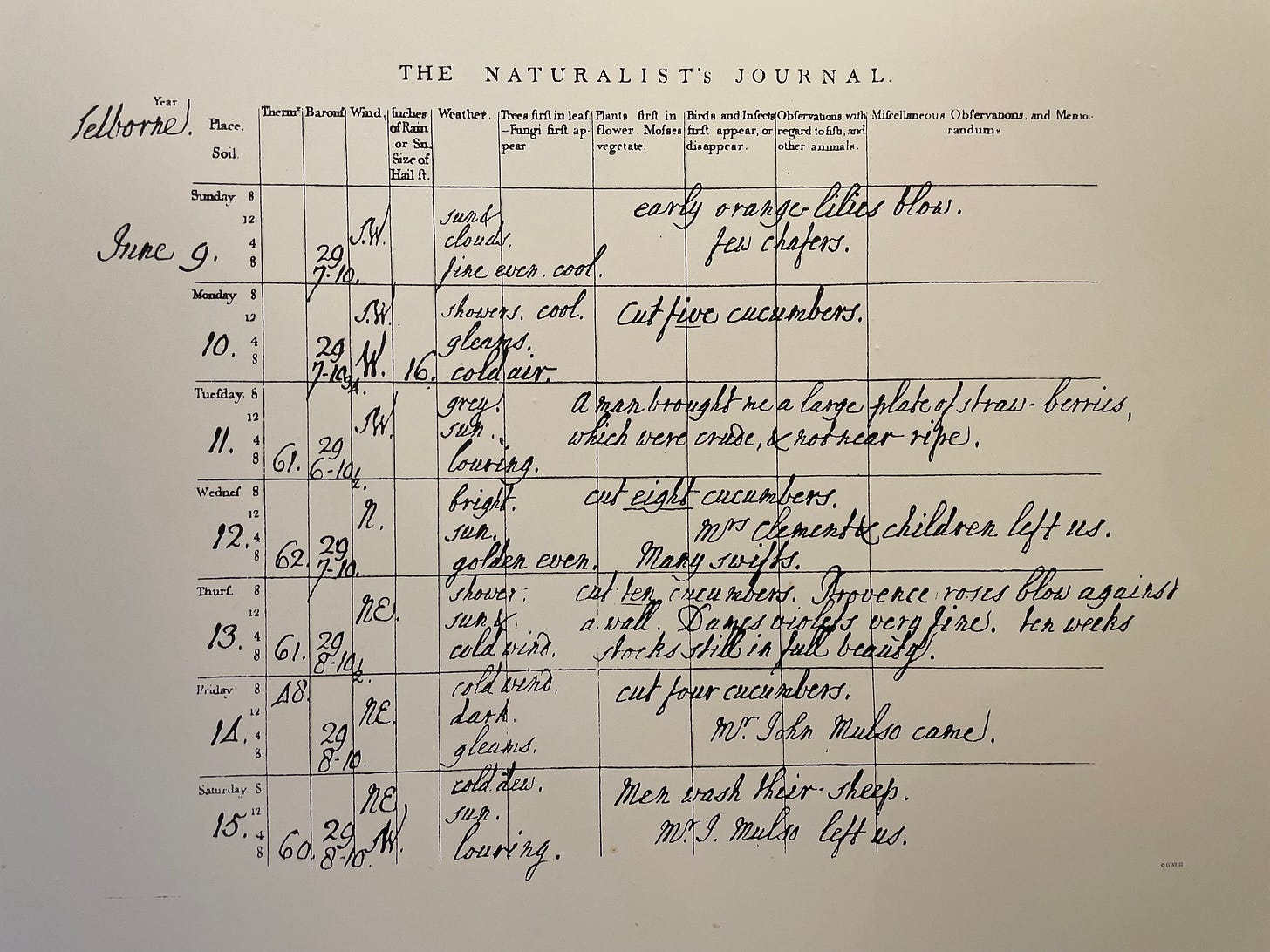

As an avid journal-keeper myself I was fascinated by White’s notes on his own garden, nature and the progress of the seasons.

The Garden Kalendar

Between 1751 and 1771 Gilbert kept a detailed record of all the work in the gardens… tracking the weather and growth of plants.The Naturalist’s Journal

Gilbert’s publisher brother, Benjamin, first encouraged him to record his observations using Barrington’s Naturalist Journal. The Journal had printed columns for the date, temperature, air pressure, rain, wind, weather, trees in leaf and plants in flower, animal and other observations. Barrington’s standardised forms enabled biological records from different locations to be compared. Gilbert maintained his Journal until his death in June 1793… He described the work as ‘somewhat of a Natural History of my native parish, an Annus Historio-Naturalis (Natural History Year), comprising a journal for one whole year, and illustrated with large notes and observations.

Text in bold taken from interpretation boards at Gilbert White’s House.

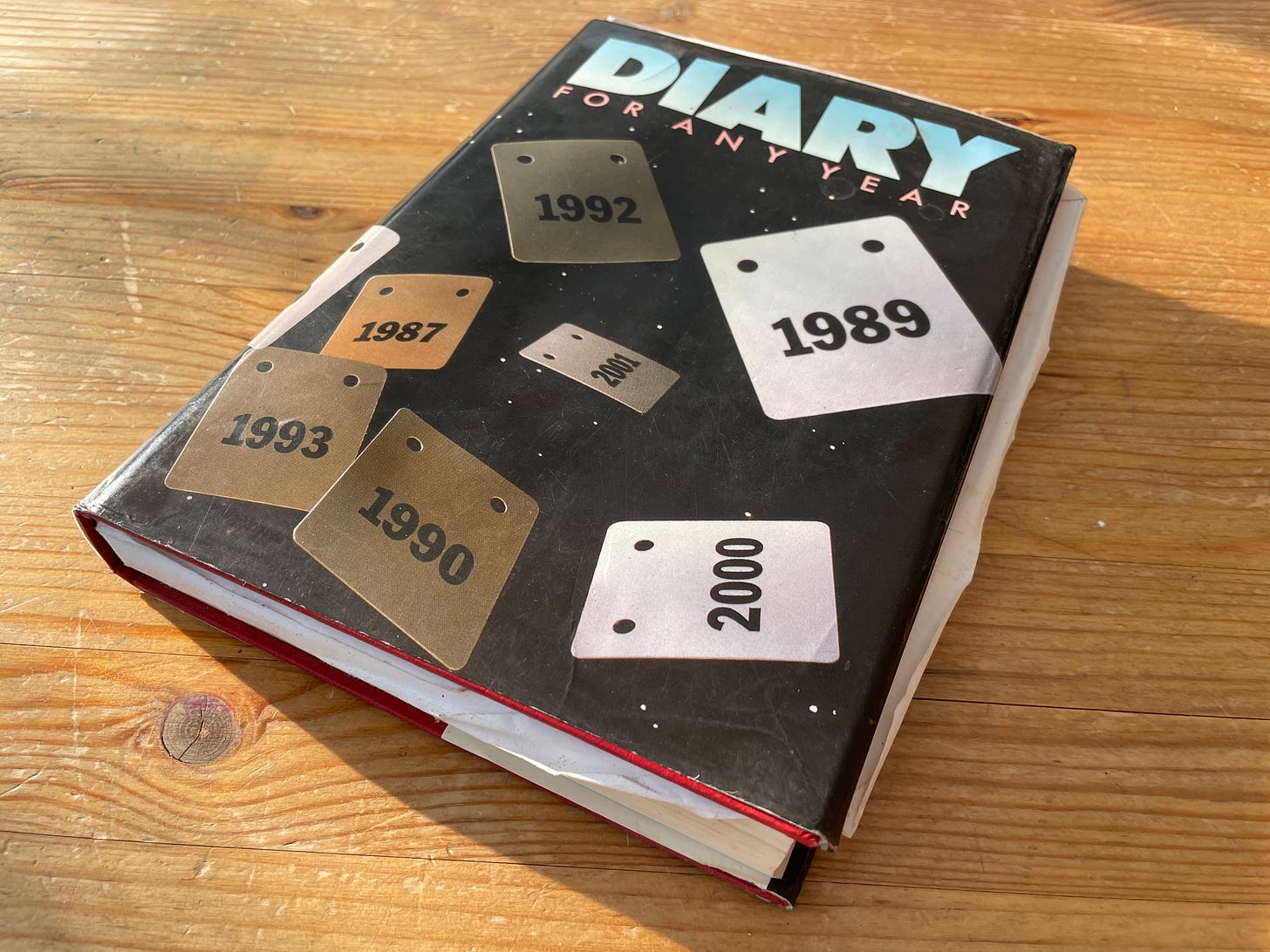

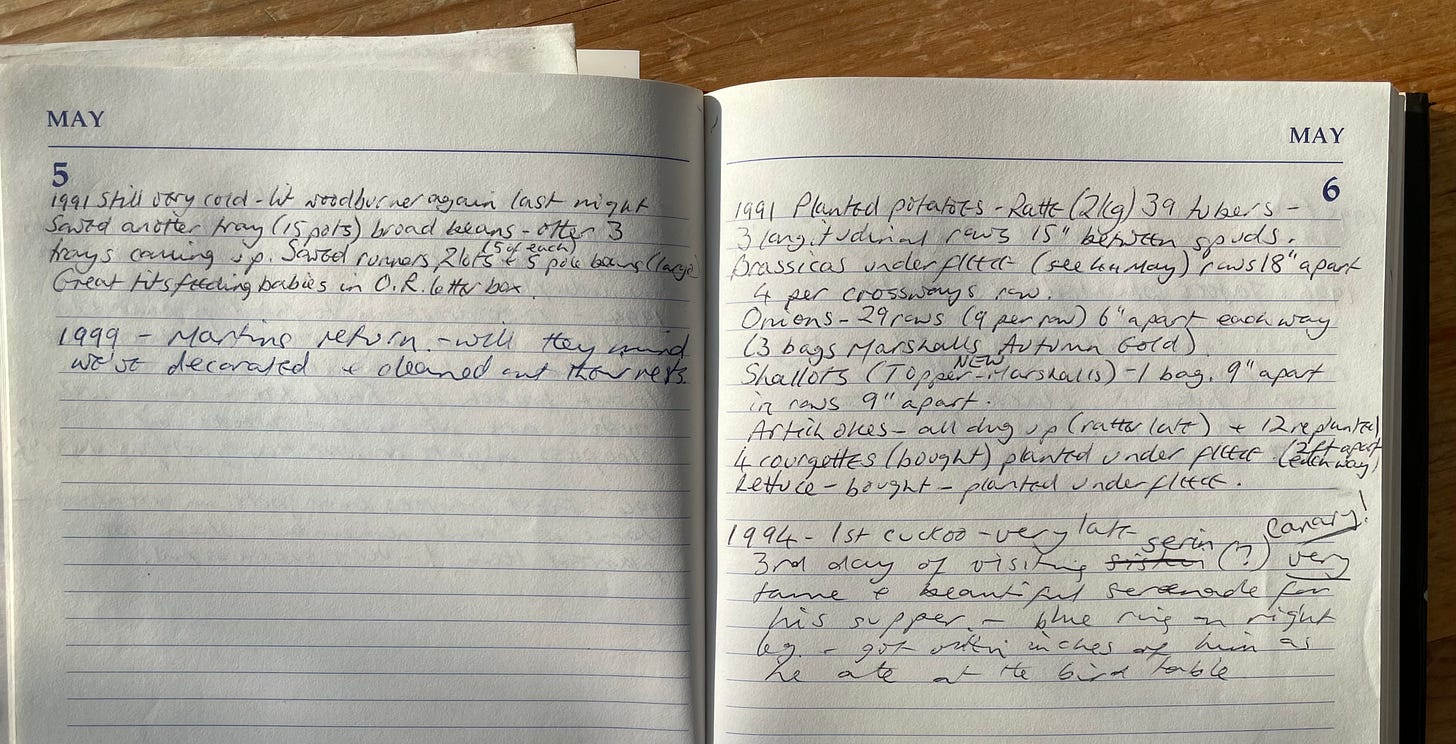

In the early 1990s my parents started keeping a log of their own garden in a diary ‘for any year’ published by Collins. All sorts of things would be recorded; everything from exceptional temperatures and the date on which the potatoes were planted to sightings of particular migratory birds and the success rate of seed germination. This habit of theirs has fallen by the wayside in recent years, but despite having no recent entries the book still fascinates me.

May 3

1992: Found toad has taken up residence in cold frame! Kept awake at night by nightingale.

1995: 3rd very hot day (high 70s). Cuckoo in cool of evening 7.45pm.

1996: Full moon, hard frost!

1998: Cold winds and rain. Potatoes planted – Pentland Javelin + Sharpes Express, 1’ apart.

2008: 2 housemartins home.May 4

1991: 2 swallows on wires in Isfield. Bought 6 Alicante + 2 Gardeners’ Delight, 4 courgettes, 8 Hispi cabbage, 8 cauli + 8 Golden Acre cabbage to grow under fleece.

1994: 1730 drove in to find a pair of nightingales in the garden! Much more green than we’d imagined – male sat on lowest branch of beech tree + sang with gusto. Are we in for weeks of sleepless nights or were they just passing through?!

1994: First potatoes from pots in greenhouse – shame we can’t remember when we planted them! Very successful.June 7

2001: Ground frost! Luckily forewarned by Mollie2 so precious things like Dickson3 wrapped.

Part of Gilbert White’s House is given over to the display of the Oates Collections, and I found the incongruity of showing White’s work alongside that of Frank Oates, explorer of Africa, and Lawrence Oates, member of Captain Scott’s ill-fated Terra Nova Antarctic expedition, to be less of an issue than I’d expected. Two seemingly unrelated museums in one building: I was certainly getting bang for my admission fee buck.

When the home of Gilbert White came up for sale in the 1950s a trust was set up to purchase the house to become a museum. However this was not possible until Robert Washington Oates, a book collector and fan of natural history, came forward. The money was given on the understanding that the museum would commemorate both Gilbert White and the Oates family, principally Frank Oates (1840-1875) and Lawrence Oates (1880-1912).

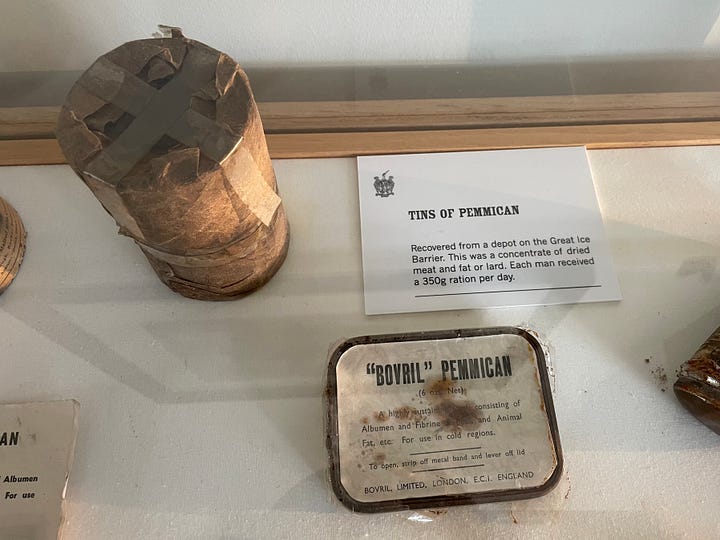

Reminding me of the jar of homemade marmalade dated 1998 which I’d found in my parents’ larder early this year, it was the food items recovered from Captain Scott’s abandoned Antarctic caches which had most caught my attention in the Oates Collections. Reader, I didn’t much fancy the chocolate, but I wondered if the tinned pemmican might still be edible? 🧐

We retired to the café to discuss the risks which any sampling of canned goods over a hundred years old might present, where we were refreshed with coffee and cake of much younger vintage.

Our second museum of the day, Jane Austen’s House at Chawton, was another delight, and again I found myself drawn to the things to which I could most relate.

Being tall and broad of stature I was struck immediately by the diminutive proportions of Austen’s writing table. Any hopes I might have harboured to try her table and chair for size were dashed when I found that both were located behind Perspex barriers, but even at a distance it was clear that this furniture had been made for someone far smaller than me.

We do not know why Jane chose such a tiny table. Perhaps its small, unassuming nature suited her purposes of writing quietly and discreetly. We do know that she wrote on small pages (the Sanditon manuscript measures just 12cm x 19cm) and as a neat worker she could have made do with little space.

Text taken from interpretation board at Jane Austen’s House.

Fair enough, I thought. She wrote on small paper, so she only needed a small table. But what about the scale of Austen herself?

My first clue that Jane Austen might have been built from smaller components than my own came in the next room, where I found the costume worn by Anne Hathaway to portray the author in the 2007 film Becoming Jane.

Then upstairs I found a replica of a pelisse thought to have belonged to Jane Austen herself. Here’s what I learned from the interpretation board:

A pelisse is an overdress or coat dress and would have been fitted closely to the figure. This gives us an indication of how petite Jane was; the pelisse is displayed on a child size mannequin and is a size 4-6 in current UK sizing (size 0-2 US).

‘Petite’ is absolutely right, but the rest of the paragraph was a surprise:

It also indicates that Jane was between 5 feet 6 inches and 5 feet 8 inches tall, very tall for a woman in her time.

As a very tall woman in my time I can relate… although, looking at this picture of myself standing next to Jane’s replica pelisse, can I really…?

Statistics updated just last month show that the average height for a woman in England is 5 feet 5 inches, and in fact, at 6 feet and half an inch I am two and a half inches taller than the average man.

🤣

Keen on art, and having made highly-decorative small-scale 3D objects in my former work as a glass artist, I am drawn to colour, pattern and design, and in this house containing so much fabulous literary heritage I was bowled over next by…

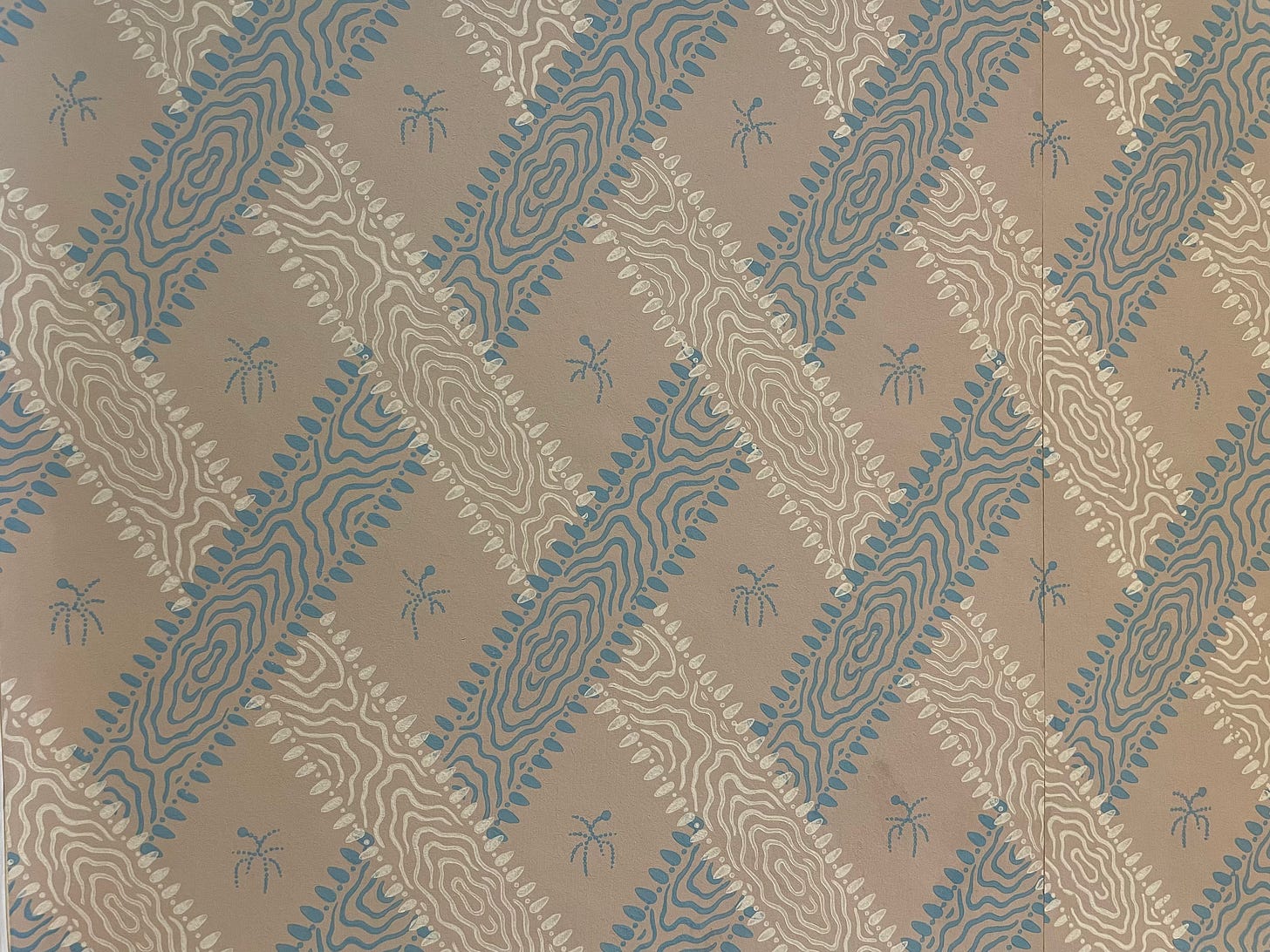

…the wallpaper.

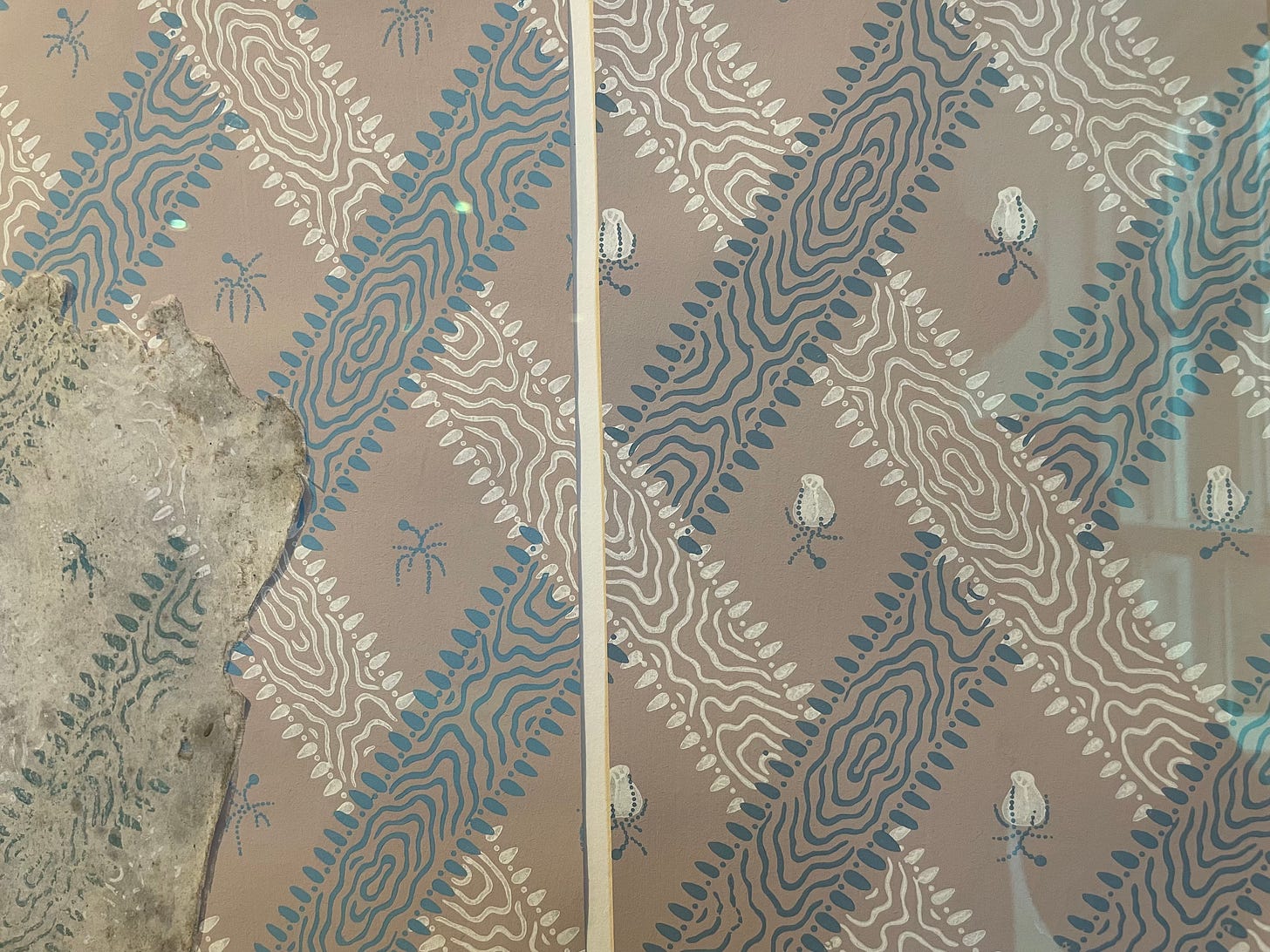

A fragment of ‘Apprentice Ribbon Trellis’ paper dating to 1805 had been found lining the interior of the window shutter boxes in the family room upstairs. I took a close look at the pattern reproduced on the room’s replica paper and couldn’t make out what the curious shape within each rhombus was supposed to depict.

The pattern is made up of blue and white lines, meant to represent ribbons of blue and white silk, interwoven to create a trellis. At the centre of each diamond is an enigmatic ‘pin print’ motif a little like a spider.

Research into the design has shown that this motif was the stem of a rosebud, but in this instance the bud print is missing. This could have occurred if the printer mistakenly printed the blocks in the wrong order. The wallpaper fragments found in the room were hung upside down – possibly to disguise this fact!

We don’t know why the wallpaper is like this. A possible theory is that the Austens purchased the design cheaply as a ‘second’ from the printers, as wallpaper was very expensive and heavily taxed.

Text in bold taken from an interpretation board at Jane Austen’s House.

🔗 You can explore Jane Austen’s house for yourself using the museum website’s fabulous virtual tour.

Of course, my visits to Gilbert White’s House and Jane Austen’s House didn’t give me only things with which I could claim a relationship or which sparked memories – the nature journals, tins of vintage victuals, insight into how very tall I am in comparison to almost anyone else my literary heroine and the opportunity to explore the history and design of nineteenth-century wallpaper – no. Thanks to the attentions of the museums’ curators and staff I could access every part and piece of what had been displayed for me to discover, and enjoyed immensely my experience of both sites.

But Reader, if you were to ask me what my favourite exhibits at those two museums had been, my answer would be that ancient tin of pemmican and Jane Austen’s pelisse.

You see, it is the things to which we best relate which most make their mark.

Love,

Rebecca

📚 Reading 📚

📚 Speaking of being drawn to those museum exhibits which I find most relatable, my top marks for the most relatable post I’ve read this week go to the wonderful

of . If you have autoimmunity (or you don’t), you’re interested in art (or you’re not), or dang, you simply call yourself a human, you’ll certainly enjoy this read:📚 This most recent post from

of contains a beautiful selection of entries from her pillow book. It’s breathtaking.📚 This delicious – and deliciously apolitical – variation on the State of the Union address arrived in my Substack inbox thanks to

of . You will love it:📚 Regular readers of ‘Dear Reader, I’m Lost' will be no strangers to my ongoing light-hearted letter-writing project with fellow Brit

of Eclecticism: Reflections on literature and life. It’s his turn to reply to me on Wednesday! You can find the archive of our chortlesome correspondence here.If you’ve enjoyed this post, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

Tabula rasa is (/ˈtæbjələ ˈrɑːsə/; Latin for "blank slate") is the idea of individuals being born empty of any built-in mental content, so that all knowledge comes from later perceptions or sensory experiences.

Taken from Wikipedia.

Thanks to Terry Freedman for introducing me to the expression.

Grandma.

Dicksonia antarctica (tree fern).

Firstly, thank you so much for your recommendation. I was really touched as I worry about talking about my writing life. I never want to seem as if I'm pushing the barrow.

But to your own essay - to read about your views on museums, open houses and exhibitions, I agree entirely - to wander wherever at one's own pace and focus on the THINGS (that butterfly, the display of blue and white porcelain, the doll's house model of Scott's building in Antarctica, complete with miniature books, notebooks, food supplies etc). I hate following the arrows - ambling is so very important. And huge thank you's for the virtual tours links as well. From way down here, what a privilege to wander so far from home.

Whoa! We're the same height 😃😃