122. Old gold: Lost in a fairytale

A trail of breadcrumbs, and other ineffective aids to navigation.

With so much going on at the moment I’ve dug deep into my archive to bring you an updated version of ‘Lost in a fairytale’, a post which I’d published in March 2023.

When I first starting posting previously-published stories under the ‘Old gold’ badge I had preferred to leave them exactly as they had been at their first outing. On reflection I feel that for the sake of these dusty relics it would be good practice to dig out my refining and burnishing tools in order to bring you a post that is almost as shiny as newly-forged metal.

Thank you for reading!

Rebecca

Dear Reader,

Never mind what else has ever been going on around me, Dad has always encouraged me to do my own thing. ‘Just plough your own furrow’, he tells me still. I think about these words whenever I’m embarking on something new, battling to make progress against the chokehold of worldly expectations, or even trying to find my way home after whichever wrong turn has got me lost this time.

Knowing how difficult I find it to navigate the building, when I’d expressed my intention to pop to the visitors’ loo during a visit to a relative in residential care Jim warned me:

‘Take your breadcrumbs with you.’

I laughed. You see, it’s not just outside that I get lost: I find buildings very confusing. If I’m lucky enough to find where I’m going, I’m often stymied when I turn around to get back to where I’ve started. I don’t recognise layouts or landmarks, and in the care home I don’t seem to register whether the door I’ve passed in that first long corridor is open or closed, despite this being something that I know might help me to recognise my way back.

Wherever I’m going I try to remember to look behind me at intervals to clock a picture of how the return route will look, but the pixels of that image in my brain inevitably scramble and mix themselves up with the ones that represent the route I’m taking there. So, rather than helping me along, my clever technique to view my return journey in advance usually serves only to scupper my outbound one.

Breadcrumbs are a nice analogy, although I’m not sure that leaving an edible trail behind me is entirely practical or desirable. And remember, they didn’t help Hansel and Gretel1.

Yet retracing your steps by following a trail that you’ve left isn’t always a bad idea. Hansel and Gretel had managed to find their way home from a previous outing to the forest by a trail of pebbles; it’s just a shame that the birds had polished off the breadcrumbs the time that it really mattered.

Footprints, of course, leave a literal trail of steps behind us to retrace. We might leave our marks in mud or snow, in wet sand or dry. But there’s no longevity there. If the terrain is soft enough for my boots to leave marks, then other boots – or animal hooves – will do so just as easily right on top of them. Rain can soften a sharp edge to a smudge in a moment; snow can melt, or be covered in more of the same. Impressions in dry desert sand will blow away in just a single breath of the scirocco, and footprints on the beach will last only as long as it takes for the next wave to come in.

(Side note: yes, even I can find my way along a beach and back. Outbound: sea on one side. Return journey: sea on the other. But I know you know what I mean.)

So, what about leaving a physical trail behind? A trail of paper, perhaps? With its alternative name of ‘hare and hounds’ the paperchase was all the rage in post-Victorian Britain.

But like that fairytale breadcrumb trail, the paperchase in E Nesbit’s ‘The Railway Children2’ has its own fair share of peril to captivate young readers.

Bobbie, Peter and Phyllis had been looking forward to watching a paperchase due to take place along the railway line.

They jumped when a voice just behind them panted, “Let me pass, please.” It was the hare—a big-boned, loose-limbed boy, with dark hair lying flat on a very damp forehead. The bag of torn paper under his arm was fastened across one shoulder by a strap. The children stood back. The hare ran along the line, and the workmen leaned on their picks to watch him. He ran on steadily and disappeared into the mouth of the tunnel.

And now, following the track of the hare by the little white blots of scattered paper, came the hounds. There were thirty of them, and they all came down the steep, ladder-like steps by ones and twos and threes and sixes and sevens. Bobbie and Phyllis and Peter counted them as they passed. The foremost ones hesitated a moment at the foot of the ladder, then their eyes caught the gleam of scattered whiteness along the line and they turned towards the tunnel, and, by ones and twos and threes and sixes and sevens, disappeared in the dark mouth of it. The last one, in a red jersey, seemed to be extinguished by the darkness like a candle that is blown out.

Taken from ‘The Railway Children’ by E Nesbit.

Can hare and hounds be a one-player game? As a solo walker could I be the hare on the way out and the hounds on the way back? And if I leave a trail of paper behind me on an out-and-back walk, would it even stick around for long enough for me to follow it home and collect the pieces as I go? The wind might blow it away, or what if a gang of community-minded litter pickers were to happen to be following me? I’d be lost in a flash.

Reader, no. Rebecca is not a litterbug. 🙄

Let me remind you what I’m up against. When I’m out in the wilds I get into all sorts of tangles. Often lulled into a false sense of security by following a straight path for long enough to render me geographically fearless, moments of gung-ho I-can-do-this confidence can easily lead me astray.

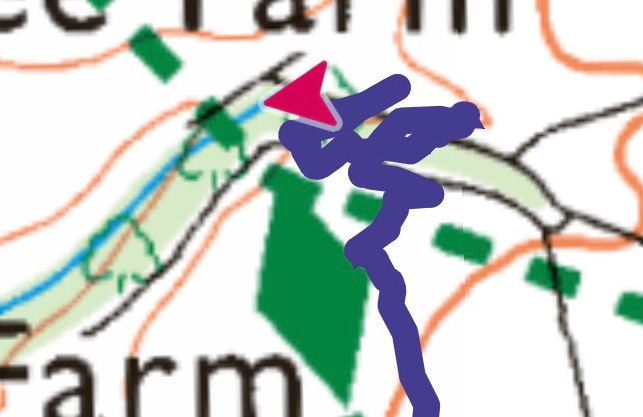

Take this GPS evidence of one of my navigation disasters. I hesitate to even use the ‘Record Activity’ function on the OS Maps app any more:

You can read my sorry tale of creating this navigation spaghetti here:

My routes are clearly scrambled: my brain is a tangled mess. Yet ancient mythology’s idea of a string-based navigation tool, Ariadne’s thread, is no help. I mean, giving your Greek hero a long line to unravel on his way in to the labyrinth might be a fine approach towards ensuring that he later makes it out again and into your Hellenic arms, but the thread itself is problematic.

I’ve got a ball of wool around here somewhere. Yet as an accident-prone navigational knitter I would surely tie myself in knots hopping over stiles, and what would happen when an out-and-back route becomes a circular one thanks to my profound inability to stick to the plan I’d set out with?

Well, the landscape would pretty soon be wrapped in a choking scarf of yarn.

There are so many ways – many more than just the four I’ve explored in this post – that I could use to help me retrace my steps on an out-and-back walk, even if that walk is just a trip down the corridor to the visitors’ loo in my relative’s care home.

But there are certainly pitfalls to the four I’ve explored here:

As Hansel and Gretel would testify, breadcrumbs are simply too good a lunch for the birds.

Footprints in mud, snow and sand don’t last long.

Scraps of paper are at risk of being blown away or cleared up by members of the community more responsible for the environment than the litterbug in size-nine boots sprinkling confetti behind her.

I can’t think of many tools more impractical than a ball of string to take on a walk, unless I encounter the kind of emergency that would require me to darn one of my hiking socks while I’m still out on the trail3.

And wouldn’t it be so much nicer if I could just steer myself? Reader, I need to learn to find my own way. Plough my own furrow, just as Dad has always told me to do.

There’s clearly just one thing for it. If one day you come across a six-foot solo walker striding out along the scenic walks of Sussex towing a tiny plough behind her, do give her a wave.

I promise to wave back before I turn to follow my furrow home. Thanks, Dad.

Love,

Rebecca

📚 Reading 📚

📚

provides one of my favourite punctuation points of the week. In her latest edition details her art process, which this time features one of my favourite animals. 🦒 Although as such a tall girl I had always identified with giraffes, until I saw one in the wild I had imagined them as ungainly. I was wrong: they are such graceful creatures.📚 Regular readers of ‘Dear Reader, I’m Lost' will be no strangers to my ongoing light-hearted correspondence with fellow Brit Terry Freedman of Eclecticism: Reflections on literature and life. It’s my turn to write to him on Wednesday!

If you’ve enjoyed this post, do please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

https://www.science.smith.edu/climatelit/hansel-and-gretel/

The Railway Children is a children's book by Edith Nesbit, originally serialised in The London Magazine during 1905 and published in book form in the same year.

(Taken from Wikipedia.)

You’ll be pleased to know that I’ve just added the words ‘darning needle’ to my rucksack kit list. #beprepared

Did you ever watch the TV series, The Americans? https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2149175/. We noticed in the series that if a character was rummaging around for something in a place that character shouldn't be, a photo was taken before the rummaging so the rummager could put everything back the way it was. Have you tried taking photos of landmarks or even just what you see in front of you, or behind you, so that the way to and from, might be more manageable? Just an idea. That might be a lot of swiping, though. . . We used to have a piece of chalk and make marks on tree trunks, fences, rocks, and so on, when exploring the fields and woods of my childhood town. In the fields, we might insert a stick in the ground with a ribbon tied round the top as a "you're on the right way!" marker. There's a movie in your life, Rebecca, and multiple-Oscar-winning movie, full of the best things. 🗺

I would trust you far more than I'd trust the Sat. Nav, Rebecca.

And I have to say, I really love that expression - 'Plough your own furrow'. It's a keeper and I'm writing it in my journal. Haven't heard it for years.