Dear Reader,

Soon after they’d both retired from their cockpit careers with British Airways, Dad and his friend Bob had been discussing whether they should check out the local gliding club.

‘We didn’t miss the airline’, Dad told me, ‘but we wanted to get back in the sky.’

He paused, and then switched from ‘we’ to ‘I’.

‘I wanted to because I missed it.’

Dad had initially been dubious about flying a glider. He’d been piloting powered aircraft for a living since 1968, and had no desire to fly anything without an engine, thanks.

Still, in due course he and Bob had each booked a trial lesson, turning up at the club on the due date armed with a positive mental attitude and looking forward to a return to the sky, even if it was just going to be a one-off.

It wasn’t a one-off. In that single short trip Dad had caught the gliding bug, and was soon enjoying spending time at the club getting to grips with his new passion.

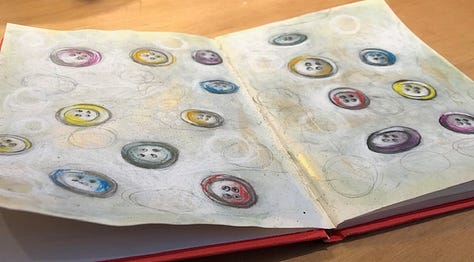

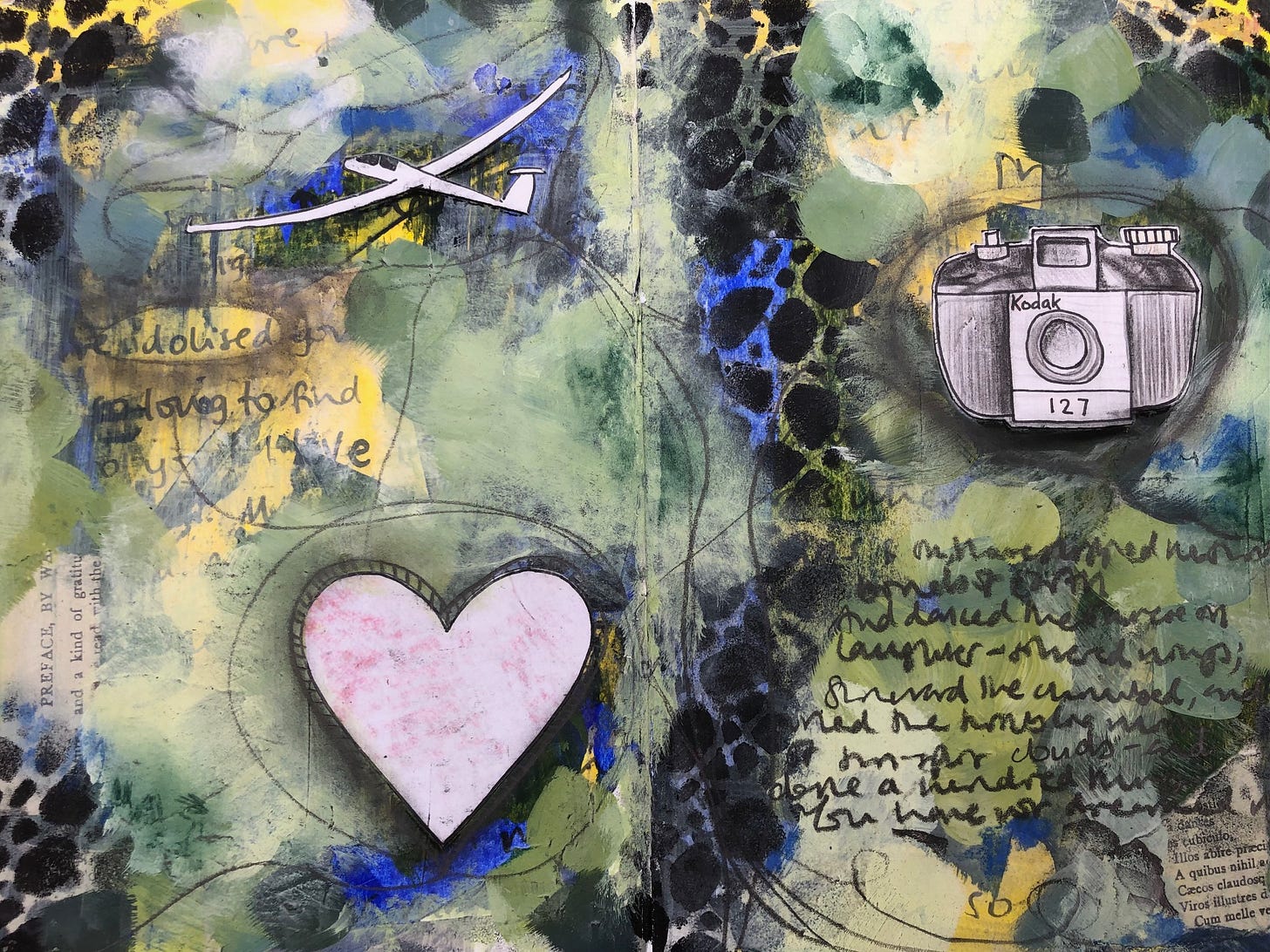

In January 2020 I settled down to make a mixed media art journal spread for the first time. At the time, as a 3D artist working with hot glass, I’d given myself the Christmas gift of a place on Everything Art’s mixed media ‘Wanderlust’ course in an effort to explore making art in a more accessible 2D context.

In her opening lesson in a module entitled ‘Relationships’, teacher Kasia Avery asked students to consider this question:

Which three of my relationships do I treasure the most?

In response I used a permanent marker to free-write my thoughts about my three favourite people, and the irony was not lost on me – both at the time and still now – that much of my creative work has always begun with handwritten words on a page.

I was initially daunted by the steps given in the tutorial, but had no problem choosing the three people on whom I wanted to focus. I chose three symbols, each representing one of my relationships: a glider1, a love heart2 and a camera3.

The very last step of the tutorial for this piece asked me to add a loose outline to each of the three symbols with a pencil, and then to connect them with a thin, scribbly line drawn with my non-dominant hand.

I chose to outline the heart with heavy lines and hatching, then encircling the embellished shape with a simple circle to anchor it more deeply onto the page.

The glider, though, needed movement and life; it needed to soar up and around, the paper cut-out exploring the art spread on the page as well as the sky its tangible self would find itself in.

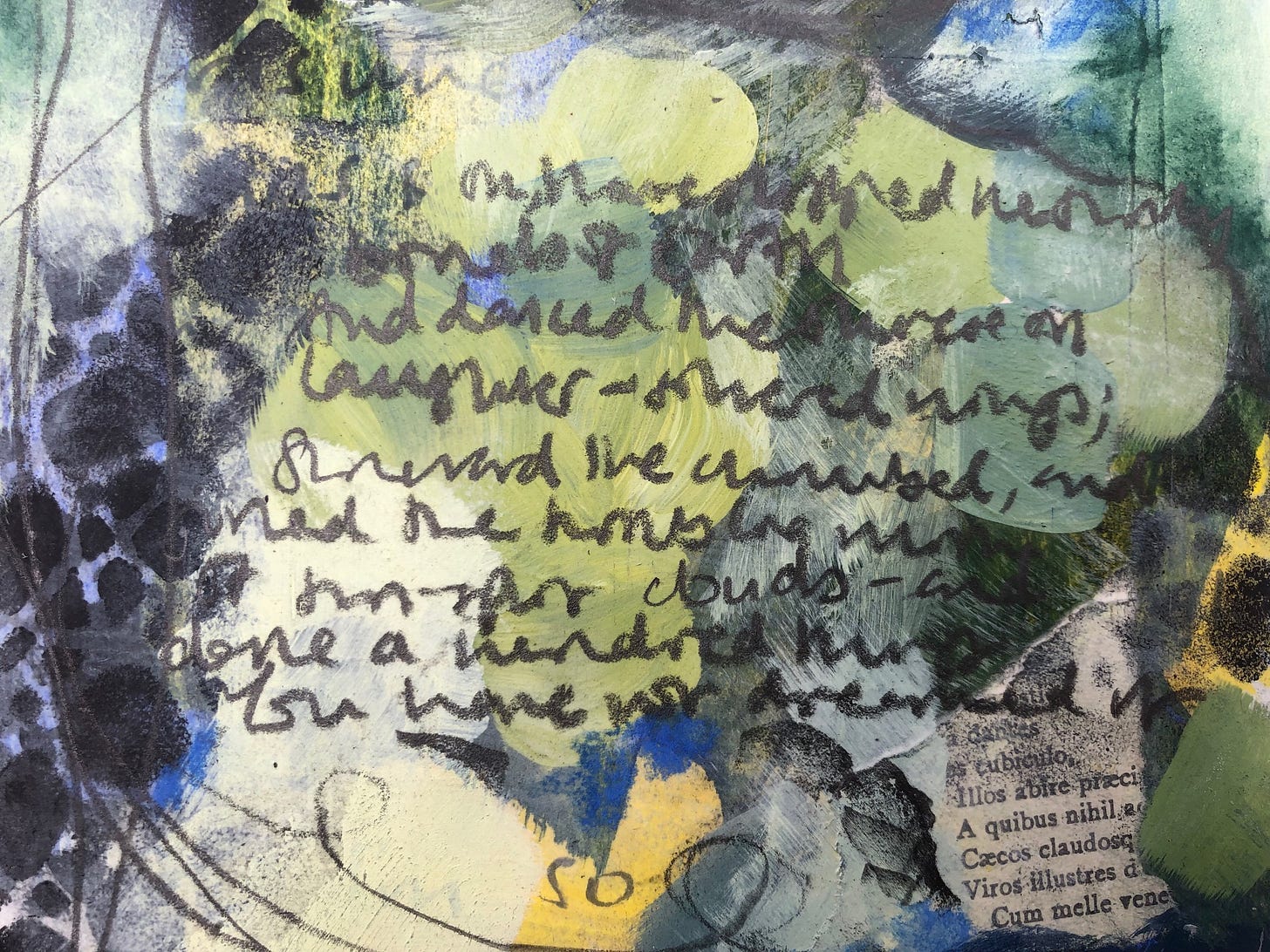

With the bottom right-hand corner of my spread looking rather sparse I suddenly found the words of a poem I knew soaring unexpectedly in my head. I grabbed my pencil again and wrote these lines from ‘High Flight’ by John Gillespie Magee Jr to fill the space:

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds – and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of

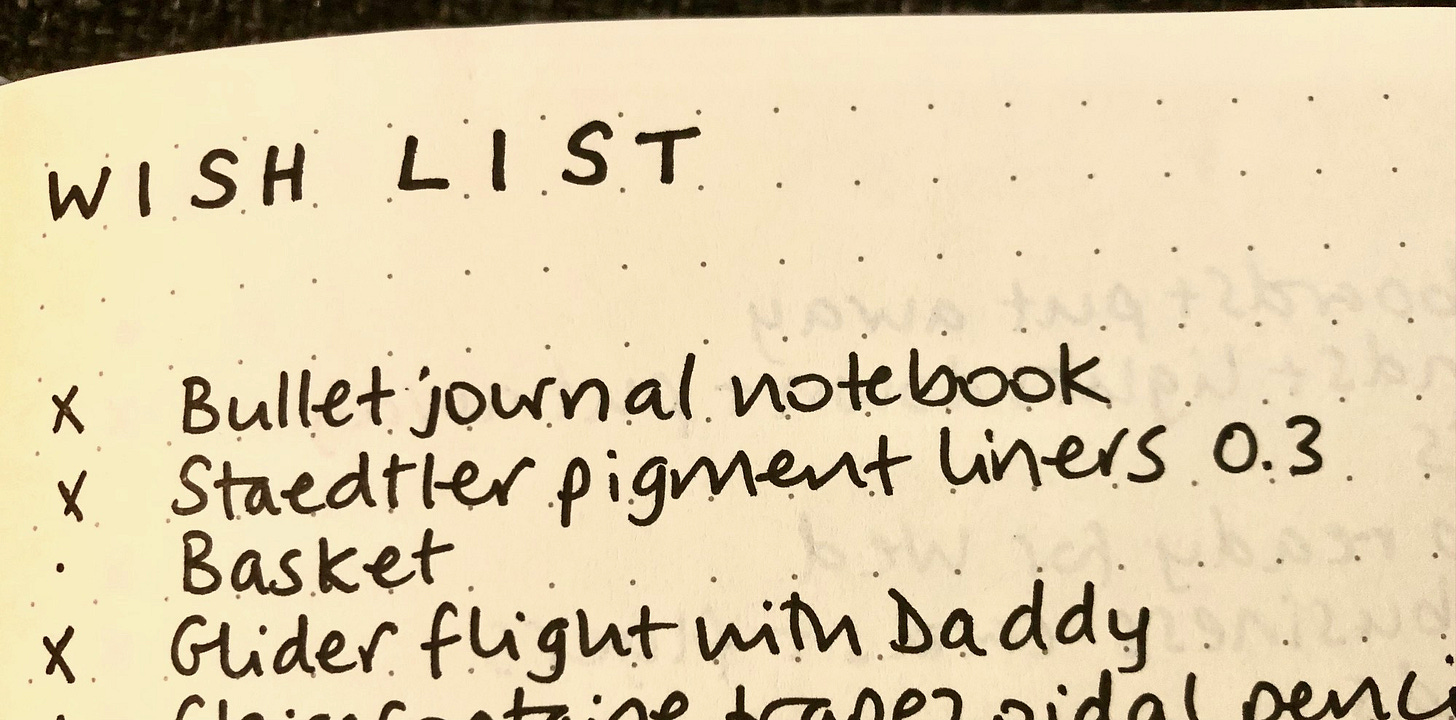

Once Dad had qualified as a gliding instructor – inevitably, really, given his newly-kindled passion for unpowered flight and his long history as a training captain at the airline – something I had dreamed of was to pilot a glider myself under his instruction.

I wondered if I could? In what felt like a rash moment I added this to my wishlist in summer 2019:

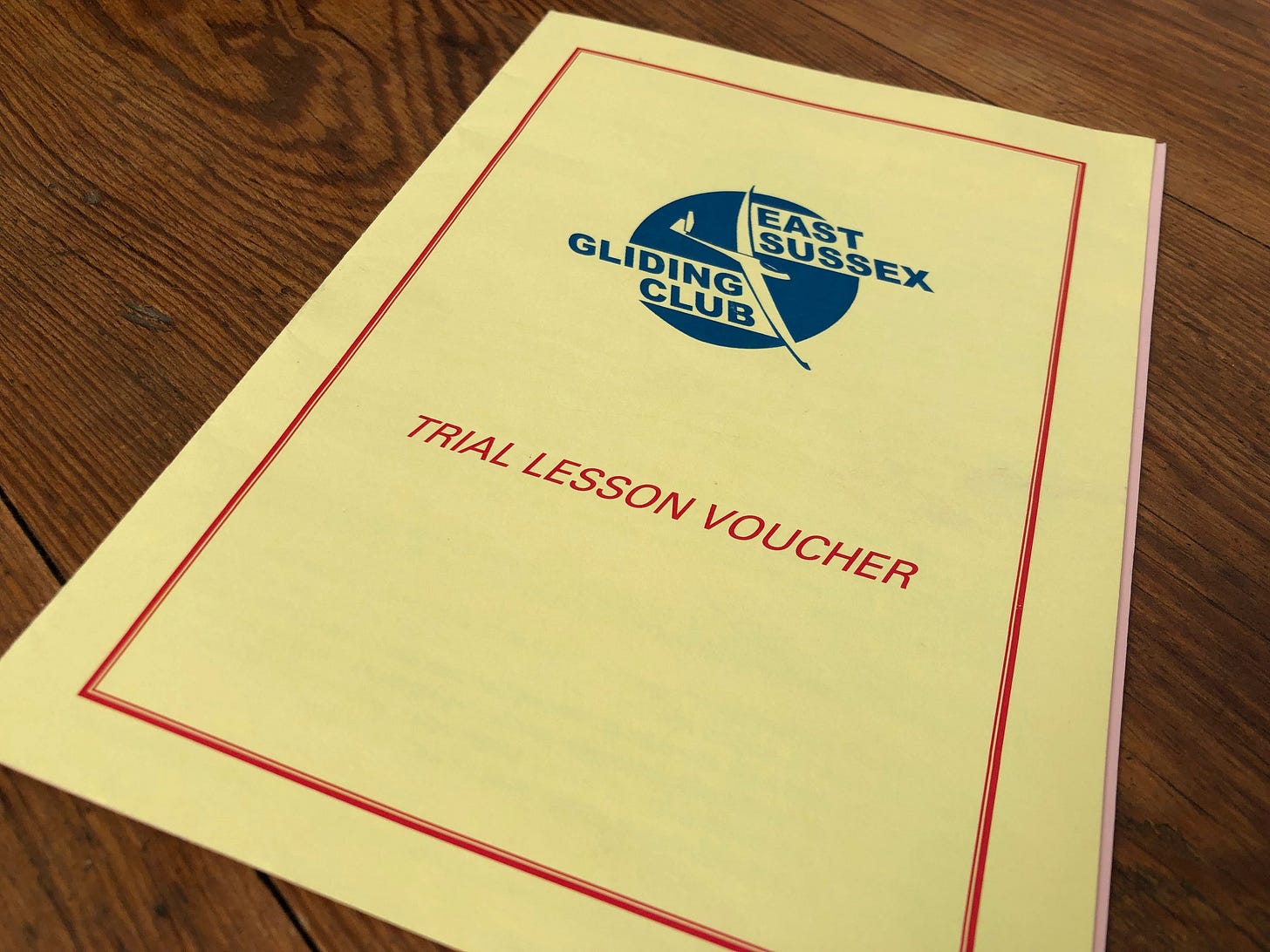

At a family gathering some months later, Dad handed me a slim, stiff parcel. ‘Happy birthday!’ he announced, his eyes twinkling.

Oh gosh.

That had been in late 2019, and what with it being winter, and then with the pandemic putting paid to plans of any kind – not just the special ones like hanging out in the sky with my dad – my voucher stayed in its cardboard envelope.

Then out of the blue last month both Jim and I received this text from Mum:

In the run-up to our trip, I quizzed Dad about what we’d be doing.

First I wanted to know the difference in how it felt to pilot a glider rather than a powered aircraft.

Dad explained that a glider is very small compared to what he’d flown previously – a Boeing 747-400, a heavy, intercontinental jet. Although the size was very different, he told me, a glider flew like anything else, with the same flying controls. He found he was using the same basic skillset to fly a glider as he had for the jumbo, but in a different way because of the size.

‘A heavy jet has powered controls, whereas in a glider the control surface is connected directly to the stick.’

‘If a glider is smaller, then, do you need a lighter touch on the controls?’

‘Not really. They require the same sensitivity, but it is different.’

Dad paused. I asked whether it was like comparing a bicycle to a car with power steering. ‘Good analogy!’ said Dad. On a bike, he explained, there is a direct connection, rather than a system of links and levers. ‘With a glider’, he said, ‘it’s just a piece of wire, which pulls – or rods, which push.’

One difference between flying a glider and flying a heavy jet, Dad told me, was the landing phase, or, more specifically, the approach to landing.

‘Eye height when you land a 747 is 60 feet’, he explained. ‘In a glider, your eye height is just 7 to 8 feet above the ground. It’s a vastly different picture in front of you.’

Wow.

Dad had explained that an essential part of how the club worked was for everyone involved to support each other to make everything happen. All members were experienced in different roles, and were trained to do several jobs.

And when Jim and I rocked up to the club on the appointed day, this was evident immediately.

It had rained heavily that morning, and one chap was busily drying off gliders with a squeegee and a cloth. One was designated time-keeper. The launch controller was overseeing the launches, and an additional crew of two people were ready to assist with every launch: one being responsible for attaching the cable (in the case of both aerotows and winch launches), and the other to keep the glider’s wings level at the launch. In the case of winch launches, the winch driver operates the winch; for aerotows the tug pilot flies the tug aircraft. A tractor driver was towing gliders on the ground, and a retrieve driver was responsible for towing the cable up the field from the winch to any glider about to be winch-launched.

In total, seven people would be needed to get our glider into the air.

We went to find Dad.

‘It might be the case that I’ll be up in the sky with somebody else when it’s your turn,’ he warned me. ‘You don’t have to wait for me – you could go up with another instructor.’

Was he kidding me?

‘Daddy, that’s not really the point. I’d like to go up with you.’

Dad’s friend and club colleague Stephen walked over to us from the control trailer. ‘Right, John, why don’t you go up now? We’re ready, you might as well.’

Reader, we were on!

Stephen looked me straight in the eye, a serious expression on his face. ‘What you need to know is that this is a very dangerous activity’, he told me.

‘Okaaay’, I said, suddenly not quite sure where this was going.

‘Yes. YOU MIGHT GET HOOKED!’ He slapped me on the shoulder, laughing his head off. ‘Enjoy yourselves, both of you!’

Dad lifted the cockpit canopy and began to talk me through the instruments.

‘The thing that hooked me on gliding,’ he told me, ‘is that I had to learn with no automatic aids to assist me. It’s pure flying.’

He explained that flying a glider is all about balance: using all three controls together all of the time. ‘In a jet, we would never have to use the rudder – well, only if you lost an engine – because that was automatic. In a glider we need to take care of the rudder4, elevator5 and aileron6 simultaneously.’

Dad passed me what looked like a rucksack that had been lying on my seat in the front of the glider. ‘Put that on, and do it up here and here,’ he instructed.

Blimey. This was my parachute. 🪂

‘Don’t pull it now, whatever you do, but see that handle? Grasp it. Make sure you know where to find it.’

Once we were in the cockpit – a tight fit, because I’m over 6ft tall with the broadest shoulders you will ever see on a female – Dad showed me where the canopy fastenings were, and the lever that would jettison the canopy itself if we needed to bale out. His repeat of his earlier explanation of what to do with the parachute ended with the words: ‘…and then just look around and enjoy the view.’

‘Dad, honestly!’

Dad told me that we would both have responsibility for looking out for other aircraft.

‘Scan from wing-tip to wing-tip, looking both above and below the horizon, pausing from time to time to focus, and report if you see another aeroplane, using the clock principle.’

‘Clock principle?’

‘Left wing-tip is 9 o’clock, right wing-tip is 3 o’clock. So: 9 o’clock high means far left, above the horizon; 3 o’clock low is far right, below the horizon.’

I nodded.

‘And so on.’

Reader, even I could get to grips with this kind of thing. It was no small relief that he wasn’t asking me to identify north or south. 😉

Sitting relatively comfortably despite the limited space, I followed Dad’s instructions for moving the stick. ‘I’ll be flying’, he told me, ‘but when we’re ready for you to fly I’ll say “You have control”. And then you’ll say…’

I didn’t give him the chance to finish the sentence.

‘I have control!’ I said.

‘Good girl!’

Now that had made me giggle, but I piped down while Dad went through his checklist out loud. This was now all about procedure, and listening to him run through his list made me feel he was speaking to his co-pilot on one of his commercial flights. Reader, I loved this.

The speed of the tug aircraft took me by surprise: one moment we were careering down the airstrip at a rate of knots, the next we were climbing bumpily at a steep angle higher and higher. And gosh, it was noisy – I didn’t know whether that was the tug’s engine, or the surrounding air buffeting the glider itself, but I hadn’t been expecting the clattering ‘whoosh’ that surrounded me.

My cheeks already ached from beaming – I couldn’t help it. And the moment was so intense that my cheeks were wet – I hadn’t realised it at first, but I was crying.

‘THIS IS THE MOST INCREDIBLE THING I HAVE EVER DONE!’ I laughed and yelled at the same time. If Dad replied, I didn’t hear him.

Disengaged from the aerotow at 3,000ft we were out on our own. It was quieter, and I felt more comfortable now we weren’t being pulled at high speed. Reader, we were gliding.

The sky was immense. The rain had cleared, although there was clearly some weather coming from the south-west. Dad radioed to the launch controller with a heads-up. ‘We’ll be okay for a bit’, he told me. ‘That rain’s about ten miles away.’

I spotted a buzzard cruising a thermal a little way beneath us. Flap, flap, flap, gliiide. Flap, flap, flap, gliiide. These impressive birds are immediately identifiable in flight by that pattern, and I loved that we were gliding along with this one.

Dad pointed out various landmarks. ‘Newhaven, Cuckmere Haven, Lewes. Can you see the wind turbine at Glyndebourne? And here we are, over the field again.’

The field, as he called it, was the gliding club. Looking straight down I could see a hive of activity, and watched a glider being pinged up into the sky by the ground-based winch as if it were a winged ball-bearing in some kind of aviation pinball.

I heard Dad’s voice again.

‘You have control.’

‘I have control.’

This was it! Following Dad’s instructions, with gentle movements of the stick I was now steering the glider. ‘Nose down’ and ‘nose up’ were related to a push forward or a pull back, and I found that moving the stick to the left or to the right would dip the left or right wing down, and the aircraft would bank.

This was amazing!

After a little while Dad took over again. ‘I have control’, he told me. I rested my hands in my lap, and, puffed up with pride at having piloted an aircraft, sat back to enjoy the rest of my flight in Dad’s capable hands.

Having been awed initially simply by the sheer scale of the sky, by the later stages of our flight I had become increasingly fascinated by identifying everything on the ground below us. The landscape looked like a screenshot of Google Earth on steroids: a map in real-world format but with the reassuring accessibility of my maps app.

I hadn’t looked at the sky for minutes, and soon my stomach was knotting up. ‘Concentrate, Rebecca!’ said the voice in my head. ‘It’ll pass.’

Yet the more I admired the view beneath me, the less my stomach enjoyed it.

After a little while I heard my own small voice. ‘Dad, I’m not feeling great.’

‘Okay, lift your head and look at the horizon. Don’t worry, it’s because you’ve been looking down and to the side. You’ll be fine in a sec.’

He was right: in an instant I was already feeling better. I laughed. ‘Wish I’d piped up five minutes ago!’

And now we were approaching the field. Before I knew it the ground was coming up to meet us, and fast. ‘Okay?’ said Dad, and then we were down. I gasped at the speed we were travelling, wheels spinning along the grass, and when we finally stopped it took me a minute to catch my breath.

‘Wow, Dad.’ Those were the only words I could find.

Reader, when it comes to spending time with those important to you, exploring mutual passions with shared experiences or celebrating important relationships on the pages of an art journal, the sky is really not the limit. And that precious time with my dad in the sky, lifted by our own laughter-silvered wings, is a memory I will treasure forever.

Dad, thank you.

Love,

Rebecca

📚 A recent read 📚

Earlier this month

published a terrific post in which she shared her process of painting outside as well as some glorious sky studies. You’ll find the link below. Debbie’s words and her art are both fascinating and beautiful, and those two themes of art and sky are the perfect fit to share alongside my own post this week.If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, the ninth in a monthly series exploring some of my memories in words and pictures, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you! You’ll find all the posts in this ‘Art & Treasures’ series here.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

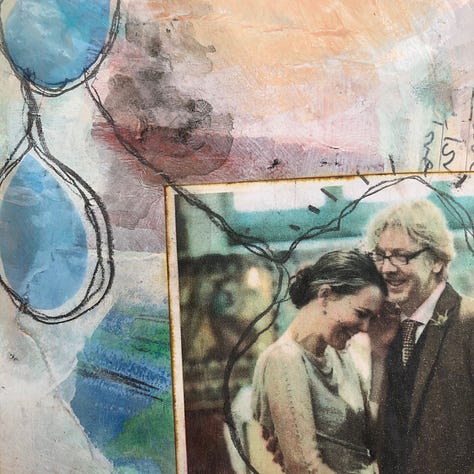

Dad

Mum

Jim

Rudder – operated with pedals. Makes the aircraft yaw.

Elevator – operated with the stick (control column) with a forwards or backwards motion. Makes the aircraft pitch down or pitch up, respectively.

Aileron – operated with the stick (control column) with a left or right motion. This controls the wings to make the glider bank left or right.

As a father with a 35 year old daughter, I'm guessing that as joyous as this experience was for you, it was equally joyous for your father. And maybe even more so, because it's relatively easy to make our children happy when they're younger, but to share such an experience with your adult child and see how happy you've made them is a special type of parental nirvana.

Thank you for this post. I was smiling while I was reading it.

robertsdavidn.substack.com/about (free)

I could feel my dad's energy with me as I read this. He was learning to fly when he met my mother. He'd wanted to be an astrophysicist but said he wasn't smart enough. When my folks got serious about marriage my mom said she needed him to give up flying. Fifty+ years later he loved sitting in their back yard looking at the clouds and planes in the sky as he lived near an airport. He brought back lots of pictures from clouds on every flight-vacation-trip he ever took. I feel he lost a part of his soul agreeing to that condition. This was a treat! Thank you for sharing it.