68. Which way is the sea?

On always being 90° out. Plus: solstice science, poetry and diagrams!

Dear Reader,

One Saturday last summer we were thrilled to be visiting friends for the first time at their new house at the seaside.

Actually this wasn’t just the first party we’d attended at their house, but at anybody’s since the start of the pandemic two and a half years earlier. 🥳 That this was such a big deal for us perhaps explains why we were late.

After a lovely lunch in the garden of salmon followed by tea-cup trifles (I know this sounds like a party game, but no: these were individual desserts presented in bone-china cups on matching saucers), someone suggested a walk to the beach.

Still sitting at the table, my trifle in delicious progress, I was looking around the garden trying to get my bearings.

Jim wondered what I was doing. ‘What’s up? You’re thinking very hard about something.’

I feigned nonchalance. ‘Just working out where the sea is.’

The others’ ears pricked up. ‘Oh? Which way do you think it is?’

‘That way!’ I pointed with confidence to my left.

‘Nope! It’s over there!’ said at least three of my companions in unison, pointing in the direction I was facing. Jim was laughing, and began to ask me some baffling questions about where the sun was now and where it had been when we had arrived two hours earlier blah blah blah. 🙄

He finished with this:

‘You’re always 90° out!’

I was disappointed, because I’d actually done my homework. I’d been keeping an eye on the SatNav on our way there, and had noticed that the main road on which we’d been driving for the last part of our journey was running east to west. Arriving at the house then, I reckoned it must be near-enough south-facing, and south is where the sea was. ‘Right’, I’d thought, ‘I’ll impress them.’

I’m so naïve. The house wasn’t on that main road, but on a quiet residential cul-de-sac. We’d made several turns to find it, and big-picture-me hadn’t been able to clock any of that finer detail.

(Spoiler: I still made it to the beach. I could see the sea once we’d left the cul-de-sac and made it to the main road.)

I’m very consistent with my 90° out, although I’m around 50/50 with whether it’s plus 90° or minus 90°. To my dubious credit I’m never a whole 180° out, identifying north as south, or east as west – so I can’t be all that bad at this navigation game. 🤔

Or can I?

The sun rises in the east and sets in the west, and this is the one aspect of direction that is ingrained in me. If I’m looking at a gorgeous sunset, I’m looking west. That’s a fact. I know this.

But do I know it? It seems that there are shades of west. Confused by Jim’s repeated attempts to explain it to me, I’ve turned to Google.

The Stanford Solar Center tells me:

The sun only rises due east and sets due west on two days of the year – the spring and fall equinoxes. On other days, the sun rises either north or south of ‘due east’ and sets north or south of ‘due west.’

Each day the rising and setting points change slightly. At the summer solstice, the sun rises as far to the northeast as it ever does, and sets as far to the northwest. Every day after that, the sun rises a tiny bit further south.

At the fall equinox, the sun rises due east and sets due west. It continues on its journey southward until, at the winter solstice, the sun rises as far to the south as it ever does, and sets as far to the southwest.

Reader, I don’t know about you, but I’m exhausted even reading it. I had no idea of this stuff.

Well, actually…

I do know that the iconic prehistoric stone circle at Stonehenge was built to align with the sun on both the summer and winter solstices. So I must have known that the sun doesn’t line up with it on any of the other 363 days of the calendar year. It’s precisely this that shows me deep down that I have at least some awareness of that slight daily change to the rising and setting points of the sun that the Stanford Solar Center describes.

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering dating back some four and a half millennia, and although the true purpose behind the construction of its stone circle has never been established, we do know that its alignment with the sun had been important.

Here’s what English Heritage has to say about this:

On the summer solstice, the sun rises behind the Heel Stone in the north-east part of the horizon and its first rays shine into the heart of Stonehenge. On the winter solstice, the sun sets to the south-west of the stone circle.

Of course, it’s not just ancient British monuments that get to play with sunrise and sunset twice a year. In fact, surely every landmark will hit lit-up perfection with the same regularity? 🤔

Manhattanhenge1, also inaccurately called the Manhattan Solstice, is an event during which the setting sun or the rising sun is aligned with the east–west streets of the main street grid of Manhattan, New York City. The astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has said that he coined the term, by analogy with Stonehenge. The sunsets and sunrises each align twice a year, on dates evenly spaced around the summer solstice and winter solstice. The sunset alignments occur around May 28 and July 13. The sunrise alignments occur around December 5 and January 8.

In accordance with the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, the street grid for most of Manhattan is rotated 29° clockwise from true east-west. Thus, when the azimuth for sunset is 299° (ie 29° north of due west), the sunset aligns with the streets on that grid. This rectilinear grid design runs from north of Houston Street in Lower Manhattan to south of 155th Street (Manhattan) in Upper Manhattan. A more impressive visual spectacle, and the one commonly referred to as Manhattanhenge, occurs a couple of days after the first such date of the year, and a couple of days before the second date, when a pedestrian looking down the centerline of the street westward toward New Jersey can see the full solar disk slightly above the horizon and in between the profiles of the buildings. The date shifts are due to the sunset time being when the last of the sun just disappears below the horizon.

Taken from Wikipedia.

And twice a year in Paris the sun sets in the very centre of the Arc de Triomphe – something which is described on rove.me as “a biannual natural phenomenon that was not planned by the architect of the monument”.

The 90° shift to the workings of my inbuilt compass is a persistent irritation, so I thought I’d take my mind off the issue by using the same shift in an OuLiPo poetry project.

“Ouvroir de littérature potentielle’ (OuLiPo) roughly translates as ‘workshop of potential literature’. The group, which was founded in 1960, defines the term as: “the seeking of new structures and patterns which may be used by writers in any way they enjoy.”

Taken from Wikipedia. Here’s more information from them about OuLiPo, including a list of really fun suggested constraints for you to work with in your own writing.

In my poem, which was inspired by the superb OuLiPo projects of my 'Letters to Terry' Substack collaborator

2, I have removed a typical poetry constraint before imposing my own new ones. So no, it doesn’t (quite) rhyme. 😉It is based on Nikola Tesla’s 1938 translation of an early thirteenth-century poem by French writer Guyot de Provins. Mine is clearly many steps away from both de Provins’ original and Tesla’s translation, but I feel it nevertheless still manages to explain the sailors’ need for a compass for navigation when both moon and stars are obscured. I hope you’ll think so too.

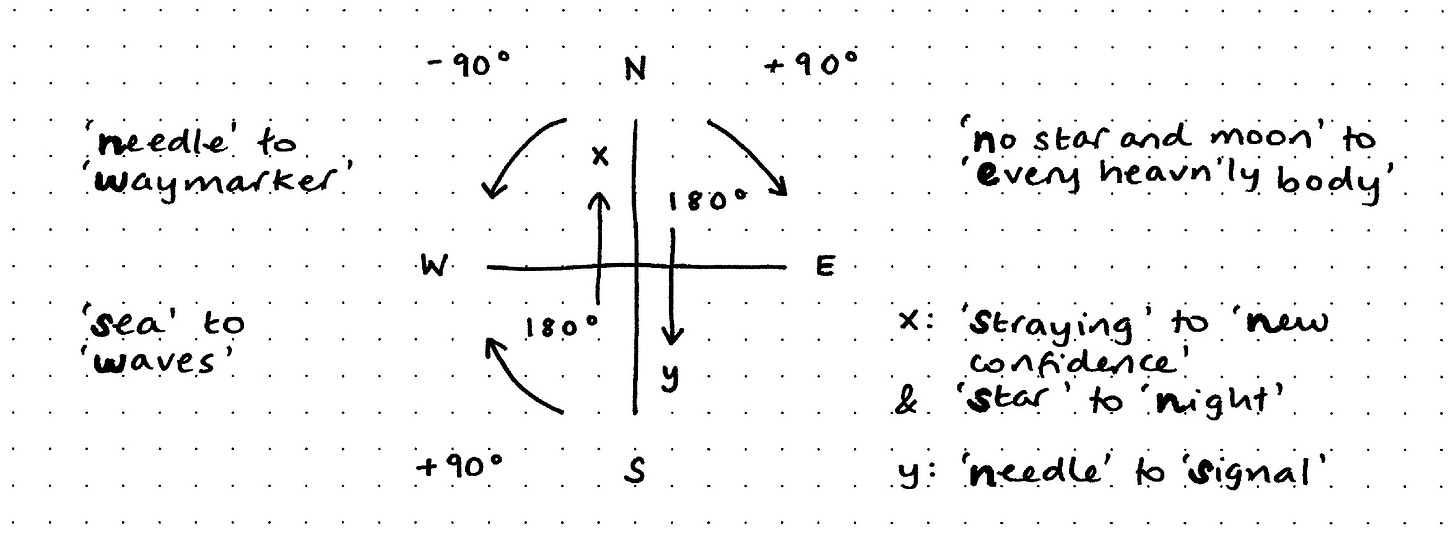

My intention: to apply a ‘90° out’ constraint to Tesla’s translation, substituting appropriate alternatives for words beginning with N for north, S for south, W for west or E for east. Here’s what my compass has made of that challenge:

Tesla’s translation of de Provins’ untitled poem

When gloomy darkness hides the sea

And one no star and moon can see

They turn on the needle the light,

Then from the straying they have no fright

For the needle points to the star.

⭐️

Ninety degrees out, by Rebecca Holden

Now that gloomy darkness veils the waves

And every heav’nly body hides from view

They shine on the waymarker a light:

New confidence against all wayward moves.

That signal leads their way at night.

As you can see from my diagram, the two versions of the poem and my explanation in the footnotes3 a consistent 90° shift isn’t exactly what I achieved, but despite having to alter the criteria I’d initially imposed I’m still pretty pleased with the outcome. 😊

(That’s more than can be said for my solstice reenactment with those wooden game blocks.)

Reader, what have I learned from this exploration of being 90° out?

That writing a poem is hard. (Ditto fun.)

To be surprised that I had to make so many changes in my poem – not just to words, but to the whole mood of it – in order to even play by my self-imposed compass-point rules.

That the very act of setting constraints stretched my verbal boundaries beyond anywhere I had imagined.

That I owe a sideways nod (in whichever direction of the compass) to Terry Freedman, who has kept me guessing all week with this OuLiPuzzle of his own. (And no, I still haven’t solved it.)

And that being 90° out – either on paper, or even geographically – is not necessarily always a disaster. 🤞

With my track record I can well imagine turning up at Stonehenge on the autumn equinox rather than the summer solstice still expecting the first rays of the sun to hit the heart of the iconic stone circle. But no. The sun would be 90° skew-whiff,4 and I'd be exactly three months late to the party. 🥳

Love,

Rebecca

If you’ve enjoyed this post, do please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

Check out my regular Substack collaborator Terry Freedman’s writing around the subject of OuLiPo. Click here to head straight for the OuLiPo section!

Here’s what I did:

Line 1:

‘Sea’ became ‘waves’.

+90° out (a shift from S for south to W for west)

Line 2:

The phrase ‘no star and moon can see’ became ‘every heav’nly body hides from view’.

Okay, this one was a big cheat: I treated the whole phrase, not just the word ‘no’, as being led by the letter ‘N’, meaning I allowed myself to get away with an entire line beginning with ‘E’. Shhhh. 😉

+90° out (a shift from N for north to E for east)

Line 3:

‘Needle’ became ‘waymarker’.

-90° out (a shift from N for north to W for west)

Line 4:

I treated all the words from ‘straying’ (where I needed to replace the S for south) until the end of the line as a whole phrase. First I changed the mood of the line from negative to positive, giving me a reason to use the word ‘confidence’. It was easy then to turn my OuLiPo compass 180° by preceding ‘confidence’ with ‘new’.

180° out (a shift from S for south to N for north)

Line 5:

‘Needle’ became ‘signal’.

‘Star’ became ‘night’.

180° out twice (a shift from N for north to S for south, and another from S for south to N for north)

skew-whiff / (ˈskjuːˈwɪf) /

adjective

Informal, British: not straight; askew.

(Taken from Dictionary.com)

The jengahenge pictures are cracking me up . I, too, have this idea that the sun must always rise in the East and set in the west- even though I’ve been to Stonehenge and know that humans built cities , ancient and new, around the movement of the sun. I know science, I scream, get get frustrated when I can’t find where west is based on the sun. A very relatable predicament.

Haven't listened yet. But the poem is a great read! I gave up on Terry's puzzle and I will wait for the key. The first social event for us was very enjoyable, though more nerve wracking than in The Before Times. We'll relearn grace and ease!