Dear Reader,

On one of a series of marketing shoots for the education arm of a national historical organisation we awaited the arrival of our subjects at the Roman fort: a year 4 class of eight and nine-year-olds.

Despite the noise of the buffeting wind we heard them long before we could see them: a high-pitched cacophony of excited children chanting ‘sinister, dexter, sinister, dexter!’ At their village primary school Latin was almost certainly not on the curriculum, but their gleeful repetition of what the Romans called left and right as they marched was an excellent sign that these children were already on board with their visit to these historic ruins.

The kids were in uniform – sort of – to the extent that they were all wearing the same red sweatshirts emblazoned with their school-badge, but in deference to today’s weather forecast there was an assortment of robust, outdoorsy trousers and knee-high wellington boots. One girl was even wearing waterproof trousers: purple ones.

It was chaotic as the children took their time to settle down. The volunteer guide leading the tour was nonplussed when his first ‘Any questions?’ enquiry was met by an awkward, lengthy silence followed by a single small voice asking ‘How old are you?’ Several kids laughed.

‘Why did you ask that?’ asked one of the teachers, embarrassed.

‘I didn’t want him to feel that we didn’t care, Miss, but I couldn’t think of a Roman question!’

Playing along, the guide replied ‘I’m 66!’ He looked pleased when the question-asker revealed that her granddad was ‘MUCH!’ older than that: ‘Like, at least 70!’

I wielded lights while my husband photographed the class in a variety of set-ups, both candid and posed, and once I’d had my fill of listening to the volunteer’s confident patter of instructions, like ‘Have a think about what the Roman soldiers used this sponge on a stick for – I’ll be asking you later’, I found myself looking around the gaggle of children.

There were around thirty in total, divided into four groups, each with its own responsible adult. Some energetic lads from two different groups formed a breakaway gang keen to try to vault over a low wall at the fort, the adults in charge swiftly cutting the boys off in a slick pincer movement before they had the chance to do themselves – or the ancient remains – any damage.

After a while I noticed that one of the adults was missing, and two of the four small groups had merged into one much larger one as a result. I wondered why. Looking around to the far edge of the fort I spotted her sitting on a low wall with the little girl in purple trousers, where she was handing the girl a small Tupperware container and encouraging her to eat its contents.

‘Oh, so that’s why’, I thought. ‘She’s like me. She’s diabetic, and needs a snack.’

The little girl, probably eight years old, had been taken away from the activity by the adult responsible for her, for her wellbeing and safety. This was absolutely the right thing, but I felt really sorry that she was missing out on what her classmates were up to around the fort.

I don’t know how long she’d had diabetes, but right now she was around three years younger than I had been at my own diagnosis. Back then I’d spent two weeks in hospital and then a further two weeks at home, off school, where my family and I tried – on an almost vertical learning curve – to get to grips with dealing with this autoimmune wrecking ball that had entered our lives uninvited.

Back at school for the first time since leaving hospital, and struggling to cope with the enormity of my new life, I had collapsed in (probably hypoglycaemic) tears after just half a day, and my parents came to pick me up. We agreed with the school that I’d attend on a half-day basis for the rest of the week, and then I was on my own.

On my own. No, I wasn’t on my own – not really – my family was amazing, and my teachers and close friends were for the most part understanding and supportive. Yet in some ways I was on my own. I wasn’t supervised: I just got on with things. And sometimes I’d feel strange: thirsty and sick if my blood sugar was high, or dizzy and weak if it was low. I had to eat at regular intervals: I’d never had a routine of eating between meals before I became diabetic, and this new requirement was taking some getting used to. I didn’t really understand it all, and initially I didn’t have an easy way to explain what might be going on with me.

Reader, I didn’t really say anything.

I needed people to know about my condition, but those people needed to be ones with some understanding of what I was going through. I had that at home in spades – did I mention that my family was amazing? – but the people at school just didn’t get it.

They didn’t get that when I flaked out, weak and dizzy, I couldn’t explain myself. If someone found me incoherent in a corner they’d ask me difficult questions, or ask me to weigh up what I thought they felt about what they should do with me. Sweets weren’t allowed at school, so I tried to avoid being seen with glucose tablets, despite being permitted to have them. They weren’t sweets, no, but at the same time they looked like sweets, they were something sweet, and I didn’t want people in my class to be jealous of my access to them, or to resent the fact that I was somehow hideously, inconveniently, excruciatingly special. I did the best I could, but I just wanted to be normal. Ordinary. The old me, not the new, different one. I wanted to be like them. So I would take my hypoglycaemic self off to a corner and not tell anyone I needed help. Or if I was high, I’d excuse myself from class to have yet another wee and drink five minutes’ worth of water straight from the tap, pretending nothing was wrong when I arrived back in the classroom.

When I looked at the little girl in purple trousers being offered a sweet snack on the sidelines, my heart broke. It broke for her, and not just because she was missing the fun of finding out what the Romans used those sponges on sticks for1. But it broke for me, too, because I hadn’t that kind of support from my school when I’d needed it in similar circumstances, aged eleven. For the rest of the day I kept finding her with my eyes, looking to see if she was okay.

Reader, she was fine. Of course she was.

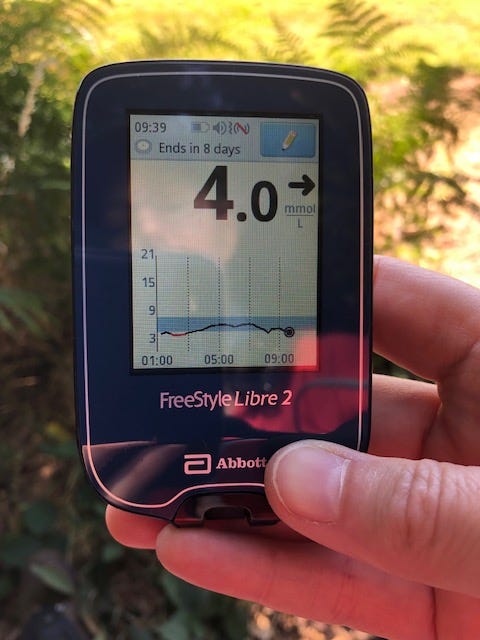

Just as we were saying goodbye and thank you to our class of pint-sized models I heard the faint alarm of my glucose monitor discreetly warning me that I needed to check my levels. Still standing in front of the rabble of small children I leaned my photographic light on its telescopic pole carefully against the wall and fished my monitor out of my pocket. Through my clothes I pressed it against the sensor on my arm.

Low. Thought so.

I noticed the girl in purple trousers looking at me intently as I stowed the monitor and found my glucose tablets. We held each other’s gaze for a moment. Looking straight at her, and smiling, I very deliberately blinked. Hard.

She blinked back, exactly the same. And beamed at me.

Kindred spirits. I knew about her, and now she knew about me. As we turned to leave I noticed her tugging at the coat of her responsible adult, talking to her and pointing shyly at me. Reader, she was singling me out for quiet attention.

I don’t like to be different. I don’t like being singled out or pointed at. But today I didn’t mind, because today I hadn’t been different.

The girl in purple trousers was just like me.

Love,

Rebecca

If you enjoyed this post, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

Wiping, I’m told. I shan’t elaborate. You’re welcome.

This is so lovely. I’m so glad you were able to share a moment with that little girl, and you probably made her life that much easier, in one sweet moment.

This is my new favorite thing you've written. Such heart. Thank you.