In which Rebecca examines a book which has journeyed over four thousand miles and back to very close to the place it had been written.

Dear Reader,

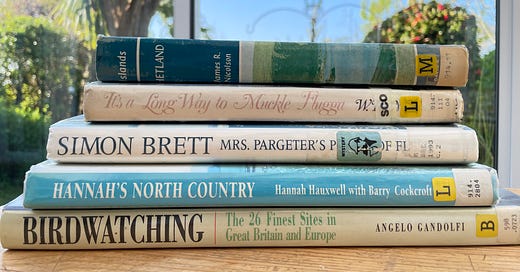

I’d never read any novels by prolific British author Simon Brett, but I had grown up consuming an entertaining diet of sitcoms he’d written. My post-school, pre-homework 6.30pm listening had generally been one of his comedy dramas like After Henry or Smelling of Roses on BBC Radio 4. Knowing Brett to be resident in the same area in which I found myself camping a few weeks ago, I was pleased to find this book on the shelf of secondhand books next to the campsite’s reception desk:

It hadn’t been only the author’s name on the spine which had piqued my interest, though; my eye had also been drawn to this sticker:

The illustration beneath the word ‘Mystery’ is an absolute hoot – a graphic representation of Sherlock Holmes, complete with deerstalker hat, a Meerschaum pipe bigger than his face, and an improbably-large moustache.

🕵🏻♂️

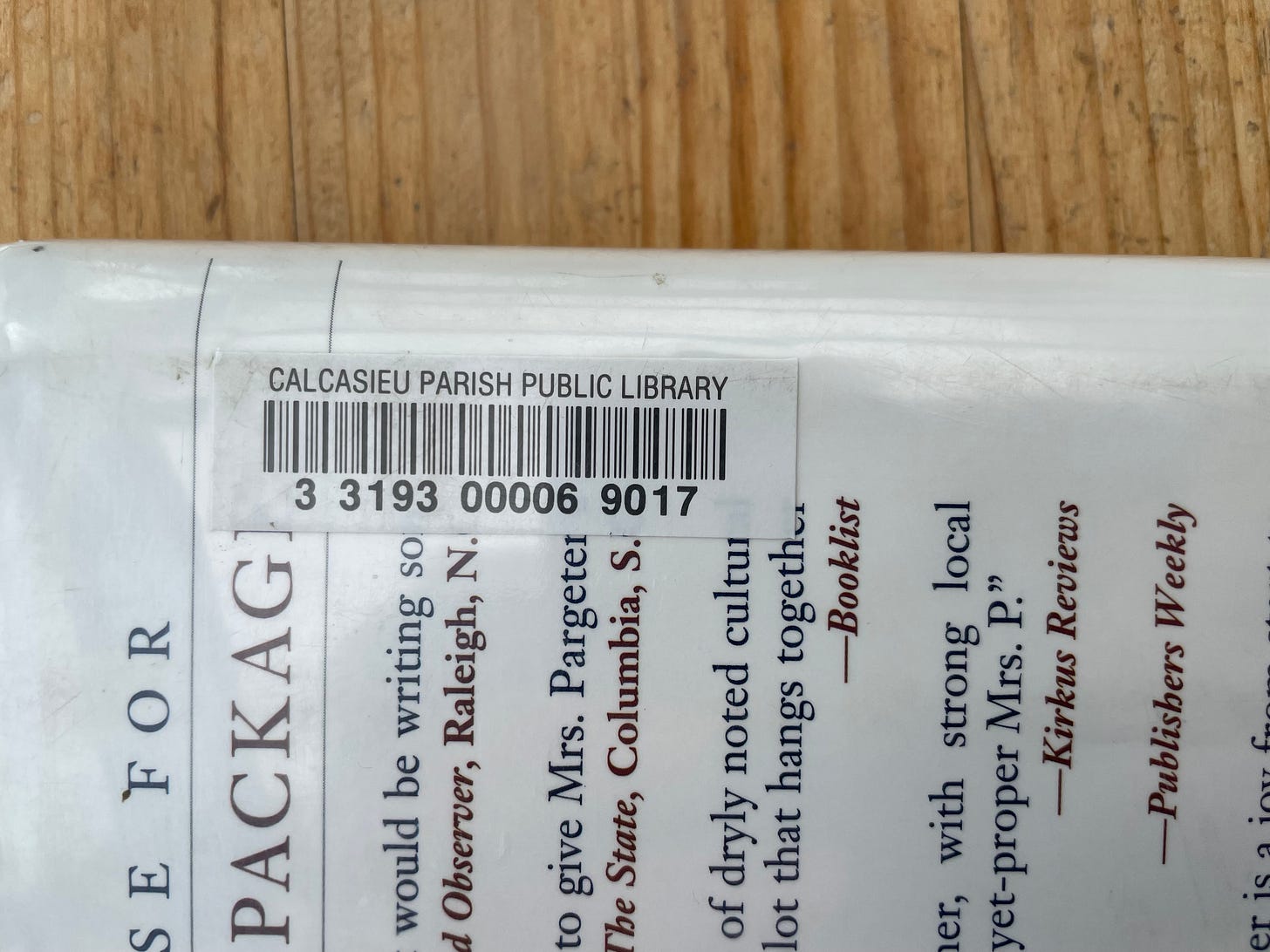

Reader, this book clearly used to belong to a library, and it was an unfamiliar place name which revealed itself when I turned the volume over. Now, I can’t claim to know the name of every location in the United Kingdom, and my aptitude for geography is, as you know, utterly absent, but I was pretty sure that Calcasieu was nowhere near these shores.

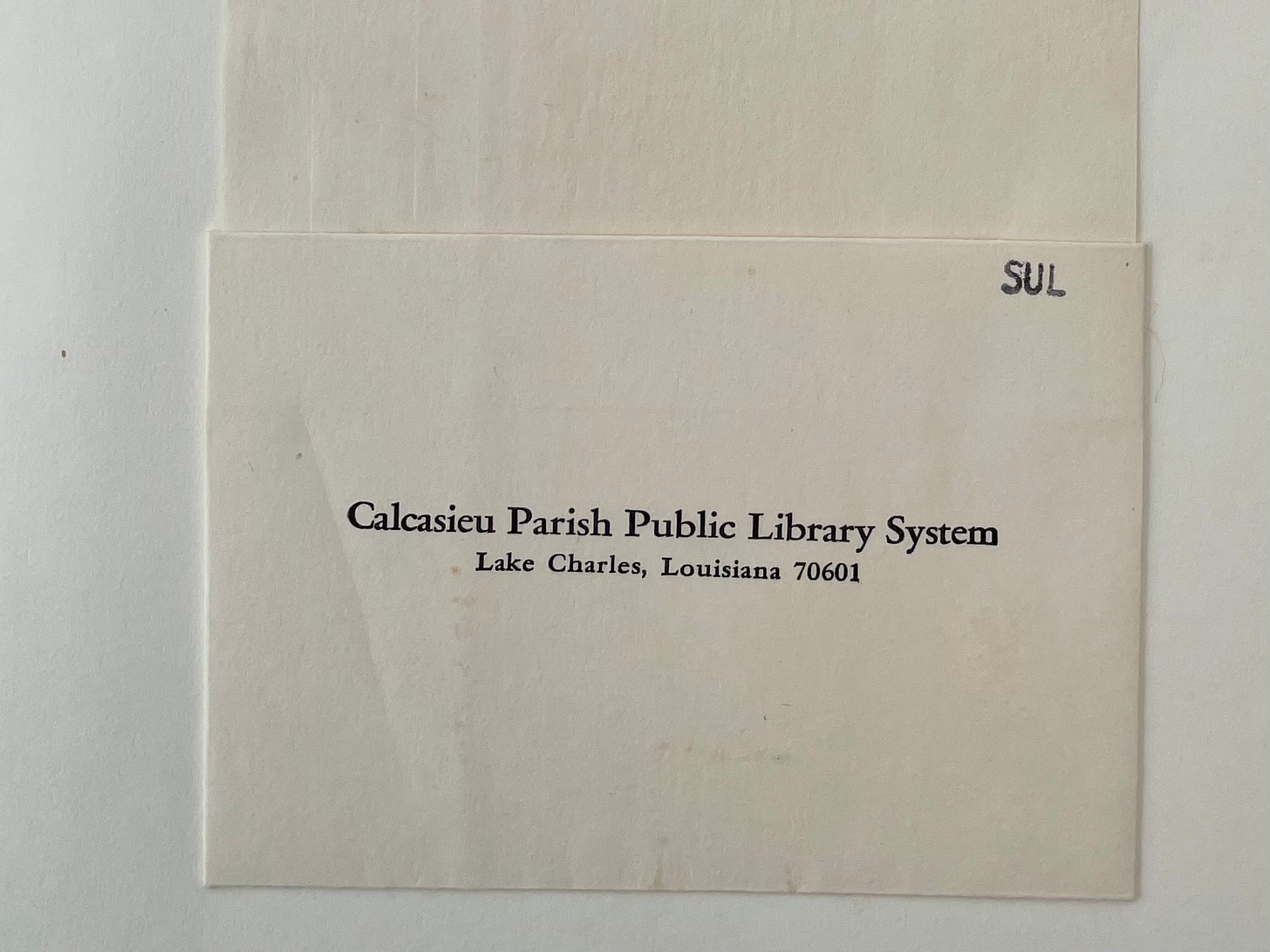

Where is Calcasieu Parish? I found the answer inside, on a label intended for a cataloguing card to be stowed: Lake Charles, Louisiana 70601.

Calcasieu Parish Library offers fantastic collections, resources and programs.

Do have a look!

Any fears I had that any fines remained owing by the last borrower of the book were assuaged when I spotted the rubberstamped words WITHDRAWN FROM LIBRARY COLLECTION on one of its first pages.

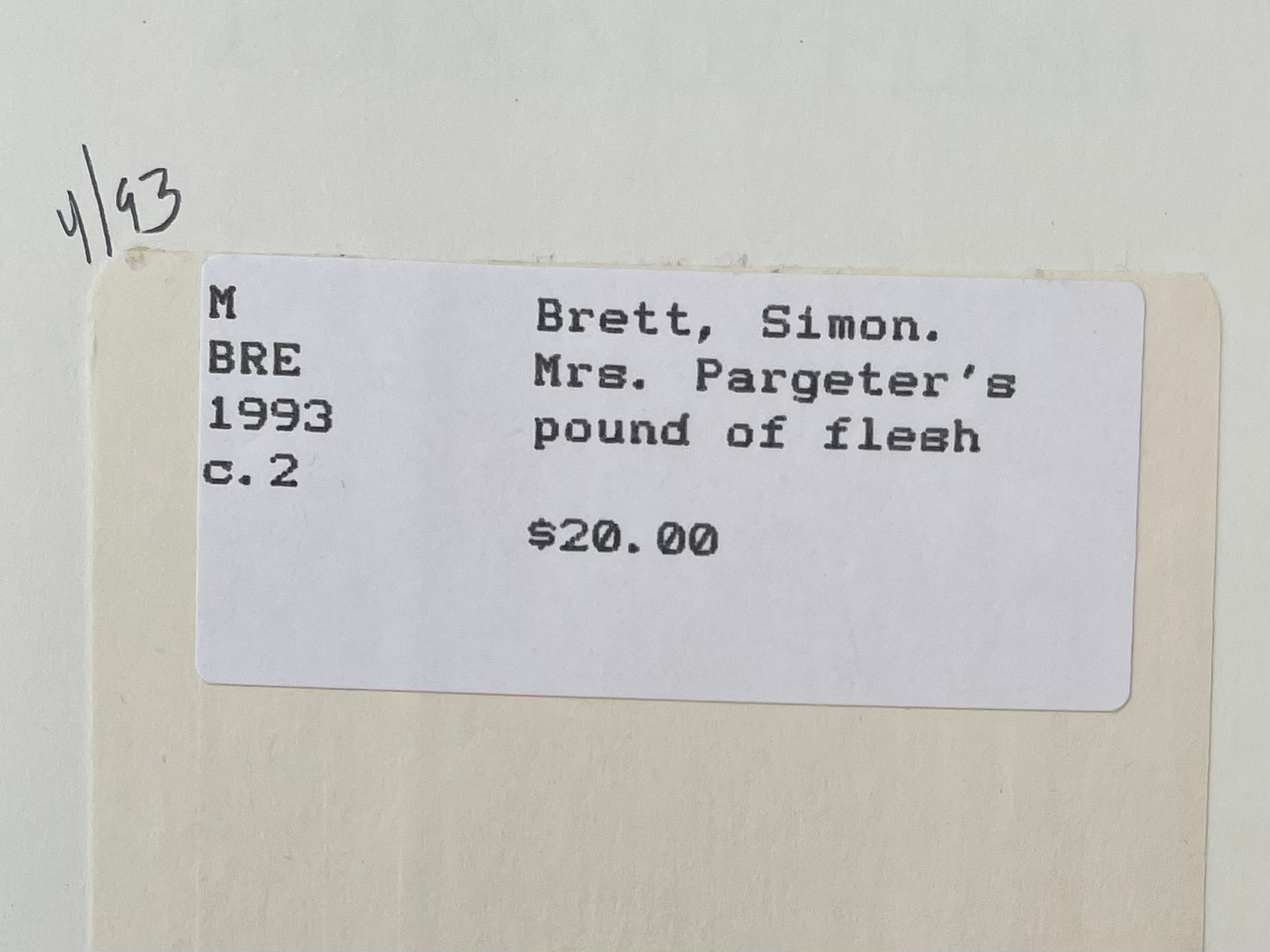

I found the ‘c. 2’ notation interesting: perhaps it means ‘copy 2’ of the volumes of this novel found in Calcasieu Parish? Is it realistic, though, to expect one community library to have two copies of its own? Well, maybe. 🤔 And 9/93 represents, I’m certain, the month in which the library had acquired the book, which would fit very nicely with the publication date of the US edition having been 1993.

It’s interesting that the book’s purchase price had been noted on the library label. I wonder why this is necessary, given that the list price for the volume is printed on the inner flap of the dust jacket. Still, the place the publishers choose to print their list price might of course vary from book to book, so perhaps adding the price to the library’s own label does make sense. They’ll always know exactly where to find it.

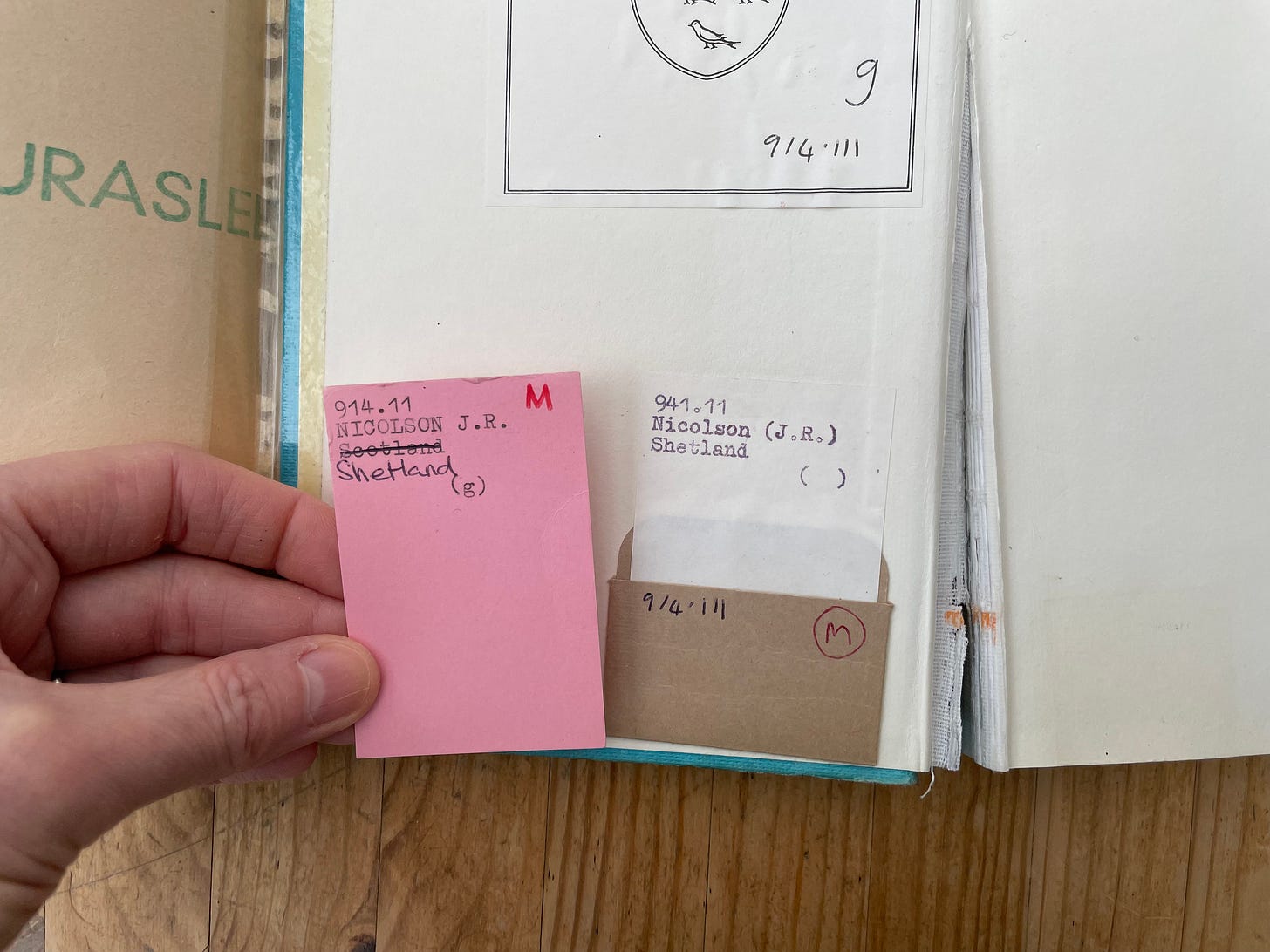

I wondered whether Mrs Pargeter had features in common with books withdrawn from UK libraries, and duly raided the bookshelves of my parents’ home for examples. Turns out they’re similar!

I was thrilled to find that the little insert card for Shetland by James R. Nicolson had made it out of the library still in its cardboard sheath. The fact that the word ‘Scotland’ has been crossed out and ‘Shetland’ added makes me laugh. With the Sussex coast being over 400 miles from the border with Scotland, and over 800 miles from the Shetland Islands, perhaps not everyone around here knows that Shetland is part of Scotland? Hey, never mind!

The insert card is sadly missing from the Louisiana library’s copy of Mrs Pargeter’s Pound of Flesh, but I found the empty sheath extremely useful for housing my bookmark during reading sessions. Hey, why don’t all books come with this nifty little pocket?

British English can be heard loud and clear right from the start of this American edition of Mrs Pargeter’s Pound of Flesh, a crime story set around a luxury spa’s weightloss programme. The very first words are British to their core:

Eleven stone three pounds.

Here in UK we pick from a smorgasbord of assorted units of measurement, both imperial and metric. Road signs display distances in miles, not kilometres, and I can’t ever imagine stating my just-over-6ft height as 1.84m. Shops have to show product weights in grammes and kilogrammes, although pubs are still permitted to sell beer and cider in pints, not half-litre measures.

In the US, people use an imperial measure to measure their weight. Well, so do we, but with the added spice of adding stones to the obligatory pounds.

‘Rebecca, what on earth is a stone?’, I hear you ask. Well, a stone is simply the next step up from a pound.

Ounces ➡️ Pounds ➡️ Stones

There are sixteen ounces to a pound, and fourteen pounds to a stone.

My weight of 10st 10lb, then, is an easy sum: 10 x 14 + 10 = 150 pounds.

Eleven stone three pounds – the weight of the protagonist of Mrs Pargeter’s Pound of Flesh, in which the action takes place at a spa hotel during a weightloss programme – is, erm, okay, the numbers are a little less straightforward than my own, hang on, I can’t do this one in my head….

11 x 14 + 3 = 157 pounds.

There. Easy. 😵💫

While enjoying my cover-to-cover read of the highly-enjoyable Mrs Pargeter’s Pound of Flesh I had kept my eyes peeled for any, well, non-British English spellings and turns of phrase, and I was surprised, actually, to find none.

I have read plenty of books in translation, and think it’s absolutely lovely that the language in this US-edition of this very British book remains untouched. Bravo to the publishers!

I had read ‘Der Besuch der alten Dame’ (‘The Visit of the Old Lady’), by Swiss playwright Friedrich Dürrenmatt, for my German A-level exam, and to my German lit teacher’s exasperation – ‘read the original, Rebecca! – I had picked up a copy of Maurice Valency’s English adaptation of the ‘The Visit’ when I went to see the play performed at the National Theatre in 1990.

The work had been translated into English, although steps had very clearly been taken to preserve, or even enhance, the Swissness of the piece for an English-speaking audience. The protagonist I had first met in my reading of the German-language original, Alfred Ill, had become the rather more Teutonic-sounding Anton Schill in translation, and lines to be spoken by the character of the mayor – Bürgermeister in the original German – were indicated by the label Burgomaster rather than Mayor in the English edition.

The inside pages of Mrs Pargeter have had their Britishness entirely preserved. Now, we all know we mustn’t judge a book by its cover, but the dust jacket of this one has been tailored beautifully to its US market.

Of course, it stands to reason that the back cover blurbs had all been sourced from US publications:

News and Observer, Raleigh, North Carolina

The State, Columbia, South Carolina

Booklist

Kirkus Reviews

Publishers Weekly

Denver Post

…Strong local colour…🇬🇧 – sorry, …strong local color… 🇺🇸 shines through here, with references to dry humor 🇺🇸 rather than dry humour, and dryly noted cultural tidbits… 🇺🇸 instead of drily-noted cultural titbits…🇬🇧

And the longest blurb, courtesy of Booklist, is one of the most sweetly amusing pieces of US-English writing about the British I have ever encountered:

Brett…. suffuses his whodunits with withering portrayals of British stock characters usually caught in bloody awful situations over which they react like so many prize twits.

Over here you’d only come across an expression like ‘bloody awful’ in informal dialogue (such as: ‘How was your day, darling?’ ‘Bloody awful.’), and I’m nearly 100% certain that I haven’t come across the term ‘prize twit’ since the late 1980s, and probably then only in reference to a pupil in a 1950s boarding school in the kind of teen fiction I was reading at the time. These are gorgeous clichés whose appearance has really made me smile!

Mrs Pargeter’s Pound of Flesh is a terrific read, its eponymous protagonist enlisting the help of her late husband’s colourful connections to get to the bottom of a baffling crime.

The case, of course, is solved, with all loose ends tied up beautifully by the end of the novel. But Reader, a question remains: how did the US edition of this delightful crime caper make it from a Louisiana library to a campsite in West Sussex less than fifteen miles from where Simon Brett had first written it over thirty years ago?

Well, I don’t know. That really is a mystery.

🕵🏻♂️

Love,

Rebecca

You can learn more about Simon Brett and his work on his website, simonbrett.com, and from this super article in Sussex Life magazine.

Regular readers of ‘Dear Reader, I’m Lost' will know that I have an ongoing writing relationship with

of in the form of regular, light-hearted correspondence on Wednesdays. It’s his turn to reply to me next time.If you’ve enjoyed this post, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you.

And thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

I think there should be books of Rebecca "Discovery Mysteries" -- on the same shelf as Pargetter, Christie and Doyle. Vol. One: "Found Shopping Lists". Vol. Two: "Found Books". Vol. Three: "Found Maps". Vol. Four: "Found Teabags". I love the way your mind immediately begins a sort of forensic detection, examining and parsing out clues to build a back story. I don't know anyone else who does that and it is so entertaining!

American usage of Britishisms sometimes go wrong in an amusing way, like when an American asked me if she could address an audience as Ladies and Blokes. I suppose that's no worse than my usurping of "y'all"!

Admirable post, Rebecca, jollification personified, and an excellent mystery.