154. The liberation of constraint

The paradox of setting boundaries to maximise creative freedom.

In which Rebecca reports on going back to school and considers the unexpected liberation she is experiencing from writing with constraints.

Thank you

for inspiring both me and this post, and hurrah for Oulipo founders Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais, who in 1960 set crazy rules for going creatively bonkers with words.Dear Reader,

Keen to exercise my writing muscles in a new way – and, more importantly, to take up the opportunity to learn under the tutelage of one of my favourite writers on Substack,

– last weekend I headed to City Lit in London for an all-day course entitled Creative Writing Using Constraints.It had been Terry himself who had first introduced me to the concept of Oulipo in his compelling series Experiments in Style, in which he rewrites the same story every Sunday using a different constraint each time. With over sixty fascinating variations in his canon so far, this is a project with perpetual potential.

What is Oulipo?

My favourite description of the concept comes from writer Rhys Hughes, which I have taken from the introduction to his book Mathematical Ghost Stories – Five Jamesian Oulipo Fictions.

Oulipo (Ouvroir de Litterature Potentielle) is a perennial workshop of experimental fiction that was founded by Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais in 1960. Its members attempt to create original and unusual fiction using mathematical and logical constraints that are arbitrary but rigorously applied.

The justification for Oulipo is that a writer confronted with a blank page, in other words at full liberty to write anything he or she likes, will surely fall into familiar and therefore low-level patterns. But once that liberty is restricted in some ingenious way, the writer will be compelled to create something that is normally beyond their inclinations. They will be nudged or even forced to think in a more lateral direction, to strive tangentially, to be original.

For his own Oulipo experiment in Jamesian Fictions, in which he wrote sequels for five stories by M R James, Hughes’ chosen constraint was to write stories ‘…exactly the same length as the original in every way, meaning that it would have precisely the same number of paragraphs, the same number of sentences in each paragraph, the same number of words in every sentence, and all the various punctuation marks of the original text would be replicated and placed in exactly the same positions.’

In Saturday’s course Terry introduced his students to a series of fascinating writing constraints. Bivocalism – the practice of using only two vowels in a piece of writing – and univocalism – using a single vowel – are both challenging examples, as is the lipogram– the omission of a letter.

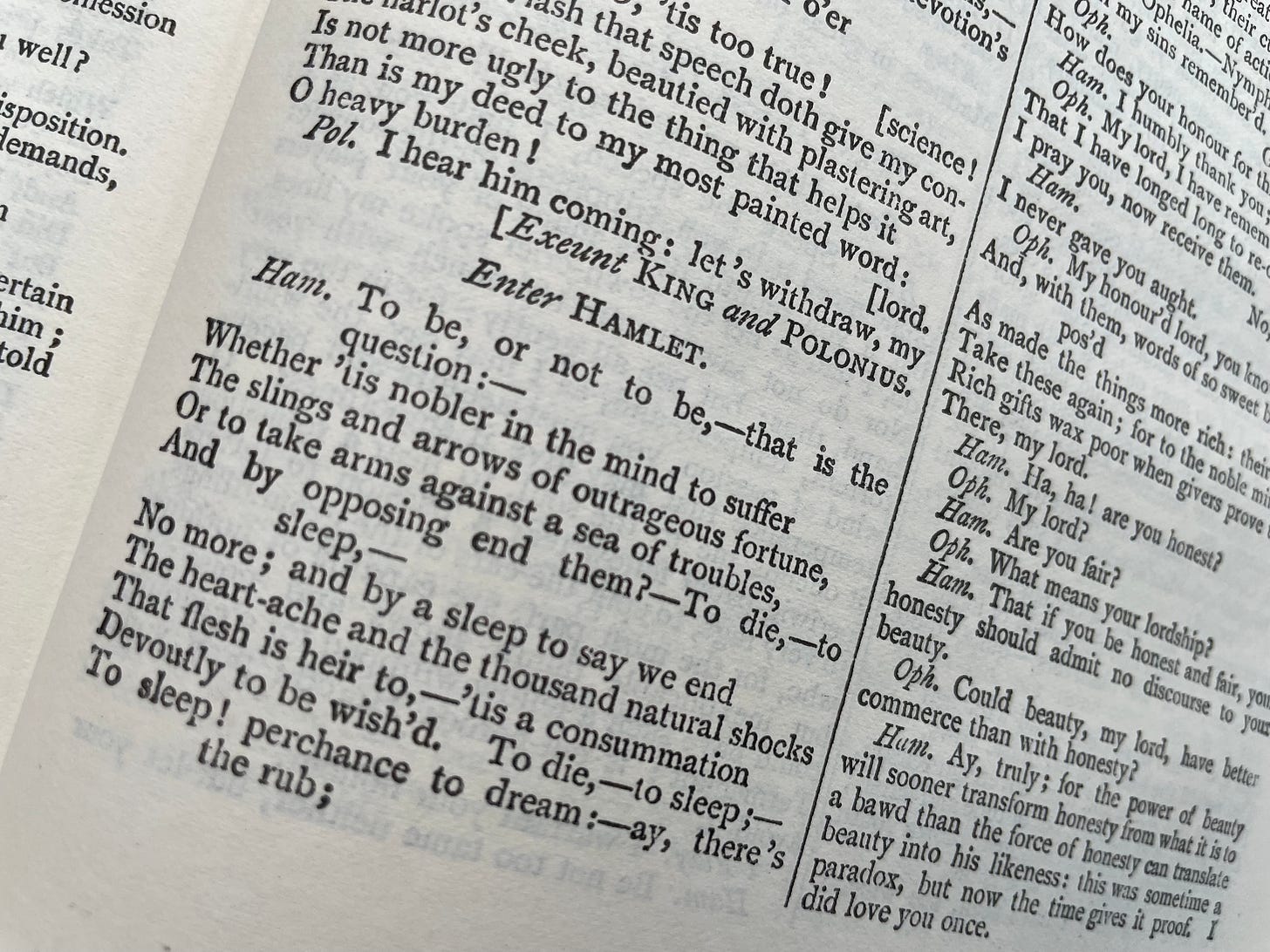

Shakespeare’s words ‘to be or not to be, that is the question,’ delivered by Hamlet in Act III Scene I of the eponymous play, change significantly when given the lipogram treatment in a, e or i.

The following three examples show how the lines have been rewritten to deliver a very similar message to the source text, yet do not include any words containing a, e or i respectively. For clarity, I’ve put the substituted words in italics:

Source text: To be or not to be: that is the question

Lipogram in a: To be or not to be: this is the question

Lipogram in i: To be or not to be: that’s the problem

Lipogram in e: Almost nothing, or nothing: but which?

Examples are an excerpt from Harry Mathews’ 35 Variations on a Theme from Shakespeare, provided by Terry Freedman.

Georges Perec took the treatment shown in the third example above – lipogram in e – to an impressive extreme in 1969 with his 300-page novel La Disparition (The Disappearance), in which he avoided using the letter e entirely. The subsequent English translation ‘A Void’ by Gilbert Adair is at least as impressive as Perec’s original text, it too containing not a single e.

I enjoyed the exercises which Terry set. One task had been to work individually on processing a source text using a technique in which we replaced certain words with their equivalents seven entries further on in the dictionary. Each of us had access to a different dictionary, and in our subsequent comparison of results and discussion about them we found their diversity remarkable.

Technique 1: N+7

N+7 is a simple constraint, requiring the replacement of each noun in a source text with the seventh noun listed after it in the dictionary.

I’m going to show you a source text which I am serving two very different ways using the N+7 technique and dictionaries out of my own bookcase.

Source text from Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Wuthering Heights

He little imagined how my heart warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyes withdraw so suspiciously under their brows as I rode up, and when his fingers sheltered themselves, with a jealous resolution, still further in his waistcoat as I announces my name. “Mr Heathcliff?” I said. A nod was the answer.

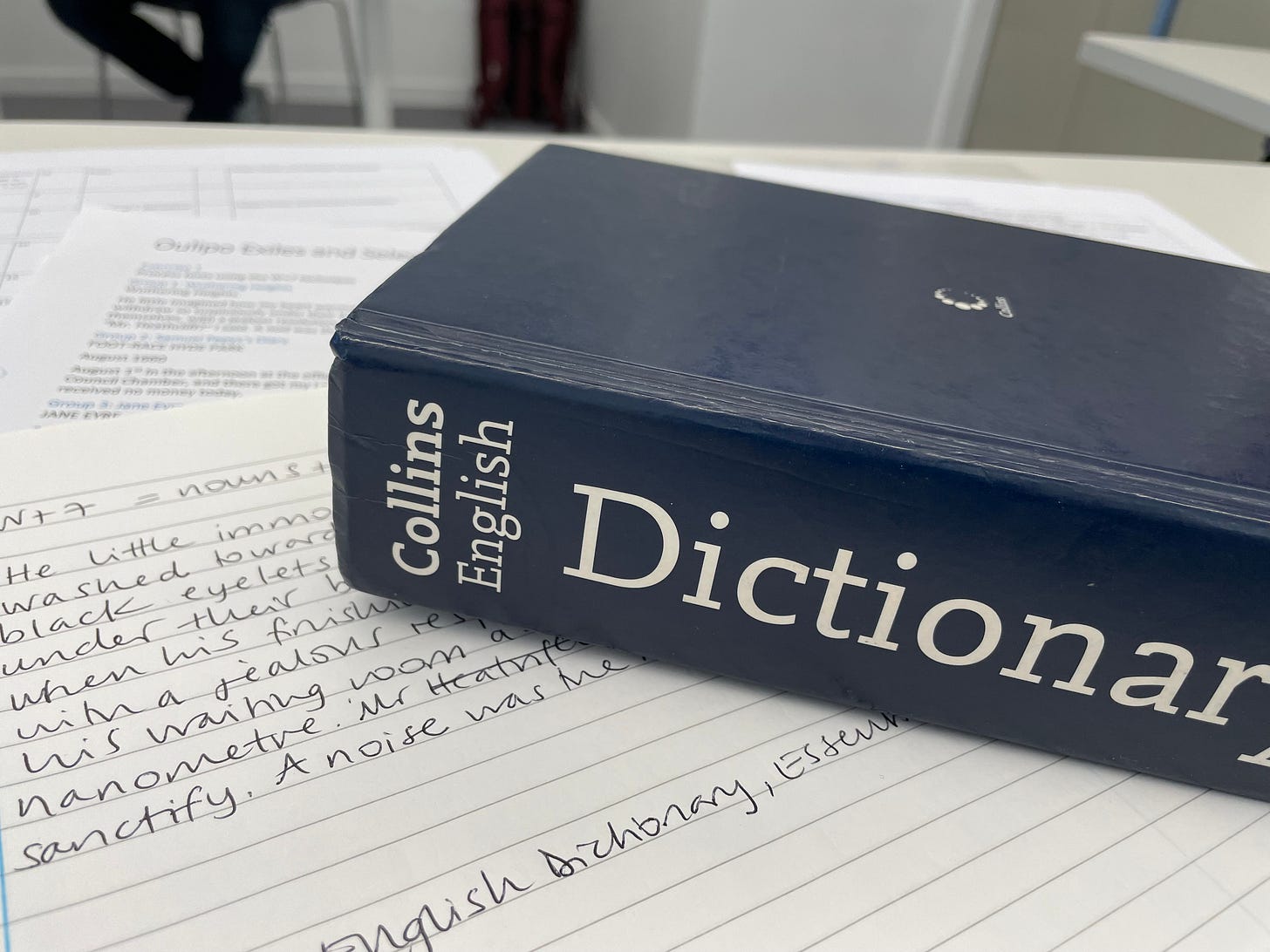

N+7 treatment using the Collins English Dictionary Essential Edition

Wuthering Heliports

He little imagined how my hearth warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyelets withdraw so suspiciously under their brunettes as I rode up, and when his finishing school sheltered themselves, with a jealous respirator, still further in his waiting room as I announces my nanometre. “Mr. Heathcliff?” I said. A noise was the Antarctic.

N+7 treatment using the Collins Reference English Dictionary

Wuthering Helix

He little imagined how my heaven warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyeholes withdraw so suspiciously under their brunettes as I rode up, and when his fipples sheltered themselves, with a jealous rest, still further in his wall as I announces my napkin. “Mr. Heathcliff?” I said. A nomad was the antecedent.

I learned a great deal from this N+7 constraint. As Rhys Hughes had explained in the introduction to Mathematical Ghost Stories, the intention of Oulipo is ‘to create original and unusual fiction using mathematical and logical constraints that are arbitrary by rigorously applied.’

Course tutor Terry reminded us that although we were using constraints in our writing, as writers we nevertheless have agency as to the extent to which we might decide to apply them, and indeed how we choose to utilise the results in our writing.

Technique 2: Anagram

The third reference book on my shelf is an anagram dictionary, and instead of using it for the N+7 technique I kept things relatively simple, seeking simply an anagram for each of the nouns.

That, at least, was my intention. I soon realised that there are no anagrams for several of the nouns in Brontë’s text, but while some in my own version have as a result remained the same as in the source, for two of them (in bold below) I have exercised a little more creative licence.

Anagram treatment using the Longman Anagram Dictionary by R J Edwards

Wuthering Eighths

He little imagined how my earth warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyes withdraw so suspiciously under their brows as I rode up, and when his fringes sheltered themselves, with a jealous win-or-lose, still further in his waistcoat as I announces my amen. “Mr. Heathcliff?” I said. A don was the ravens.

I know: ‘win-or-lose’ is not an anagram of ‘resolution’! There is no one-word anagram for ‘resolution’ – it’s the only word which the letters eilnoorsu can spell – but substituting the single-u with a double-u (w!) gives me the components to make ‘win-or-lose’. Not only is this more interesting, it is also fits rather nicely with the story of Brontë’s novel. 😁

The only word I can make out of ‘answer’ – the final word in the source extract – is, well, ‘answer’. Again granting myself some literary leeway, I substituted the w for a v. ‘Answer’ thus became ‘ansver’, and the fact that this is an anagram of ‘ravens’ gives, I feel, a rather Poe-etic1 spin to my Oulipo variation. 🐦⬛

What do I get out of all this?

Terry asked his students how using Oulipo techniques might help us in our writing, and Reader, I suspect you are wondering the same.

Here are some of the suggestions we talked about in class:

To break writer’s block

As a warm-up exercise

To stimulate new ideas

To take a break from a writing project

Just for fun

How Oulipo techniques might help me in my writing

Words are fun, and as the granddaughter of a lovely woman who had told me very many times ‘When I was your age I used to read the dictionary’ I have felt that way about them for a very long time.

Working with the N+7 technique has given me the unexpected treat of exposure to words I perhaps haven’t used for a while, some of which have sparked some ideas I might use in a writing project.

For instance, in my search for heights+7 I came across helicopter, heliograph, heliostat, heliotherapy, heliotrope, helium and helix.

And Reader, love both was and wasn’t lacking in my hunt for heart+7, in which I found heartache, heartbreak, heartburn, heartsease, heartthrob and heaven. ❤️Back to the intention of Oulipo being ‘a perennial workshop of experimental fiction’, Brontë’s source text and the application of the N+7 exercise together have given me a diverse selection of writing prompts:

Brontë’s phrase ‘jealous resolution’ would be an intriguing title for a story about a troubled relationship.

The rather more Oulipian ‘jealous restaurant’ might be the name of a gourmet eatery frequented by the food critic antagonist of a thriller – or, more likely, part of the headline for one of his food reviews.

‘Goodness gracious’, ‘flipping heck’ and ‘holy cow’ are all well-known expressions of surprise. Jennings and Darbishire2 had the more unusual ‘fossilised fishhooks’, but how about ‘wuthering heliports’ for an entirely novel expostulation? Reader, I rather like it!

My N+7 phrase ‘when his fipples sheltered themselves’ takes my imagination for a walk alongside a babbling brook in the shelter of the fipples. Now, that’s a nice title for a bucolic ballad.

In one of my N+7 exercises ‘a nod was the answer’ became ‘a nomad was the antecedent’. The first is not terribly interesting and the second is bananas, but if I combine elements of the source text and my post-processing Oulipo text I end up with ‘A nomad was the answer’.

And suddenly, with the addition of a comma, I have a line of dialogue – shown below in italics – from a scene in a Marrakech souk featuring an enigmatic stranger:

‘Who’s that?’ I asked Kabir as he transferred tangerines from an overfilled box onto his trestle table.

The seller raised his head only briefly, and went back to piling up the fruit.

‘A nomad’, was the answer.

Technique 3: predictive text

Okay, so I came up with this crazy idea for myself, but replacing words with apparently unrelated ones got me thinking about the vagaries of the technology around the predictive text feature available in computer software and apps.

What is predictive text?

Predictive text is an input technology that facilitates typing on a device by suggesting words the user may wish to insert in a text field. Predictions are based on the context of other words in the message and the first letters typed.How predictive text uses machine learning

Predictive text uses machine learning to guess a writer’s next word based on their writing style. As the user types, the machine learning algorithm notes commonly used words and creates a personalized dictionary.The algorithm makes repeated observations and becomes attuned to the user’s style. It also notes of the last few words the user wrote and narrows its suggestion based on those words. This is known as context-sensitive text prediction.

Well, my Mac computer’s Mail and Message apps often try to get ahead of themselves and offer me – halfway through many of the words that I type – all kinds of preposterous alternatives to what my fingers are attempting to get onto the screen.

Here’s what Mail came up with when I copy-typed the Brontë source text into a draft e-mail:

Wither Heights

He little imagine how my heart warmed towards him when I bet his black eyes with so suspicious under they brows as I rode up, and when his fingers shelter themselves, with a jealous resolution, still further in his waist as I announced my name. “Mr Heath?” I saw. A nod was the answer.

Reader, this was rather fun: in fact, I bet my black eyes that I could play some more with this constraint! And hey, Wither Heights is an even more interesting address than its Wuthering next-door neighbour…

I had already learned a great deal from

’s Experiments in Style project on , but taking his course at City Lit has provided a toolkit for using constraints to broaden my own writing horizons. I have even more to discover about the creative potential of using Oulipo techniques to invigorate my writing practice, and Reader, I am looking forward to playing with as many of these as I can find in order to indulge myself even further in the sheer joy of words.Love,

Rebecca

If you’ve enjoyed this post, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

Excuse the pun. It was irresistible.

The Raven by Edgar Allen Poe.

Writer Anthony Buckeridge’s Jennings books were highlights of my childhood reading experience.

"Who’s that?’ I asked Kabir as he transferred tangerines from an overfilled box onto his trestle table.

The seller raised his head only briefly, and went back to piling up the fruit.

‘A nomad’, was the answer"

This is a great example of how the oulipo can create "potential literature" .

Very interesting write-up, and it's nice how you've adapted and invented techniques to make them your own.

Queneau defined oulipians as rats who create the labyrinth from which they then try to escape 😁

Wow! This is a little—ok much—over my noggin.

I like labyrinths, (referring to Terry’s definition of “oulipians”, however, with walls low enough that I may see over so as to not get so lost. Not saying I don’t like a good adventure, but, as someone who maxed out with a GED, this country gal prefers a simple, more direct writing tone as in conversational storytelling. (If that’s even a thing?)

I wish I had the cranial capacity at almost 72 years to remember new writing skills, but with my over indulgence on my iPhone and laptop, not to mention many years of having imbibed too much alcohol, some of my synapses are not firing on all cylinders. Although I’m always learning, I don’t think I could stuff one more class into my ‘dayness’.

I do love that you are always experimenting with words, phrases and writing. ❤️🤗