145. Old gold: When bluebells seemed like fairy gifts

A (quiet) fanfare for the silent eloquence of a springtime treasure.

Dear Reader,

I had the pleasure last week of a walk through a local bluebell wood with my mum. Arlington Bluebell Walk opens daily in April and May, and since it opened in 1972 the event has raised over a million pounds for local charities, which take it in turns to provide refreshments to visitors. Catering on the day of our visit was supplied by St Wilfrid’s Hospice, and we can vouch for the excellent coffee, tiffin and gluten-free lemon drizzle cake which fuelled our muscles for our walk.

Cicely Mary Barker, writer and illustrator of the beautiful Flower Fairies poems, calls the Bluebell Fairy ‘the peerless Woodland King’, and I’d published a version of this Old gold post on the day of Charles III’s coronation in May 2023.

My hundred thousand bells of blue,

The splendour of the Spring,

They carpet all the woods anew

With royalty of sapphire hue;

The Primrose is the Queen, ’tis true.

But surely I am King!

Ah yes,

The peerless Woodland King!

If you’re reading this post for the first time: welcome, and I hope you enjoy it. If you’ve read it before: thank you so much for sticking around to read it again!

With love,

Rebecca

When bluebells seemed like fairy gifts: a (quiet) fanfare for the silent eloquence of a springtime treasure.

Spring provides us with plenty of goodies to fuel the language of poetry. There is birdsong and sunshine, and the new season’s sights, sounds and scents abound: spring is a delight.

Early last month I spotted the first shy wood anemone on a woodland walk. I’m always keen to observe the annual variation in the fickle timetable of the flowering of anemones and bluebells: in the early warmth of last year’s spring they were out together in a burst of white and blue in one glorious eyeful, but this year, when spring has been taking its sweet time to get started, the anemones enjoyed an almost independent season. For a few weeks they had owned the woods and verges.

Wood anemones are unassuming flowers with – like me – a strict bedtime. They don’t open their petals until the light of day is enough to wake them, and as the evening light fades, so does their energy. At night they close their flowers: each multi-petalled bloom folding into a circle like the moon above them.

Bluebell foliage was already in evidence of sorts in February: the glossy fresh green spears pushing their way up through a rustling brown carpet of beech leaves, but I didn’t see my first bluebell in flower until mid-April. By then the anemones were already carpeting the woodland floor with their stars, the bluebells playing catch-up to their head start.

In my south-east corner of England, it is in April and May that we welcome a glorious showcase of British native bluebells, Hyacinthoides non-scripta. Blue is often considered to be a cold colour, but bluebells are a warm blue, almost violet, and the vast swathes of this beautiful flower carpeting forest floors at this time of year are absolutely breathtaking.

The scent of a bluebell is not unlike that of its close and larger relation, the hyacinth. Yet the all-consuming scent around me as I walk through a softly sunlit bluebell wood on a warm day is almost overwhelming: thousands of flowers share their scent with passers-by in a profusion of perfume.

Ah, that perfume: if only it could be gathered up and bottled. Well, London perfumier and Royal Warrant holder Penhaligon’s, established in 1870, has been making its fragrance ‘Bluebell’ since 1978. It describes the scent as: “A pure and unadulterated distillation of the scent of bluebell woods”, and tells prospective purchasers that “If you go down to the woods today... a fragrant carpet of bluebells awaits. Breathe deep. Citrus, hyacinth, clove. An eau de toilette reminiscent of childhood escapades in the fresh, dewy spring.”

For me there’s something rather more special – not to mention much less expensive – in seeking out the scent of real bluebells in season in April and May. Just like I don’t enjoy eating asparagus as much outside its season of St George’s Day to Midsummer’s Day, I’m not sure I need to drink in the scent of bluebells when the flowers themselves are not in evidence.

There’s another kid on the block of blue spring flowers at this time of year, though, and the Spanish bluebell, Hyacinthoides hispanica, is a pretty plant, with unscented flowers arranged all around its erect stem.

Yet despite the springtime British splendour of a carpet of bluebells, the posture of a single native specimen is lowly and unassuming. Its head is bowed, bells hanging down from its arched stem.

This unexpectedly humble aspect of a bloom which in its Maytime multitude is easy to miss endears it to me as much as it did to writers of the past.

Anne Brontë included these words in her poem ‘The Bluebell’:

There is a silent eloquence

In every wild bluebell

That fills my softened heart with bliss

That words could never tell.

…

But when I looked upon the bank

My wandering glances fell

Upon a little trembling flower,

A single sweet bluebell.

…

O, that lone flower recalled to me

My happy childhood's hours

When bluebells seemed like fairy gifts

A prize among the flowers

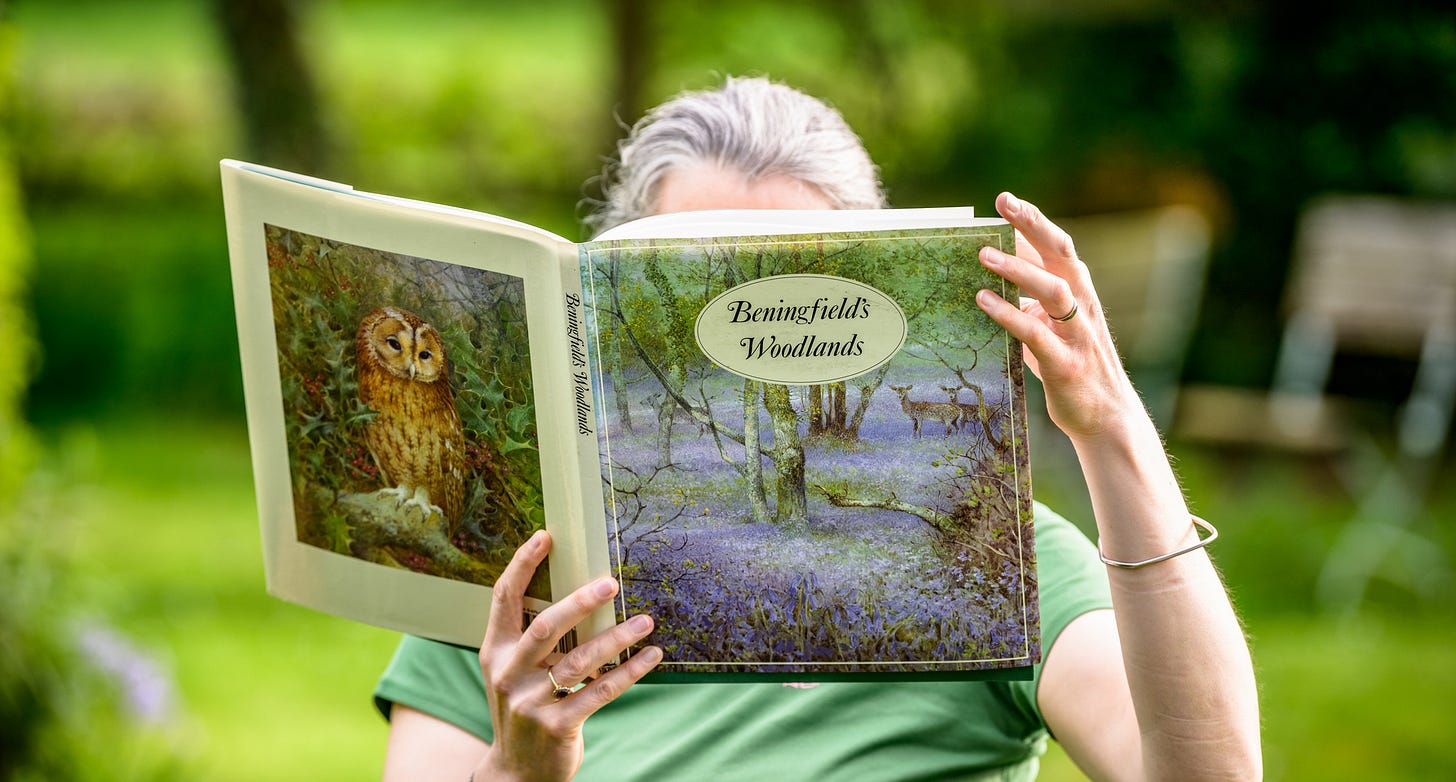

In his stunning book ‘Beningfield’s Woodlands’ nature artist and writer Gordon Beningfield explains why bluebells are so special:

Bluebell woods are one of the wonders of the world, and nowhere are they more spectacular than in Britain. The carpets of violet-blue flowers shimmering under the dappled spring sunlight in a hazel coppice of oak wood are an unforgettable sight.

The damp climate of Britain clearly suits bluebells… Over most of southern England, however, they seem to need the moist atmosphere of woodlands, though they will survive in hedges and under bracken where the trees that have sheltered them from time immemorial have been destroyed.

Bluebells spread very slowly – the heavy black seeds that drop out of their seedcases are unlikely to travel very far – and bluebell woods are mostly ancient in origin. This means that even if modern tree plantations were suitable for bluebells (which they are not), it would take a very long time – centuries perhaps – for new woodland to develop the swathes of flowers that are a springtime national treasure. Our ancient bluebell woods are irreplaceable, and, like woods in general, have fallen victim to the government-encouraged greed of farmer and foresters.

Taken from ‘Beningfield’s Woodlands’ by Gordon Beningfield, published by Viking, 1993

According to the Wildlife Trusts, the UK’s woodlands are home to almost half of the world’s population of Hyacinthoides non-scripta, but it seems that these bluebells – the ones which in their glorious violet-blue carpets bring such gorgeous delight to my walks at the moment – are under threat from their more robust and upright continental cousins.

In the case of Hyacinthoides hispanica – rather like the grey squirrels threatening our native species of reds: a topic that I enjoyed exploring in my post ‘Going nuts: a nature story’ – the Victorians seem to have a lot to answer for:

The Spanish bluebell was introduced into the UK by the Victorians as a garden plant, but escaped into the wild – it was first noted as growing ‘over the garden wall’ in 1909. It is likely that this escape occurred from both the carefree disposal of bulbs and pollination. Today, the Spanish bluebell can be found alongside our native bluebell in woodlands and along woodland edges, as well as on roadsides and in gardens.

This member of the bluebell family is not quite so blue: it is paler perhaps, with its violet tones not as saturated as those of its native cousin. Standing tall in spring flowerbeds and borders Spanish bluebells make a confident impression: their bell-shaped flowers opening wider than those of their native cousins, petals outstretched. In a woodland setting these blooms would be obvious strangers to their bowed-headed cousins which have naturalised in English woodlands over generations, but as flowers to enjoy in the garden they are beautiful, and I’m pleased to have them in my own back yard.

Spending time walking through a native bluebell wood with one – or more – of my favourite people is one of my highlights of a British spring. And if there’s cake to be had to fuel my way, well, so much the better.

Love,

Rebecca

If you’ve enjoyed this post, do please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

The bluebell is beautiful but the wood anemone is perfection...

What a gorgeous and interesting post Rebecca! I fell in love with your bluebell wooded areas when some of my instagram friends were posting them in their feeds several years ago. They truly have a fairy like quality and must be absolutely jaw dropping to see them in their glory in real life! Your close ups were so beautiful!

I couple of years ago I planted a few bluebells (not sure what kind they are) in my front gardens. When they arrived the first year, I couldn't believe how tiny the little bells were. Just today I noticed that mine were budding once again. I'll be so excited to see them once more this year. Wish I could groupings like yours in full abundance!

Thanks for introducing me to Benningfield's Woodlands book---looks and sounds like a beautiful book.

Thanks for sharing Rebecca---how wonderful you could take this magical walk with your mom! xx