Dear Reader,

Asparagus does not share a happy plate with the festive turkey: like indulging in imported strawberries at Christmas, eating those juicy green spears out of season feels – and tastes – meh.

Yet I always keep a keen eye on the calendar for the arrival of St George’s Day in April, in giddy anticipation that our local asparagus farm will be open for business on that first day of the season.

Alas, here’s what their website told me this morning – four days after St George’s Day:

STOP PRESS!

Asparagus News

🌱

Our beds are prepared and all set to go, but the chilly winds and cold nights are holding the crop back. We are poised and ready to go, but desperately need some warm weather. Thanks for your patience. Please watch this space for updates.

An early memory in my long asparagus-eating career is of soggy, slimy, stringy stuff which had been cooked to death.

These days I enjoy the real stuff: delicious spears getting on for eight inches long which are tender, thick, and a beautiful shade of purple-tinged green.

Even its name is lovely.

The etymology of asparagus is interesting – many people think that it was called sparrow grass, but the upper class thought it a vulgar term and subtly changed its name to asparagus to make it sound more posh. This is not quite true: it actually began life as asparagus coming from Mediæval Latin, then it was shortened to sparage in Late Old English and then further modified to asperages in Middle English. It was anglicised to sperach or sperage in the 16th century, but strangely it was officially spelled as asparagus to be in line with Latin. The word asparagus became associated with “stiffness and pedantry”, and the folk-etymologised sparrow grass arose in reaction to these Latin throwbacks.

Lasting from April only until midsummer, the brief asparagus season sees my yearning for that first juicy spear grow into a compulsion to gorge on a ceaseless supply before harvesting stops in June.

As an ingredient in other dishes I have been disappointed far too many times by the unpleasant colour and texture of what is supposed to pass for asparagus but doesn’t: overcooked floppy stems tipped out of a tin and into a tangled mess in a soggy quiche. Yet fresh spears in season are a treat fit for a king when served as simply as possible: lightly steamed and eaten with one’s fingers.

Indeed, how you eat asparagus reveals your social class, according to the head researcher from The Crown reported in an article in The Daily Telegraph published on Saturday December 23, 2023.

Annie Sulzberger has revealed that while working on an episode of the Netflix series, she was informed by an etiquette adviser on set that “posh people don’t eat asparagus with knives and forks”.

“In one scene, Dominic West was eating asparagus at Highgrove. Our amazing etiquette adviser, David Rankin Hunt, stopped him and said ‘Posh people don’t eat asparagus with knives and forks – they use their fingers’. So we reshot it with Dom picking up the asparagus with his fingers.”

Debrett’s, the guide to etiquette and table manners, advises that in general one should avoid using one’s fingers “though it’s fine to pick up asparagus (without a sauce)”.

It goes on to state: “Asparagus is always eaten with the left hand and never with a knife and fork,” adding that stalks should be eaten down “to about an inch and a half from the end.”

Taken from The Daily Telegraph, Saturday December 23, 2023.

Despite the asparagus season beginning on Shakespeare’s birthday – St George’s Day itself, April 23 – I can find no reference to asparagus in any of his plays.

He is likely to have come across it, though. Shakespeare was born in 1564 and lived until 1616, and this Wikipedia entry which tells me that ‘asparagus appears to have been little noticed in England until 1538’ implies that the delicacy has been around since the first half of the sixteenth century.

We do know that Samuel Pepys knew his greens, as this entry from his diary shows:

Saturday 20 April 1667

So home, and having brought home with me from Fenchurch Street a hundred of sparrowgrass, cost 18d. We had them and a little bit of salmon, which my wife had a mind to, cost 3s. So to supper, and my pain being somewhat better in my throat, we to bed.

I applaud Mr & Mrs Pepys’ supper choice, for asparagus and salmon make a delicious combination, and I am interested that Pepys had paid exactly twice as much for his ‘little bit of salmon’ as he had for the asparagus. Today’s pound sterling equivalent of Pepys’ 18d-worth of spears is around £15.00, whereas the 3s he’d paid for the salmon in 1667 now equates to £30.00.

Fifteen quid for asparagus, thirty for salmon? Ouch! 🤔

Now, I don’t know how many grammes Pepys’ ‘a hundred of sparrowgrass’ equates to, but I have seen a kilogramme of asparagus for sale this week for £10.50. The price typically falls as the season’s harvest becomes more plentiful, and I hope that will also be the case this year, otherwise I’ll be broke within a week.

Asparagus features in the work of a number of other writers. In his 1913 novel ‘Swann’s Way’ Marcel Proust waxes lyrical about it, even using beautiful language to describe the unfortunate effect that its consumption is known to have on the pungency of the diner’s post-prandial pee:

Asparagus, tinged with ultramarine and rosy pink which ran from their heads, finely stippled in mauve and azure, through a series of imperceptible changes to their white feet, still stained a little by the soil of their garden-bed: a rainbow-loveliness that was not of this world. I felt that these celestial hues indicated the presence of exquisite creatures who had been pleased to assume vegetable form, who, through the disguise which covered their firm and edible flesh, allowed me to discern in this radiance of earliest dawn, these hinted rainbows, these blue evening shades, that precious quality which I should recognise again when, all night long after a dinner at which I had partaken of them, they played (lyrical and coarse in their jesting as the fairies in Shakespeare’s Dream) at transforming my humble chamberpot into a bower of aromatic perfume.

Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way

I’d asked Mum about my parents’ experience of growing asparagus, having remembered their tremendous preoccupation with the preparation of a particular area of the vegetable garden when I was small, even down to the announcement they made:

‘This will be the asparagus bed!’

Mum described the planting project. ‘An asparagus crown looks like an octopus, and it takes a long time to grow. To plant it, you make a mound and drape the octopus over it.’

She paused. ‘It’s years before you can harvest it. And even when we did, we had very little asparagus.’

Mum told me that there would only be a few spears every year, ‘usually when Daddy was away1, so I had it all, and it was usually around my birthday.’2

The asparagus bed remained a relatively unpopulated fixture in the vegetable patch for years, although growing the stuff had long been judged ‘not worth it’, as we live in an area where asparagus is grown on a commercial scale.

Yet it’s not as if my parents hadn’t done their homework.

Lawrence D. Hills had had plenty to say about asparagus in the book to which my parents have always referred both during our years of self-sufficiency and subsequently – Grow Your Own Fruit & Vegetables, published in 1976 – and I can see from a note in the margin that my parents’ foray into growing the stuff had first occurred ten years later. You can find Hills’ actual instructions for growing asparagus in this footnote3, but here’s a summary of how I imagine any future efforts of my own4 in this regard might look:

Year 0 – autumn

Prepare soil.

Yay! Can’t wait for April!

Year 1 – February

Scatter over fish meal and wood ash, dig it in.

Yay! We’re planting asparagus next month!

Year 1 – March

Plant asparagus crowns.

Yay! We’re growing asparagus!

Year 1 – April to June

What do you mean, there isn’t any?

Year 1 – November

Cut down ferny foliage

This would look pretty in a vase. Can’t eat it, though.

Year 2 – March

Scatter over fish meal and wood ash, dig it in.

Blimey, this is hard work, and it stinks. Roll on April.

Year 2 – April to June

Did we miss the asparagus?

Year 2 – November

Cut down ferny foliage. Cover plot with manure.

All hope is lost. Leaves vase in cupboard.

Year 3 – March

Scatter over fish meal and wood ash, dig it in.

Anybody hungry?

Year 3 – April to June

When the shoots are five to six inches above ground, cut them four inches below the surface.

Sits down in shock. Devours the single spear in evidence.

Year 3 – Five weeks later

Stop cutting.

Hang on, was that it?

Year 3 – November

Cut down ferny foliage.

Swears at shears. Mumbles about how this stuff gets haircuts more frequently than self. Throws vase away.

Year 4 – April to June

When the shoots are five to six inches above ground, cut them four inches below the surface.

Faints. Comes round. Demands Hollandaise sauce.

Year 4 – Eight weeks later, or by 21st June, whichever comes first

Stop cutting.

Has a lie-down, having eaten too much asparagus.

Year 4 – November

Cut down ferny foliage.

Throws foliage onto compost heap. Sighs. Adds vase to Christmas list.

At my parents’ house a couple of days ago I came across their asparagus steamer. ‘Aha!’ I said. ‘The season is upon us!’

‘You know that was a joke present, don’t you?’ asked Mum.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, we’d planted the asparagus, so for Daddy’s next birthday I bought him the steamer.’

‘Ha! Bet you only christened it years later!’

‘Well, we never actually produced enough asparagus for a meal.’ Mum sighed. ‘And then we gave up.’

But Reader, we didn’t give up eating it.

Remember that quote from British Food: A History?

The word asparagus had become associated with “stiffness and pedantry”, and I’m pleased about this, because that gives me hope for those people out there who inexplicably don’t enjoy eating the stuff ‘because of its unpleasant texture’.

Well, I’m a pedant about how I cook my asparagus, and it needs to be stiff. I can’t imagine Dominic West – or even the king himself – picking up a floppy length of the stuff to eat with his fingers. That, dear Reader, is a soggy string unworthy of the name ‘spear’ and one which is absolutely impossible to eat with your fingers.

Cooked properly my way the texture of asparagus is far from unpleasant: steamed for just 3-4 minutes, the spears remain tightly firm with just a slight bite.

We steamed some asparagus in the van while we were camping last June, and ate it with our fingers, dipping its tips untidily into our stew. And a few weeks ago – when I couldn’t resist buying a few spears of early-crop British asparagus from our online grocery delivery service – we served it with salmon pestotto5, and again we ate it with our fingers.

So, what’s it like? I can’t tell you precisely, apart from to say that it tastes like asparagus. Munching on the cut ends raw, though, as is my bad habit when preparing spears for steaming, takes me right back to my childhood when we used to pod the peas harvested from my parents’ garden, and for every three peas that went into the bowl at least one two three more would land in my mouth. Uncooked asparagus has that same flavour, whereas cooked asparagus takes like, well, asparagus.

Helpful? No? Sorry. Well, you’ll have to try it. You’ll soon see what I mean.

Reader, I wouldn’t grow it, though. And I’m in good company: Lawrence D. Hills, writer of that book to which my parents had referred way back in 1986 when attempting to establish their own crop, doesn’t seem to recommend doing that either.

Here’s a snap of the last part of Hills’ chapter on asparagus. I can only imagine what the words concealed by the firmly-stuck label might say.

An asparagus bed is a[…….]

[…….] for those who like it. It […….]

On the next page he concludes the chapter with this:

[com]pare with so many other vegetables needing less room and making less work.

So, even Hills had found the stuff rather too much trouble to grow. Perhaps he might have appreciated having an asparagus farm on his doorstep during this delicious time of year between St George’s Day and midsummer.

Now, if the weather would only warm up our local commercial grower might at last begin the harvest.

Love,

Rebecca

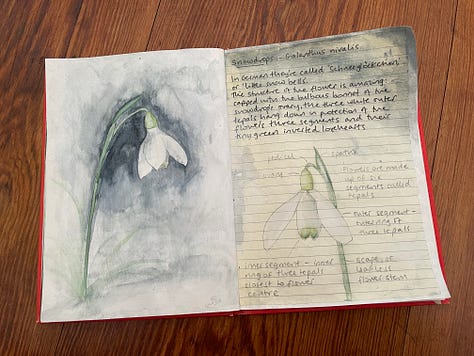

Artist’s notes

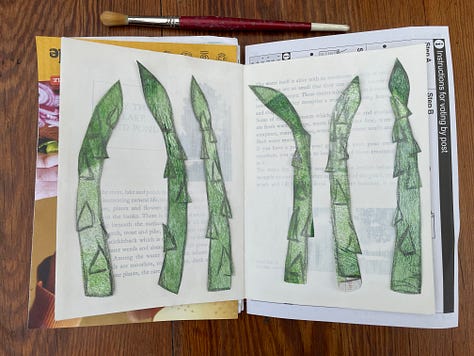

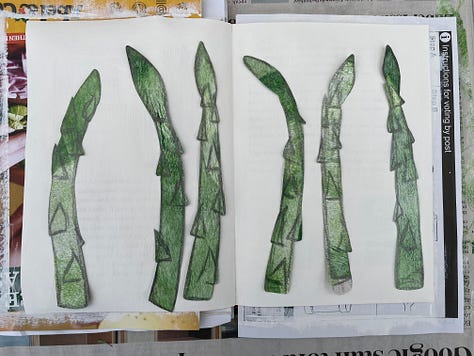

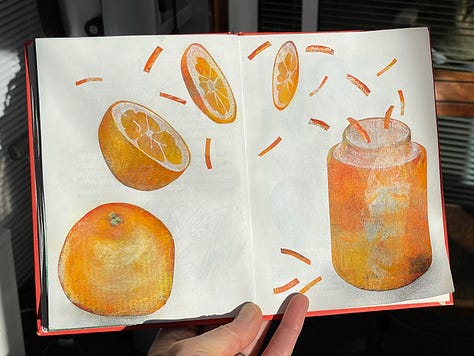

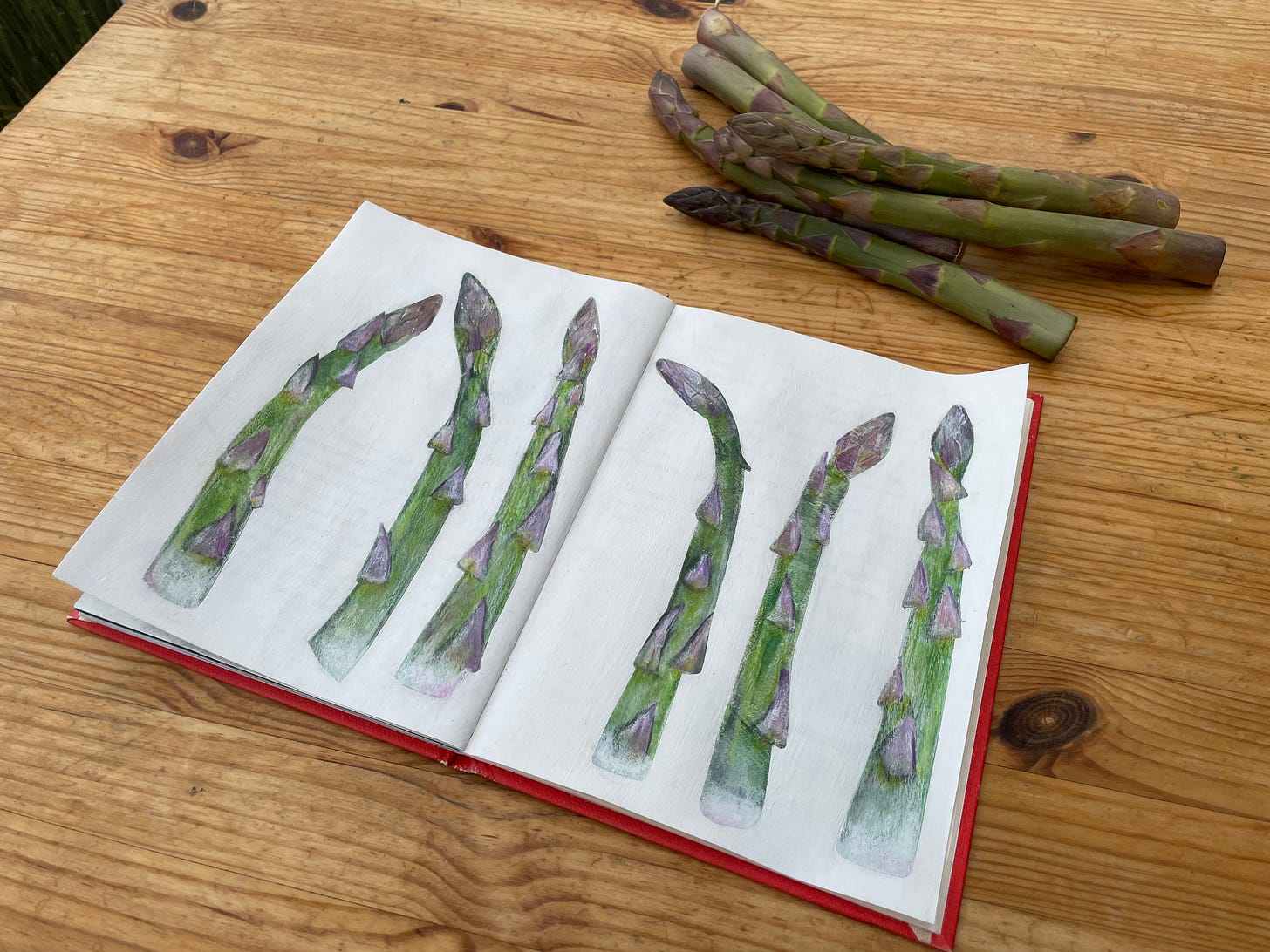

One of my favourite art techniques involves the random rolleration6 of thick acrylic paint onto newspaper to create elements for collage. You might recognise the two projects pictured below from my Art & Treasures 🖼️ posts last year.

Here are the stages for my mixed media asparagus:

Random rolleration of acrylic paint onto newspaper. I used sap green, white, Payne’s grey and magenta, and let the roller do the work.

I chose interesting parts of the painted paper and roughly drew some asparagus spears using a water-soluble 4B graphite pencil, and cut them out.

Working out my composition. While I was laying out my paper asparagus into my vintage book art journal I found the background of my spread needed some attention, and it was at this point that I decided to obscure the book text to a greater degree with an additional layer of both white paint and gesso.

I trimmed and refined the pointy edges of my collage elements before sticking them down using matte gel medium.

I added detail using water-soluble wax crayons, white gouache, watercolour paint and coloured pencil. What I love about working in mixed media best of all is my ‘more is more’ mantra!

We ate all six real-life spears for supper last night, and three of these are pictured before they hit the steamer. Yum!

📚 Reading 📚

📚

of wrote a tantalising post last week to celebrate Earth Day, in which she shared three ways to keep a notebook like a naturalist. I love this kind of thing, and one day hope to begin my own nature-based sketchbooking habit.📚

encouraged her readers in this post on to ‘carry a sketchbook everywhere’. ✔️📚 I’ll say it: I lack confidence in my art. It feels like a big deal if I bypass my pencil and hit my page with ink or paint straight off, or to deliberately put my eraser where I can’t find it so that I have to commit to my lines. In this thought-provoking post,

of addresses the debate:📚 Regular readers of ‘Dear Reader, I’m Lost' will be no strangers to my ongoing light-hearted correspondence with fellow Brit

of . It’s my turn to reply to him next Wednesday, and I can’t wait!If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, the latest in a monthly series exploring some of my memories in words and pictures, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you! You’ll find all the posts in this ‘Art & Treasures’ series here.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

Dad: longhaul pilot; accidental asparagus-dodger. ✈️

Late April.

Asparagus… is planted as a year-old crown. Allow eighteen inches between them in single rows four feet apart when deciding how many to order for March delivery. For early cutting they need soil sun-warmed; choose a sunny and sheltered place and dig it several times to remove all perennial weed roots. Then dig again to turn under a good barrowload of manure to every three square yards and leave the surface rough through the winter.

Next February scatter 4oz of fish meal and 8oz of wood ashes to the square yard, dig again to get rid of still-surviving weed roots and take out trenches six inches deep and eight inches wide for the rows. In March set out the octopus-like plants with eighteen inches between the middles and the roots spread out. Put back three inches of soil worked and firmed between the roots (with fingers, not feet) and leave the trench as a depression to hold rain or watering if summer is dry.

…in the first season… the plants grow only ferny foliage. Cut this down in November.

When March comes again repeat the fish meal and wood ashes, for asparagus is a seashore plant and enjoys the salt, and dig a shallow ‘U’ four inches deep and two feet wide between he rows, to make the roots go deep in the middles instead of growing awkwardly shallow. Heap the soil by the side of and not over the plants to make another water-holding dip for a summer of fern-growing, raking it back to the middles at the November cut-down-and-clean. This time cover the plants with a two inches thick, one foot wide strip of good manure.

After fish meal again in the following March, heap the soil from between the rows four inches high in ridges over the plants. When the shoots are five to six inches above ground, cut them four inches below the surface, scraping away and replacing the ridge soil. Leave the fern to grow after five weeks’ cutting this first season, and after eight weeks’ cutting in others, always finishing before 21st June to allow next year’s crop to grow.

Not gonna happen.

Risotto + pesto = pestotto. Probably only a thing in our house, to be honest.

Not an official art ‘thing’. I made this phrase up.

I attended college in western Massachusetts. In the fields around the college and along the railroad tracks wild asparagus grew. We would take buckets out hunting the wild asparagus, bring our bounty back to the dorm where we would cook it all and drizzle it with melted butter...heavenly! Thanks for your writing which ,so often ,evokes great memories!

Do you have fiddleheads over there? Similar season, similar risks of overcooking. I find it can taste like asparagus, but as an unfurled fern (say that 5x fast), it grows all over the place. And also like asparagus, if it’s soggy, it better be in a puréed soup!