Dear Reader,

Given my inability to find my way instinctively – or otherwise – through the landscape I’ve often wished that I could navigate with the intuition of an animal; to have been pre-programmed with an innate ability for natural navigation.

How are our animal friends tuned in to finding their way around, and is such an ability simply part of their make-up?

I was intrigued by an article in an edition of Sailplane & Gliding magazine from last summer entitled: ‘A Shared Way of Navigation: Study suggests that honeybees follow linear landmarks to find their way home, just like the first pilots.’1

A study has shown that ‘honeybees retain a memory of the dominant linear landscape elements in their home area like channels, roads and boundaries.

When honeybees find themselves in unfamiliar territory, they fly in exploratory loops in different directions and over different distances, centered on the release spot. With radar, the researchers tracked the exact exploratory flight patterns of each bee.

The test area contained a pair of parallel irrigation channels. The bees’ search pattern was shown not to be random, and advanced statistical analysis showed that they spent a disproportionate amount of time flying alongside the irrigation channels.

Analyses showed that this continued to guide the exploratory flights even when the bees were more than 30 metres away, the maximum distance from which honeybees are able to see such landscape elements. This implies that the bees kept them in their memory for prolonged periods.

Taken from Sailplane & Gliding, Vol. 74 No. 3 (June/July 2023), pages 28 to 29.

The authors of the study offered this conclusion:

Flying animals identify… extended ground structures in a map-like aerial view making them highly attractive as guiding structures. It is thus not surprising that [they] use linear landmarks for navigation.

But it’s not just flying animals which use linear landmarks for navigation; I do, too. As a disorient I find it hard to identify the kind of non-tangibles that those with a better sense of direction, such as my husband, seem to use without even thinking: the tracking of the sun across the sky, knowing that ‘that way’s north, obviously’, and ‘because my shadow’s that long and on this side of me, it’s clearly four o’clock/autumn/that way [delete as appropriate]. Given a time constraint (such as ‘please get home alive and unlost by lunchtime’) and the choice between a meandering path through a local woodland or a straight footpath along a main road, well, I’ll choose the latter in a heartbeat.

I can’t identify signals or unscramble cryptic signs. I’d make a rubbish spy; instead of lying in wait to observe my quarry I’d blithely follow their every step for fear of losing not just them, but also my way.

We had found ourselves with a day to spare after a shoot in Bedfordshire, and headed to Bletchley Park.

Once the top-secret home of the World War Two Codebreakers, Bletchley Park is now a vibrant heritage attraction, open daily.

Immersive films, interactive displays, museum collections and faithfully recreated WW2 rooms will guide you on a journey to discover the past at Bletchley Park. Exhibitions, set within beautifully restored historic buildings, tell the story of this once top-secret operation. Find out more about the brilliant minds and complex machines that made this vital work possible, and discover the global impact Bletchley Park had on the outcome of WW2.

Taken from the Bletchley Park website.

Every part of the site was absorbing, and although we didn’t avail ourselves of the audio guides we found that the interpretation boards steered us happily on our self-guided journey2 through the visitors’ centre, the mansion and the huts in which innumerable secret intelligence tasks had been undertaken by a vast cohort of codebreakers and engineers.

Towards the end of our visit we found ourselves in Hut 8. Although the hut is home to Alan Turing’s office, it wasn’t that which had gripped my attention as much as the captivating display set up by the Royal Pigeon Racing Association.

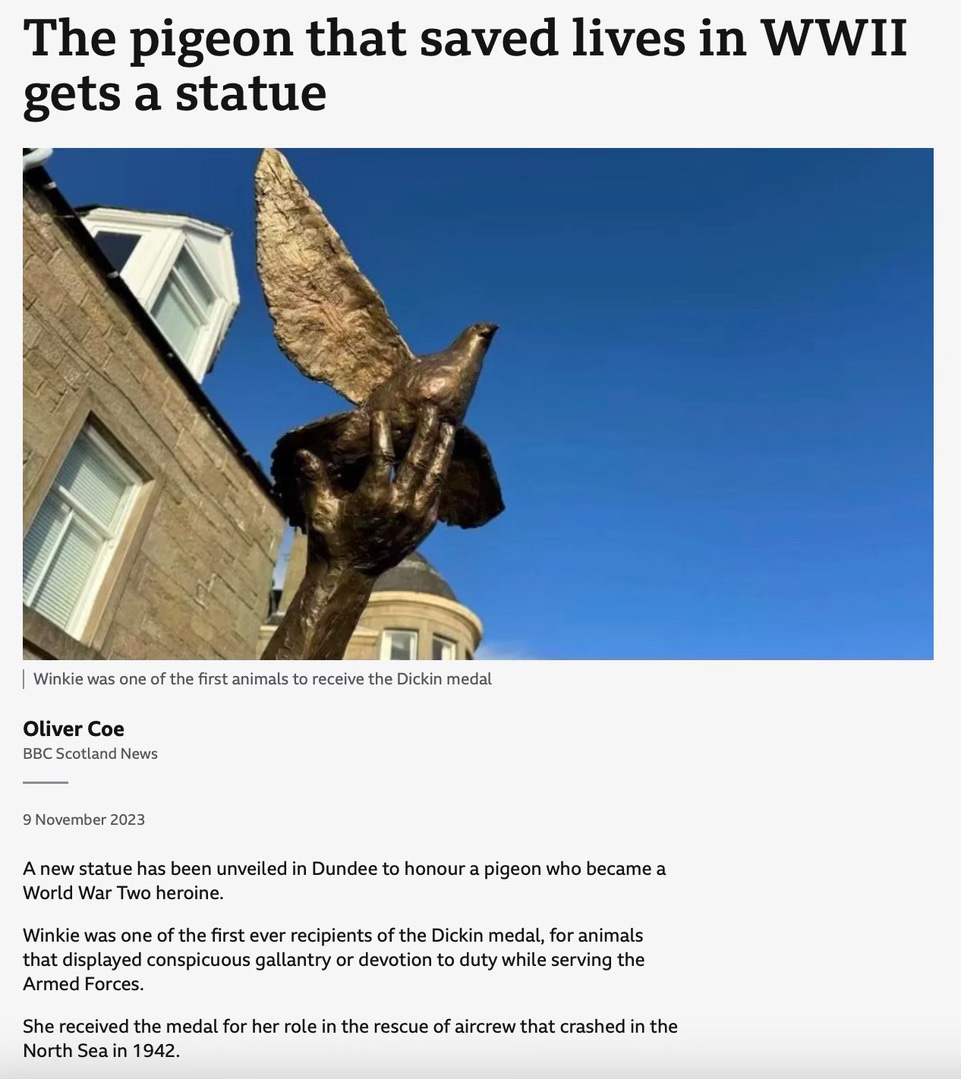

It was here that I encountered stories of such feathered war heroes as William of Orange, Duke of Normandy, Mary of Exeter, GI Joe and Winkie, all recipients of Britain’s highest award for animal valour, the Dickin Medal.3

The use of pigeons in times of war has a long history. By the end of WWI Britain had 20,000 pigeons in military use, with 400 dedicated handlers. Once the war was over, the German military kept their pigeons throughout the 1920s and 30s, recognising their potential value in future conflict, and in 1934 the carrier pigeon was even granted official protection by the German government. In contrast, the Allies had felt at the end of the Great War that their pigeons were no longer needed, feeling instead that modern wireless technology superseded any military assistance which pigeons could provide.

This feeling would not last, and in 1939 the National Pigeon Service was established. The organisation was initially modest, with pigeons at first only intended to be used as a distress signal from downed aircraft. Political leaders at the time had seen no value in the service, and as a result the National Pigeon Service was underfunded in favour of spending on wireless technology.

However, Winkie was one pigeon who helped to change forever the way that these birds would be regarded as tools of warfare.

With the RAF requiring two pigeons to accompany every bombing mission, Winkie found herself on board a Beaufort aircraft which crashed into the North Sea after a failed sortie near Norway on February 23, 1942. The crew had survived and sent an SOS, but the impact had destroyed radio equipment, and there was no other form of two-way contact available. Their only hope was in the shape of pigeon Winkie, who set off from the downed aircraft on a 120-mile journey to the Scottish coast. The search area for the aircraft had been immense, with the crew at base unable to narrow it down, but as soon as Winkie arrived, exhausted, calculations were made in order to establish where her starting point would have been. Based on the time that had elapsed between receipt of the SOS signal from the aircraft and the arrival of Winkie, rescue headquarters were able to narrow the search area, and within a very short space of time the crew were rescued.

In a corner of the Hut 8 exhibition space a video about the navigational gifts of the humble pigeon was running, and I sat down to watch.

In it, Dr Tim Guilford from Oxford University described how pigeons can find their way home even once released somewhere they’ve never been to or seen before. He recounted how recent tracking technology had produced a GPS unit small enough to be put on a pigeon and offering live second-by-second accuracy, and in a study some unexpected results were found: similar, in fact, to the findings of the honeybee research.

To scientists’ surprise – because flying is such a high-energy pursuit – it was discovered that the birds don’t fly in a straight line; instead, they take a very indirect route. You see, although pigeons are free in flight to go where they like, like those bees they use land-based features for guidance.

Never mind reducing mileage by going – with apologies to their corvid cousins – ‘as the crow flies’, the memorised mental map of a pigeon is made up of such land-based features as roads and mountains. ‘Sometimes’, the narrator of the video explained, ‘you’ll see them fly above a road to a roundabout, then take the third exit off to the right…’.

And pigeon racers have noticed the same: for instance, after releasing their birds they might watch them flying along the M5 motorway or the Severn estuary.

Now, I don’t have the benefit of an aerial view of my route when I’m walking it, and in fact the problems I have understanding a map are because I can’t apply that bird’s eye view to my real-life perception of the landscape on the ground. The two are irreconcilable; I find it impossible to relate one to the other.

Yet given that I am often walking on – or alongside – examples of dominant linear landscape elements ‘such as water channels, roads and field edges’ shown in the study to be what guide bees through their territory, surely I should be able to find my way easily from A to B?

Reader, I wish.

What I had assumed would be a straight-line, stress-free, ‘even-you-can-navigate-this-path-Rebecca’ route on a solo walk last year had been anything but those things. Despite my feet being located firmly on a ‘dominant linear landscape element’, the trail had the last laugh as soon as it hit suburbia. Here’s what I wrote about it in this post last summer:

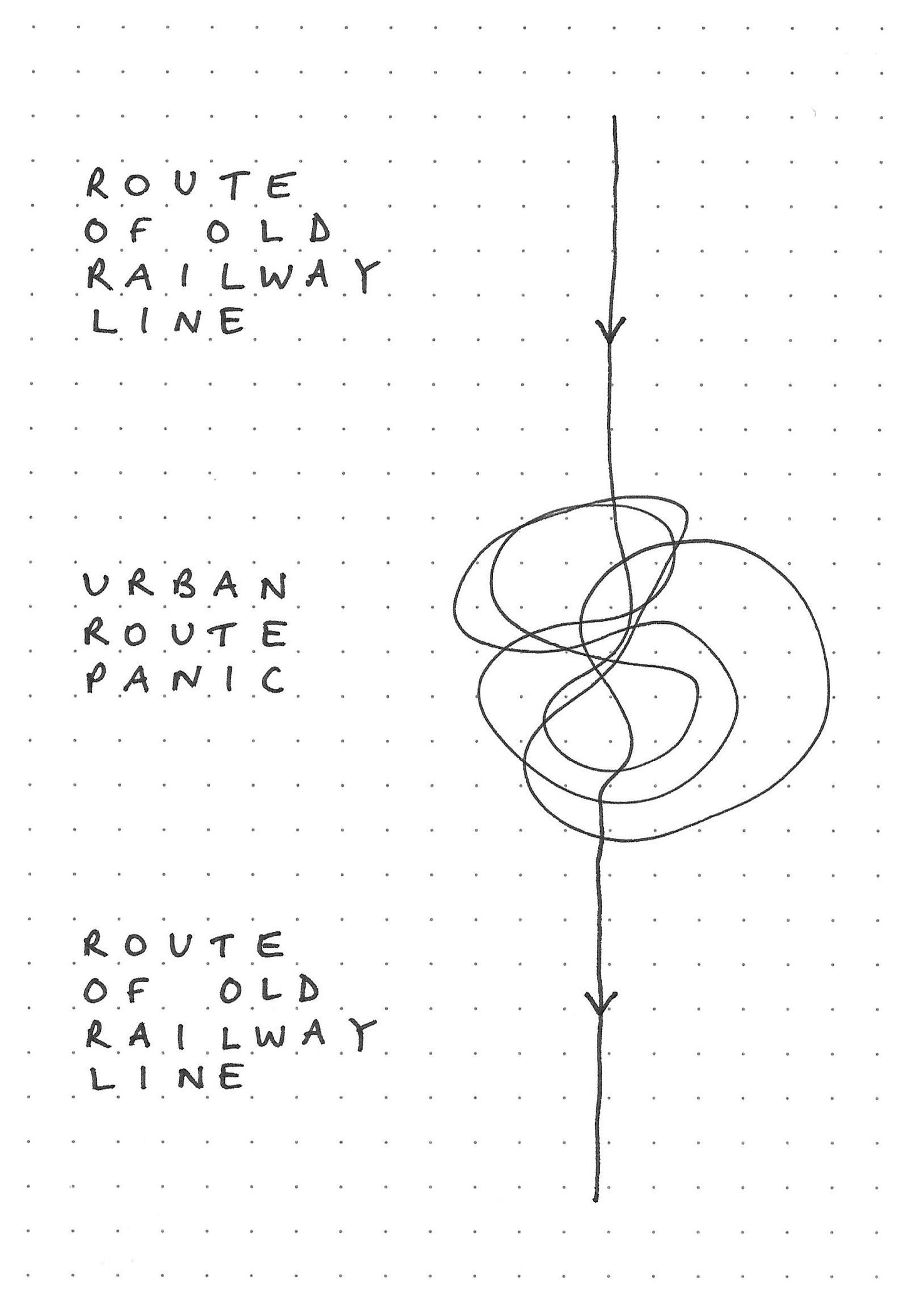

I’d decided to tackle a straightforward route. Fairly local to me is the ‘Cuckoo Trail’, a picturesque fourteen-mile trail comprising a surfaced path through the East Sussex countryside which follows the former ‘Cuckoo Line’ railway track between Heathfield and Eastbourne. Easy, right?

Well, yes, the parts of the trail which trace the route of the former railway that led across the countryside are straightforward to follow. Lined with patches of glorious woodland, it’s straight on all the way through former railway cuttings and atop a succession of embankments, and in places it runs alongside arable fields and cattle pasture.

On my walk, it was when the old railway line hit the towns that its route and I became entangled.

My most challenging part of the Cuckoo Trail had been to follow its route in the more urban areas such as the streets and twittens of Hailsham. This was where straight-line disused railway gave way to too many options: suddenly there were lanes and streets heading left and right, all distractingly planted to confuse this baffled walker.

Okay, I’ll say it: Reader, I’m a straight-line girl. My arrow follows one trajectory, and I am baffled by additional options, decision-making and any diversions along the way. Point me in the right direction and I’ll head off in it, absolutely, but please don’t give me choices. And if I ask for directions, please prescribe the precise route.

You’ve met my inner compass before, haven’t you? 🤣

A couple of years ago I was given a compass and a book entitled Navigation Skills for Walkers: Map Reader, Compass and GPS. Despite my best intentions, my sense of navigational daunt had overwhelmed me on my first read of the latter by the time I’d reached page 32 of 96.4

Here’s how the section on the compass begins:

There is nothing mystical about a compass.

🙄

And, a little later – after a difficult series of paragraphs detailing the difficult stages involved in the difficult learning process of how to use such a difficult piece of equipment – this:

There is nothing difficult about reading and using a compass, so do not persuade yourself otherwise.

🤯

The author went on to describe some of the factors that might adversely affect the functioning of this apparatus.

Because a compass relies on magnetism, many things, including your own personal magnetism, can affect the way the compass works. The usual culprits are cameras around your neck, mobile phone in your breast pocket, metal zips, and even the underwiring in a bra…

Ah, this looked familiar! Last summer I had learned in the amused yet tactful company of my lovely navigation coach Allan that there are certain Rebecca factors which can render such equipment useless:

Trying to use my compass while it was not only hanging vertically from my rucksack strap but also facing away from me;

Resting the compass against the top rail of a metal farm gate in order to view it ‘properly’;

Attempting to get a reading while standing between two National Grid pylons supporting multiple overhead high-voltage power cables.

The book goes on to recommend the following:

Trust your compass, not your intuition.

Okay, fine, I’ll read the book. 🙄

Intuition, though: isn’t that what the birds and the bees use? Pigeons, after all, were described by Dr Tim Guilford as ‘one of the most significant navigators in the animal kingdom’.

Like the honeybees and their ‘dominant linear landscape elements’, pigeons choose linear landmarks such as rivers and – yes – the M5 motorway, in that memorable snippet from the video I watched at Bletchley Park, but due to their flying position above the landscape the chaotic layouts of suburbia don’t distract them from their journey.

It’s not only the landscape that plays a part, though. For both birds and bees a number of different elements come together to create proficiency in navigation. Can these winged messengers rely on their own inner compass built, like my compass nemesis, around a magnet?

The narrator of the Bletchley Park video had explained that a powerful tool in a pigeon’s navigational armoury is its ability to pick up on magnetic fields. With linear landmarks so obviously lacking in the North Sea, I can only assume that Dickon Medal laureate Winkie’s magnetic radar had been what had got her home.

And how does that work?

University of Melbourne researcher, physicist David Simpson, revealed the following in an article from November 2021:

We know pigeons use visual cues and can navigate based on landmarks along known travel routes. We also know they have a magnetic sense called “magnetoreception” which lets them navigate using Earth’s magnetic field.

The current hypotheses

Scientists have spent decades exploring the possible mechanisms for magnetoreception. There are currently two mainstream theories.

The first is a vision-based “free-radical pair” model. Homing pigeons and other migratory birds have proteins in the retina of their eyes called “cryptochromes”. These produce an electrical signal that varies depending on the strength of the local magnetic field.

This could potentially allow the birds to “see” Earth’s magnetic field, although scientists have yet to confirm this theory.

The second proposal for how homing pigeons navigate is based on lumps of magnetic material inside them, which may provide them with a magnetic particle-based directional compass.

We know magnetic particles are found in nature, in a group of bacteria called magnetotactic bacteria. These bacteria produce magnetic particles and orient themselves along the Earth’s magnetic field lines.

Scientists are now looking for magnetic particles in a range of species. Potential candidates were found in the upper beak of homing pigeons more than a decade ago, but subsequent work indicated these particles were related to iron storage and not magnetic sensing.

Taken from How do pigeons find their way home? by David Simpson.

Well, it seems the jury’s out – although I rather think that that same jury would probably have some comment to make about the ‘lumps of… material’ in my head which render my own sense of direction entirely absent.

I’ll leave you with this picture of a smart alec I had met at the seaside.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have two thirds of Navigation Skills For Walkers left to read.

Reader, I’ll be a while.

Love,

Rebecca

📚 Reading 📚

📚 The latest edition of

is exactly what I needed to read this week; this wonderful post by is a fascinating history of the daily planner. My own planner of choice is a plain notebook, but I’m fascinated to have learned about some of the other options that people have used in times gone by.Read all about them here:

📚 Do you keep a journal? Do you start a new one every January? I use a blank notebook for all my journalling and planning, and for fear of waste I simply start a new one when my latest is full, in whichever month that may fall. The preference of

from the fabulous is to use a single book for an entire year from start to finish of both the year and the notebook. Now that is excellent planning! What do you think?You can read his post about it here:

📚 Regular readers of ‘Dear Reader, I’m Lost' will be no strangers to my ongoing light-hearted correspondence with fellow Brit

of Eclecticism: Reflections on literature and life. It’s my turn to write to him on Wednesday!If you’ve enjoyed this post, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

The original research article Generalisation of navigation memory in honeybees can be found on Frontiers.

Frontiers is an award-winning open science platform and leading open access scholarly publisher. Its mission is to make research results openly available to the world, thereby accelerating scientific and technological innovation, societal progress and economic growth. It empowers scientists with innovative open science solutions that radically improve how science is published, evaluated and disseminated to researchers, innovators and the public. Access to research results and data is open, free and customised online, thereby enabling rapid solutions to the critical challenges we face as humanity.

No, I didn’t get lost! 🙄

The PDSA Dickin Medal was instituted in 1943 in the United Kingdom by Maria Dickin to honour the work of animals in World War II. It is a bronze medallion, bearing the words "For Gallantry" and "We Also Serve" within a laurel wreath, carried on a ribbon of striped green, dark brown, and pale blue. It is awarded to animals that have displayed "conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving or associated with any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence Units". The award is commonly referred to as "the animals' Victoria Cross”.

Between 1943 and 1949 the medal was awarded to three horses, eighteen dogs and thirty-two pigeons.

Taken from Wikipedia.

The fact that this amounts to precisely a third of the book’s content fits beautifully my desire for order. Straight lines, see? I know I’d only got that far on my first reading of the book, because that’s where I found my bookmark.

Well for a start, if I was going to use a compass, I'd have to burn my bra!

And what about metal tooth-fillings from the old days or a false limb? How did Captain Hook do it?

Goodness - maybe it's better to just move in highly familiar areas so that one fits the brief for 'all those who wander are not lost.' Or words from Tolkein to that effect...

Once I went for a walk in Kathmandu and was so exhilarated by the people and the neighborhoods and the sheer exoticity (is that even a word? It should be!) of it all that my own brain lumps became hopelessly confused. Then I remembered the iPhone in my pocket, pulled it out for a look at my maps app, and found a moving blue dot that located me in the urban tangle. It guided me through the city streets and alleys toward “home.” But what a thrilling moment of realizing that I’d run off leash and found a whole new landscape to explore. Time to stop and savor the momos.