Dear Reader,

Every autumn, before the Liquidambar styraciflua1 that dominates our garden has even begun to paint new purple edges and speckles on its leaves, the Parthenocissus quinquefolia2 sprawling across the front wall of our house turns a pale yellow, then pink. Soon it’s a blazing red, and suddenly the wall is naked as the leaflets making up the creeper’s compound leaves flutter singly to the ground to make a scarlet drift.

I’m the odd one out in a family of horticulturists: my fingers are grubby, not green.

Houseplants die under my care. In my raised bed vegetable plants shrivel and die, bolt and die, get mildew and die, or just die. I wish it weren’t so, but I am not a natural nurturer. Let’s just be grateful that I don’t have any children.

I love being out in nature. I love the beauty of plants. I enjoy looking at them, touching them, breathing in the scent of their flowers and feeling the texture of their leaves. I enjoy eating them, too.

Yet the gift of growing them has passed me by.

The scale of my horticultural ineptitude, though, is at least equalled by the size of my passion for language, and I love the sound and feel of plants’ Latin names as I say them out loud.

I gather an early word in my vocabulary back when I was still ‘talking scribble’ (a term coined by my dad for my childish babbling) was ‘mesembryanthemum’.

Try saying that out loud. Mesembryanthemum.

muh-zem-bree-YANTH-uh-mum

What a glorious word! Reader, until sitting down to write this post I had no recollection as to what these floral treasures of my verbal childhood even look like, but here goes:

I’m not at all surprised that something like this would have been around in our garden in the mid-1970s: those heady days of feature rockeries and crazy paving. Heck, back then we even had a bamboo glade and some pampas grass.

So what had got me thinking about this? Out on my first local walk for what had seemed like weeks, I got lost on a route that I was sure I’d known like the back of my hand the last time I’d been on it. The path was suddenly unfamiliar, its edges blurred by autumn leaf fall.

Seeking comfort and reassurance from a known way I took a footpath route which runs through a beautiful private garden. It had been a while since I’d seen it, before even the first tinge of gold had hit the bracken.

And there in the late morning October sunshine I found that my favourite tree in the world – not for its appearance but for its name – had become a stunning, burnished copper.

Metasequoia glyptostroboides3

METTUH-sih-KOY-uh GLIP-toe-struh-BOY-deez

My parents have a passion for plants, gardens and gardening: their own garden is not something I can quite find words good enough to describe. Trust me, it’s beautiful.

Their parents, too, loved gardening. Grandpa’s greenhouse was his life’s work: in it, on a steep fellside in the cool northwest of England, he grew nectarines, two varieties of peaches and lustrous blacker-than-black grapes with a gorgeous fuzzy-looking coat of blue-grey bloom. I remember rubbing the bloom off a grape with my child-size thumb and being awed by the smooth, shiny black jewel beneath. Grandpa would use a rabbit’s paw to pollinate the peaches, which I would find fascinating. I never found out where he’d acquired the paw: I didn’t dare ask.

Grandma – no fan of the rabbit’s paw, and with a firm preference for Grandpa to pollinate with a paintbrush – would give us a tour of the garden on every visit. The switchbacks of lawn that snaked their way down the slope towards the lake would be lined with snowdrops, grape hyacinths or pinks, depending on the season, and her ancient acer was a source of particular pride. There were other trees, too. ‘That’s the oak that grew from the acorn you’d brought back from Brock Hole!’ she would tell me every year. I wonder how tall that tree is now, or even if it’s still there?

On Dad’s side of the family Granny’s garden was more utilitarian, with priority given to vegetables. She took care of all the natural life that stalked her crops, happily sharing her prolific brassicas with a large population of cabbage white butterflies. Mum still tells a good story about the first meal that Granny had ever cooked for her. ‘Cauliflower cheese, complete with caterpillars. I couldn’t eat it.’

Long pause.

‘But DADDY did!’

Poor Dad. I’m not surprised, though. He doesn’t seem to mind finding a slug in his homegrown salad either, although I’ve never seen him actually eat one.

Jars of delicious jams, jellies, chutneys and pickles would find their way from Granny’s larder to ours in varying quantities according to the size of the season’s yield. She was particularly keen on mint jelly for serving with lamb, and she’d make pounds and pounds of it. Raising sheep on our own smallholding we’d eat a lot of lamb, so mint jelly was always welcome.

Granny would chop the mint finely and boil it up with the endless supply of wonky cooking apples from the trees at the top of her garden to make a clear, deep rose-coloured jelly.

One Sunday lunchtime a new jar was brought out to the table, displaying a perfect earwig in the very centre: jellied forever in suspended animation.

Many of the plants in my parents’ garden are named after the place they were found or bought, or the people from whom they’d been a gift. Not all of the things growing arrived in ready-to-go plant format: it has been known for seeds, fruits or even a tiny sprig of something to grow on as a cutting to find its way into the greenhouse or potting shed, and eventually a plant pot or border.

🌱 ‘Mollie’s rose’ grew from a cutting from Grandma Mollie.

🌱 ‘Roy Lancaster’ – Leptospermum lanigerum4 – was grown at Kew from seed which Roy had collected in 1988 at Baker’s beach in northern Tasmania.

🌱 The oak by the pond is ‘Sam’s tree’, named after the gifted arboriculturist whose repeated attentions ensure that both its stately beauty and structural integrity are preserved.

🌱 ‘Highgrove’ is named after the former Prince of Wales’s country garden. Mum told me this:

It’s an acer we saw growing there. Charles5 had planted a group of them and we tracked one down at a nursery nearby.

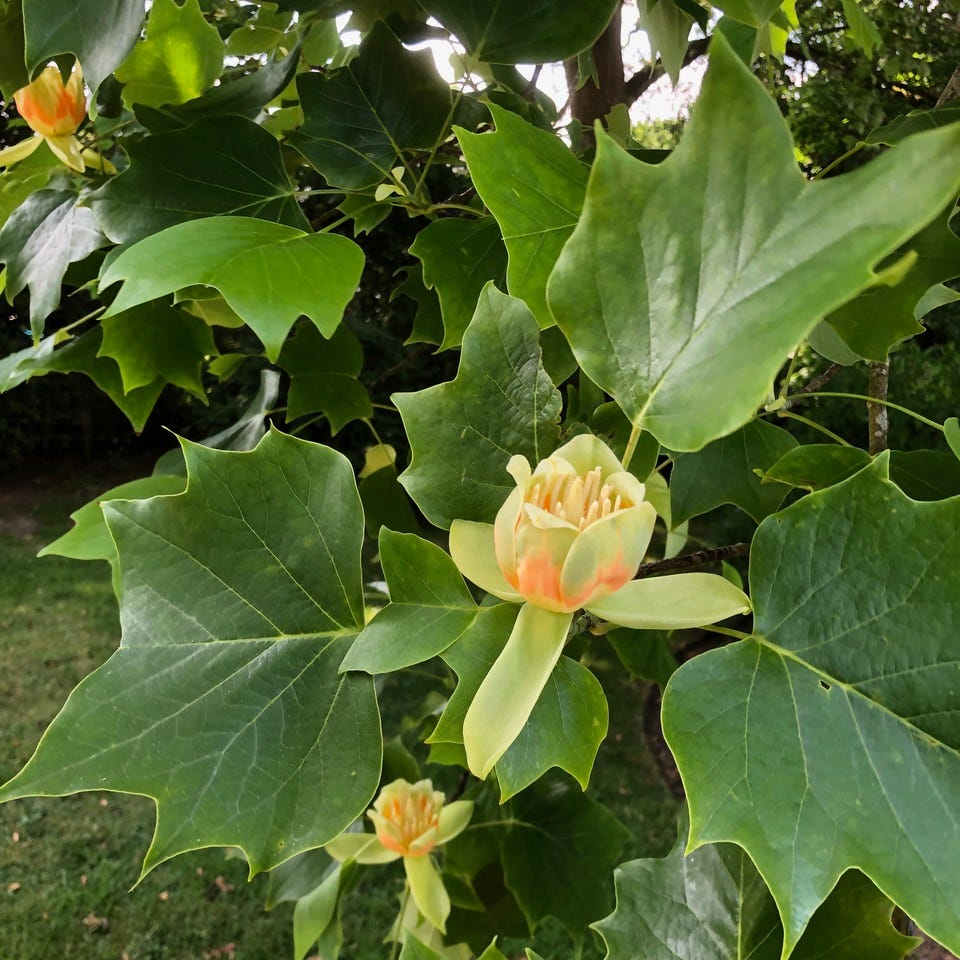

🌱 I’ve always called the Liriodendron tulipifera6 in the corner of their garden the ‘duck foot tree’, for a reason that I think is obvious:

On the day of my wedding, between the church service and the reception, my dad suddenly decided he wanted one of its flowers for his evening buttonhole. With none in immediate reach, he’d had to fetch a ladder with which to claim his prize. Mum had turned pale, while the bride remained blissfully unaware.

In binomial nomenclature, the Greek suffix -oides is adopted to show that the plant resembles something.

Our own latest acquisition for the front garden is a Trachelospermum jasminoides7, its bright white flowers appearing a close relation to the plant which its name tells us it resembles. This nominally-similar yet unrelated interloper is as sensually intoxicating as true jasmine itself.

So far, so sensible.

On a walk with Mum around a botanical garden one day we had stopped to admire an Indian bean tree – Catalpa bignonioides8 – in its summer glory; it had huge leaves and upright panicles of large, white flowers.

‘What are nonnies?’ I asked Mum.

She was puzzled. ‘Nonnies?’

‘Yes, nonnies. The label says this tree’s got big ones!’

Imagine my delight on another visit later in the year when the bean tree had come through with the promise on its label. Huge numbers of long, slender ‘beans’ were now dripping from its branches.

‘There you are!’ I announced. ‘Big nonnies!’ 🤣

Local English vernacular names can of course describe a plant’s appearance or behaviour, too.

To me a dandelion’s flowers have always resembled more a lion’s mane than its teeth, but in fact it’s the jagged-edged leaves which give their name to the plant known in French as ‘dent de lion’ – the tooth of a lion.

Jim had a long list of plants to photograph in his 18-month-long job shooting ‘Meadow: The intimate bond between people, place and plants’. The project was not without its challenges, as he explains in his words from the book:

“A futile search one long afternoon for meadow goat’s beard, Tragopogon pratensis9, left me scratching my head until the obvious – with hindsight – significance of its common name, ‘Jack-go-to-bed-at-noon’, finally dawned on me. A humbling lesson learned, and I made sure to return early the next morning to capture my subject.”

As for my own garden, it contains trees and anonymous shrubs, and a lawn whose shape I can’t describe, other than to say that cutting the grass is more of a challenge than I’d like. Snowdrops appear before spring is even on the radar, and right now my favourite autumn cyclamen are absolutely perfect. It is to Mother Nature’s credit that our little patch of land thrives in spite of my hapless attentions.

I’ll never be a horticulturist. The apples which I neglect to thin once fruit has set on our tree will not be jellied to anoint roast lamb or to preserve earwigs, nor am I likely to ever prune my hydrangea at quite the right time. But there are things I can do. I can watch for that first snowdrop in the new year, and sow runner beans in spring so that I can enjoy their later harvest. In summer I can cut the grass and try not to mind too much that the lawn is such a crazy shape, and in my October garden I kick my way through fallen leaves like a child instead of raking them up for the compost bin.

Reader, I don’t need to be an expert in plants to find them beautiful. And on my next walk in the autumn sunshine I’ll take time to bathe in the copper glow of the Metasequoia glyptostroboides as I repeat out loud its beautiful name.

Love,

Rebecca

📚 Recent reads 📚

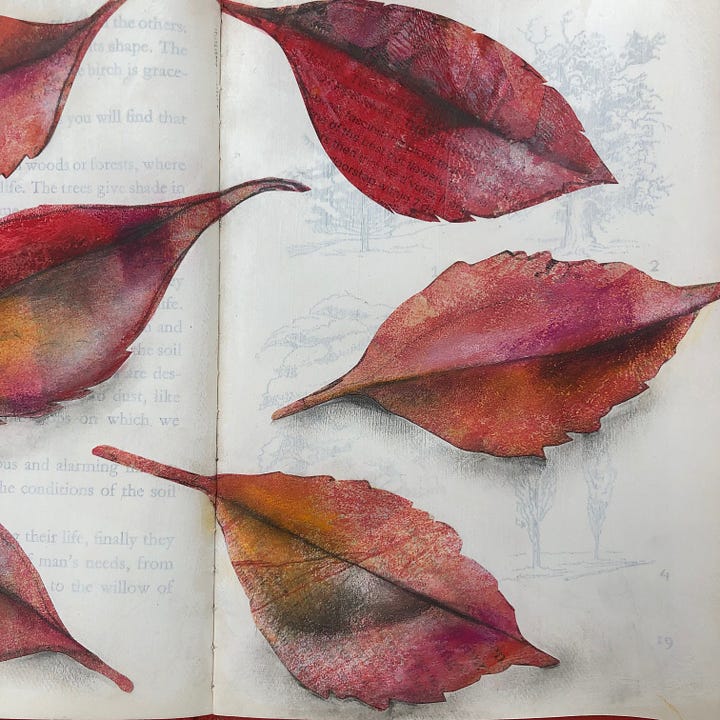

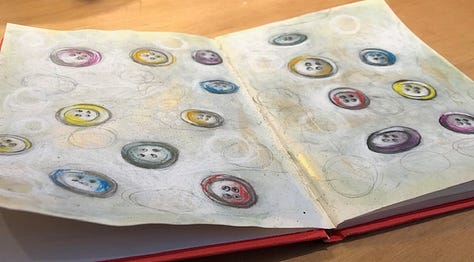

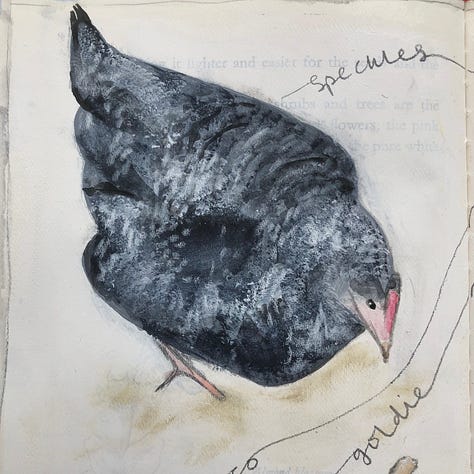

📚 Just a couple of days ago I came across freelance illustrator Melanie Chadwick on YouTube, and was thrilled to discover that she’s also on Substack! I’ve been wanting to develop more of an outdoor sketching habit, and Mel’s newsletter

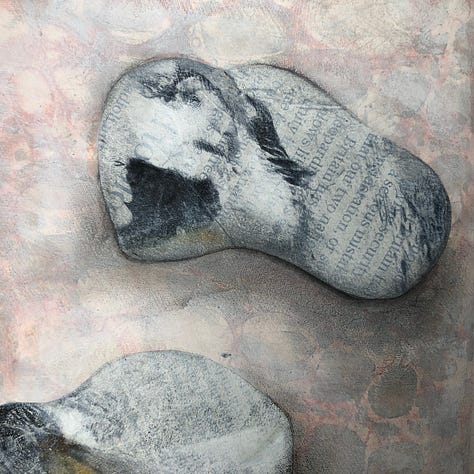

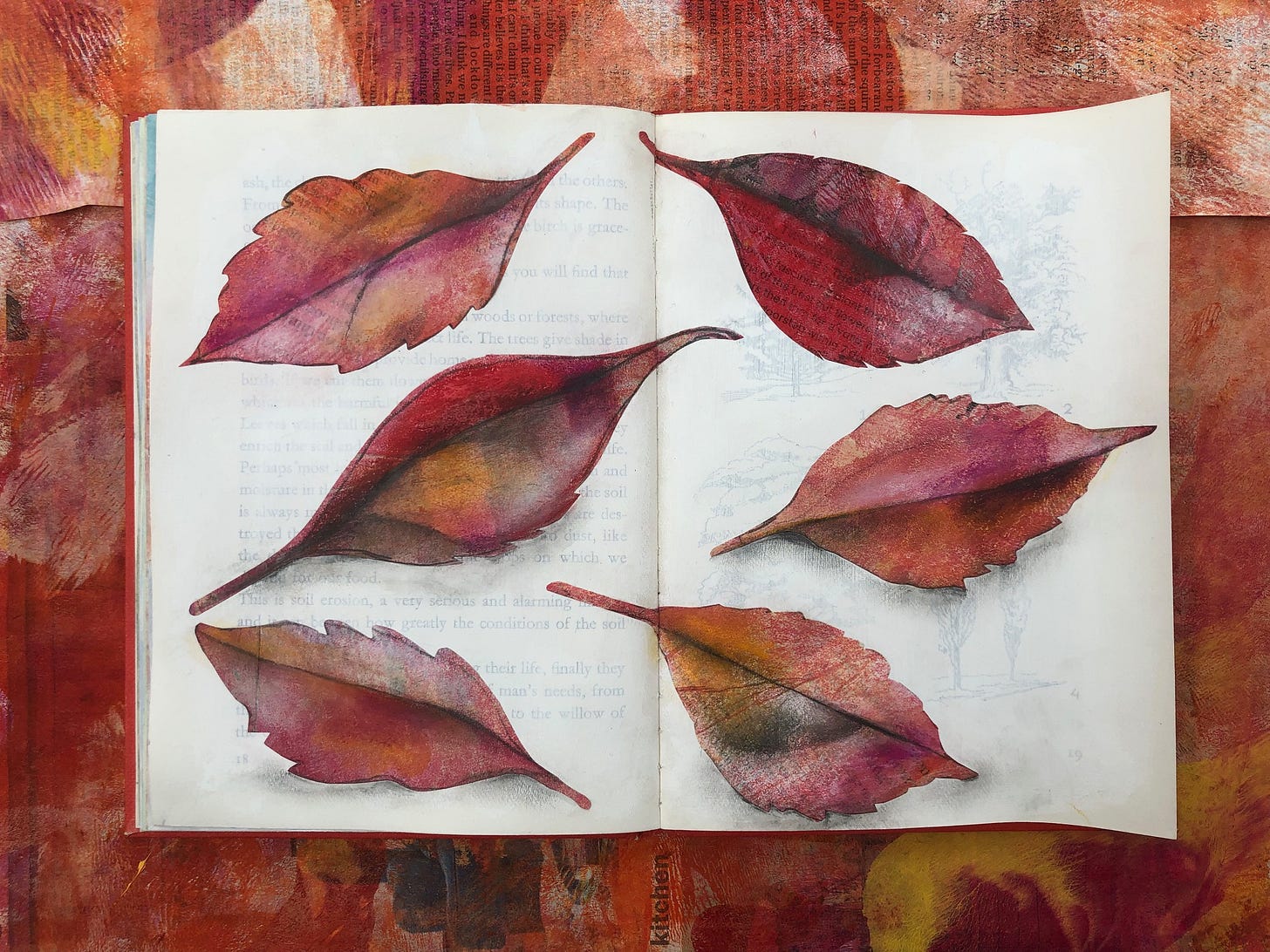

is already providing me with no end of inspiration to get out there! Here are her beautiful sketchbook pages from August:📚 Alison of

wrote this beautiful post last week about her apple-picking adventures:📚 I’m not the only Substack writer who feels that trees are poetry.

of ’s sonnet about the sweetgum (Liquidambar) is enchanting.📚 In this delightful post from around this time last year

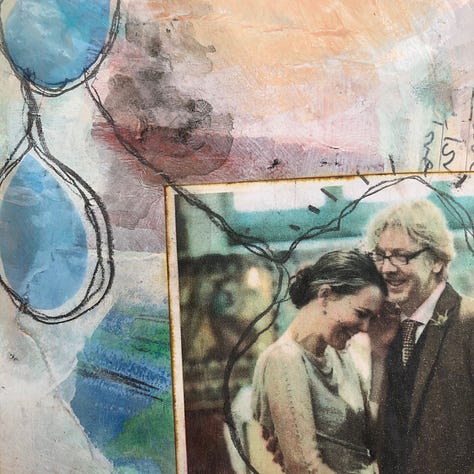

of took her readers on a tour, including a beautiful description of the two Catalpa bignonioides on her property.📚 Regular readers will be no strangers to my ongoing light-hearted correspondence with fellow Brit Terry Freedman of

. We met in person for the first time this month, and despite my having spilt coffee and showered frothy milk over Terry in two separate incidents, he has been kind enough so far not to sue me. It’s my turn to write to Terry on Wednesday, but in the meantime you can see all of our letters here.If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, the tenth in a monthly series exploring some of my memories in words and pictures, please let me know by clicking the heart. Thank you! You’ll find all the posts in this ‘Art & Treasures’ series here.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy ‘Dear Reader, I’m lost’, please share and subscribe for free.

‘Charles’?!

In case I have given you the impression that my parents are personal friends of the King, I’m afraid they’re not. The garden at Highgrove is open to the public.

Meadow goat’s beard - An erect annual or short-lived, tap-rooted perennial, with narrowly lance-shaped, long-pointed leaves and terminal dandelion-like yellow flowerheads which close about midday.

Golly, I would LOVE to walk through a garden with you so that you could describe things with big nonnies!

And thank you for the link to the Roy Lancaster teatree which comes from my own state. I went and read about it. I can't remember any Latin names at all and end up with David and Gavan's hydies over there, Willi's white flowered thing here and so forth and yet my friend Willi, who is the compleat plantswoman, rolls them off her tongue like a mouthful of marbles.

I rather fancy the Meadow book too. Jim's cover pic is EXACTLY what I would love to achieve in my small meadow patch behind the windbreak. So far, my experience with meadow plants has been in an ancient wheelbarrow.

I always enjoy your posts so much but the artbook days are my favourites. You are so talented, Rebecca. Thank you for sharing your creativity.

Gosh, so beautiful, Rebecca. I am captured by the pictures and have to return later to savor your prose. (And thanks for the pronunciation tips and the link!) Trees in Rougemont decided a couple days ago to let loose their leave, with the hickories taking the lead. Browns and yellows scattered all around. The Maple is stillred and full. She'll hang on for a while. The oaks a browning but they're in denial. Another 3 sonnets on a tree inmy 'stack this week, BTW. Wonderful fall to all!